The position of Jane Austen (1775-1817) in the literary pantheon is secure and has been for a long time. Nevertheless, there are still some very odd attitudes to her literary achievements and how they relate to her own life. It is true that she wrote works which are comedies, in the sense that they conform to the tradition of ending in a marriage, as opposed to tragedies, which traditionally end in death. This fact seems to encourage some readers (or perhaps film viewers) to regard her as “merely” a romance writer and to extrapolate from that to form judgements on her life as a single woman. They fix upon the few accounts that survive of what might have been love affairs, and they pity her for not having found a husband, a dire fate they attribute to factors such as the dearth of men in England because of the French wars, and her lack of a dowry.

But, as Duke Ellington memorably said in a 1958 interview, “if a painter wants to paint a picture of a murdered man he doesn’t have to be murdered.” Given the rate of death in childbirth at the time, this is not an entirely irrelevant example, but Austen was also well aware of the freedom she would surrender if she had married. It is possible that she would have been able to pursue her writing– of course some married women did have successful artistic careers– but it may also be the case that she made an active decision to stay single, making do on a small income in her household of congenial women. She was free to make her own decisions about how she spent her time.

And one of the ways she spent her time, alongside her writing, was making music. She did not ‘create’ music in the way that she created literary works. But she collected music, sometimes by purchasing printed scores and sometimes by copying the sheet music for songs and piano pieces into music manuscript books, or onto loose sheets of music manuscript paper. Some of this sheet music survives and thus we have evidence of the music she liked to sing and play throughout her life, from her teenage years onwards.

More than 50 years after Austen’s death, her niece Caroline Austen remembered some songs her aunt used to sing at a time in her life “when she had nearly left off singing.” Caroline wrote, in 1870, that she thought her aunt played “very pretty tunes” but that the music would “now be thought disgracefully easy.” Caroline’s older sister, Anna Lefroy, said that “nobody could think more humbly of Aunt Jane’s music than she did herself.” Caroline also wrote that she “could not be induced to play in company,” which probably means that she only played at home for close family. Nevertheless, she continued to practice the piano every morning before breakfast.

It seems, then, that Austen’s musical practice was important to her not as a social asset but as a personal resource. She may have occasionally played country dances for her young relatives, but to spend an hour each day alone with one’s piano and one’s music collection without a performance in prospect implies that the ‘practice’ of making music is important in itself. At the very least, it must have been something she found enjoyable, and perhaps fulfilling. I believe, also, that the embodied practice of music stayed with her when she was writing her musical and expressive prose.

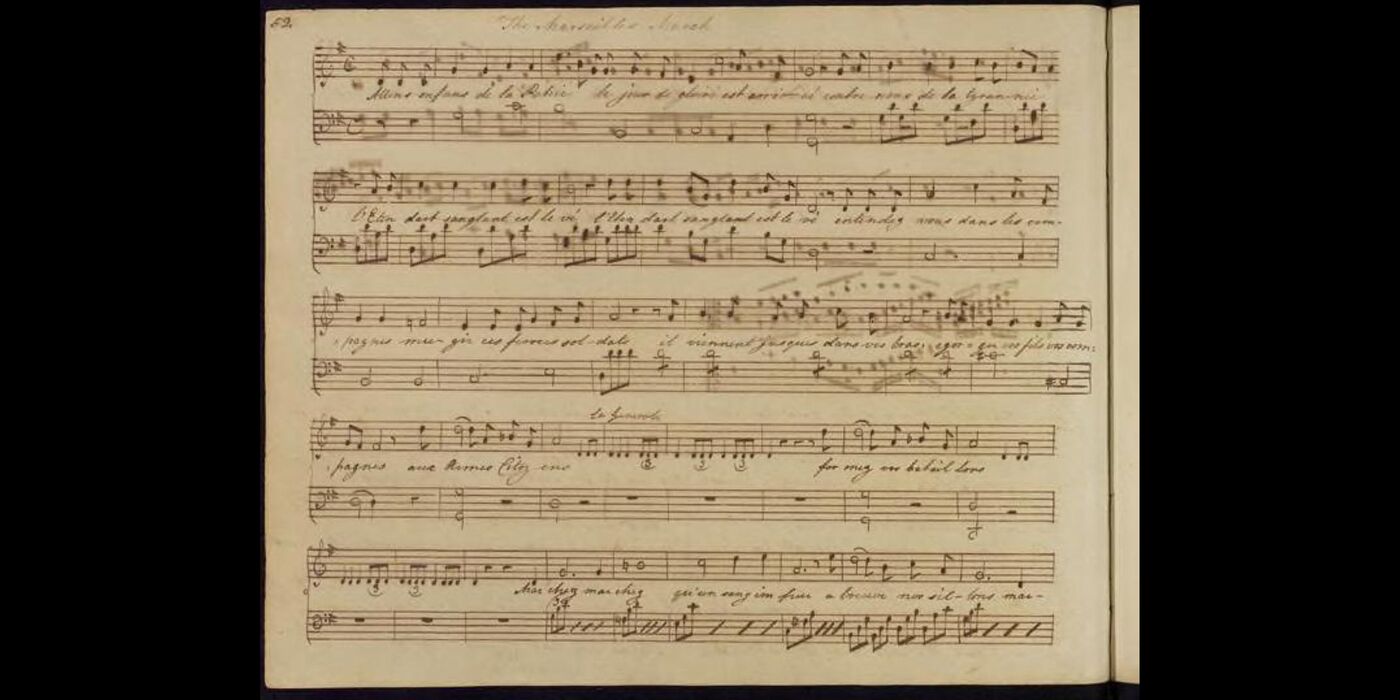

Her surviving music collection, which contains hundreds of songs and piano pieces, is also a useful addition to the information we have about her interests and attitudes, Indicating, for example, a more informed interest in political events than she is often given credit for: there are several songs relating to the French Revolution in one of her early manuscript books.

Some music scholars, however, have examined the Austen music collection, as well as her novels and her letters, with a critical eye. Based on passing remarks, often taken out of context, they sometimes express negative judgments about Austen’s musical taste and that of her contemporaries.

Even her niece Caroline’s remark about the music being ‘disgracefully easy’ seems to be a value judgment based on the differences between the more complex musical styles current during her own adulthood, rather than a dispassionate reflection on her aunt’s musical taste. The attitudes reflected in many modern commentaries seem to follow suit. The music that Austen played is, in the main, repertoire from the last quarter of the eighteenth century, a time during which amateur music making was increasingly popular.

The development of the piano was to some extent driven by the popularity of the instrument among women in a domestic setting. A large amount of music was written for this market: sonatas, variations on pre-existing themes from folk music or opera, dances, and a range of ‘lessons’ and ‘studies.’ Much of this music, by composers such as Ignaz Pleyel (1757-1831), Muzio Clementi (1752-1832), and J.B. Cramer (1771-1858), though technically not so difficult, still has its own value and beauty. However, it is now overshadowed, in retrospect, by the more complex works of Mozart (1756-1791) and Beethoven (1770-1827); though Mozart was a generation older than Austen, his music was not well known to her.

But the fact that the music is technically easy– even “disgracefully easy” in Caroline’s opinion– does not seem to me to diminish the artistic and personal fulfillment that could be derived from playing it. And the songs, which range from sentimental love songs to nautical ballads, from pithy Scottish folk songs to French art songs, allowed her to inhabit a varied world of emotions and actions in personas that cross gender, class, and cultural boundaries to an extent which might surprise those who only know the world of her published novels.

Gillian Dooley is an Honorary Associate Professor in English literature at Flinders

University, South Australia. She has published widely on various literary and historical

topics. Her research on Jane Austen often focuses on music in her novels and her world, and as a singer she has been curating and presenting programs of music from Austen’s personal collection in Australia and overseas since 2007, often incorporating performance into her presentations. From 2017 to 2021 she created a detailed index of each of the hundreds of items in the Austen family music collections for the University of Southampton Library catalogue. Her book She Played and Sang: Jane Austen and Music will be published by Manchester University Press in 2024, and her Jane Austen’s music website includes lists of performances, presentations, and articles, as well as information on the Austen Family Music Books.