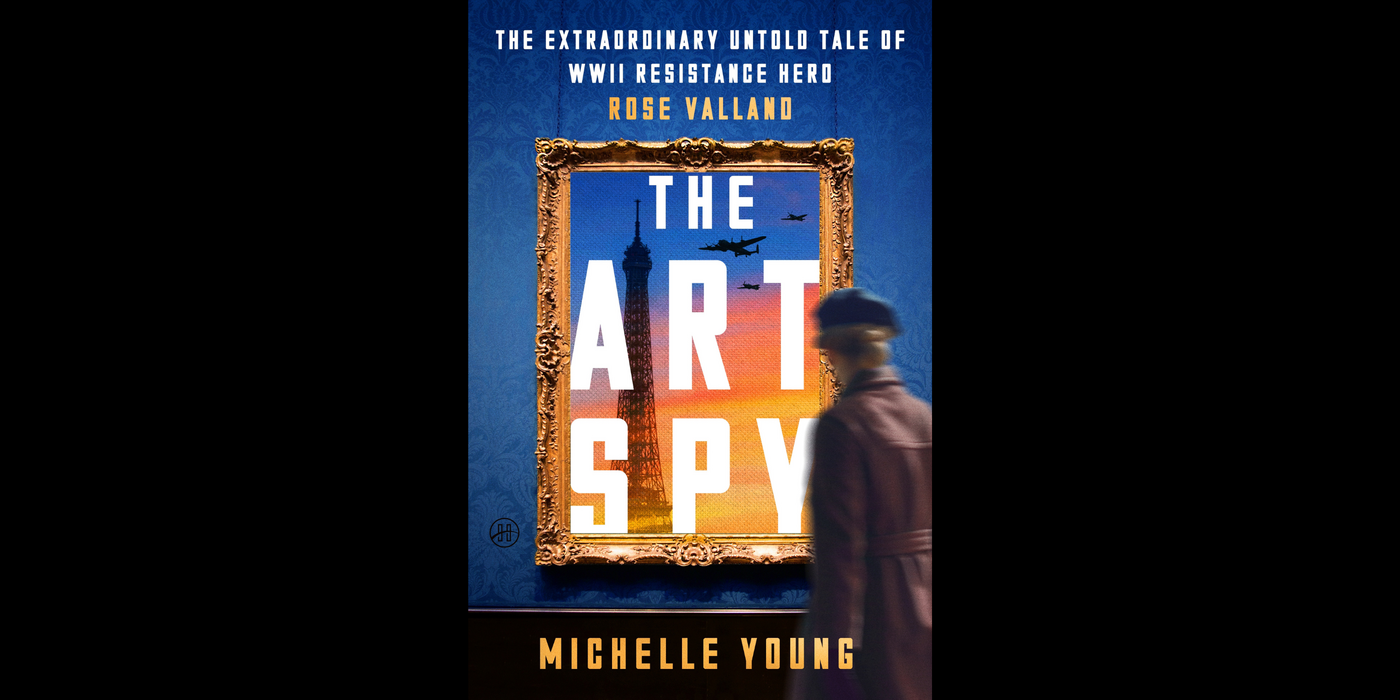

A riveting and stylish saga set in Paris during World War II, The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland uncovers how an unlikely heroine—Rose Valland—infiltrated the Nazi leadership to save the world's most treasured masterpieces. The excerpt below details Valland's introduction to the art that determined the course of her life.

PARIS

1939

The one thing Rose Valland loved most in the world was art. For as long as she could remember, she lived and breathed it. Life, as she painted it, was awash with bright pinks, reds, purples, and yellows. It was colorful and hopeful—a stark contrast to her somber childhood. This search for beauty, in all its forms, drove Rose in a singular, obsessive fashion. It was also her ticket out of Saint-Étienne-de-Saint-Geoirs, the isolated village she was born in, fifty miles southeast of Lyon.

Since the early days of the Holy Roman Empire, this area of eastern France was renowned for its religious martyrs and the piety of its people. The many fortified stone castles and citadels in town were a stark reminder of the religious wars that dominated this region during the Middle Ages.

There was an immutable harshness to the landscape and the climate, with cold, cloudy winters and hot, rainless summers. Locals toiled in the fields of the treeless open plain and worked in textile factories producing silk and other woven fabrics. In the distance stood the snowcapped Chartreuse Mountains, where silent Carthusian monks had produced a potent green liqueur—an “elixir of long life”—for nearly a thousand years.

Rose’s early years were not particularly joyful or beautiful. She came from a simple, working-class family of mechanics, wheelwrights, and blacksmiths, and her father worked the smithery attached to their modest stone house. From birth, Rose was surrounded by the harsh clanging of iron and a dark soot that hung in the air and stuck to everything.

She was surrounded by deep sorrow. Her older brother died as a toddler, rendering Rose an only child. Life at home was dominated by the hardy matriarchs of the family, while Rose’s father was mostly uninvolved in her life. When Rose wrote home as a young adult, she usually only addressed her mother. “Ma chère Maman,” the letters opened.

Rose was a sickly child and started school late, but she caught up quickly. Her mother was determined and formidable. She nurtured Rose’s early talents in academics and the arts and diligently applied for local scholarships. Rose’s own aptitude and persistence put her consistently at the top of every school she attended. As a precocious teenager, Rose was shipped off to an all-girls boarding school, and then, after placing first in a regional academic competition, she spent all of World War I on a scholarship studying at the Teachers College in Grenoble, an industrial city thirty miles from home. While writing a thesis on the pedagogy of drawing, Rose witnessed the transformation of Grenoble from a center of glove manufacturing into an armament hub where explosives, shells, and chemical weapons were fabricated for the war.

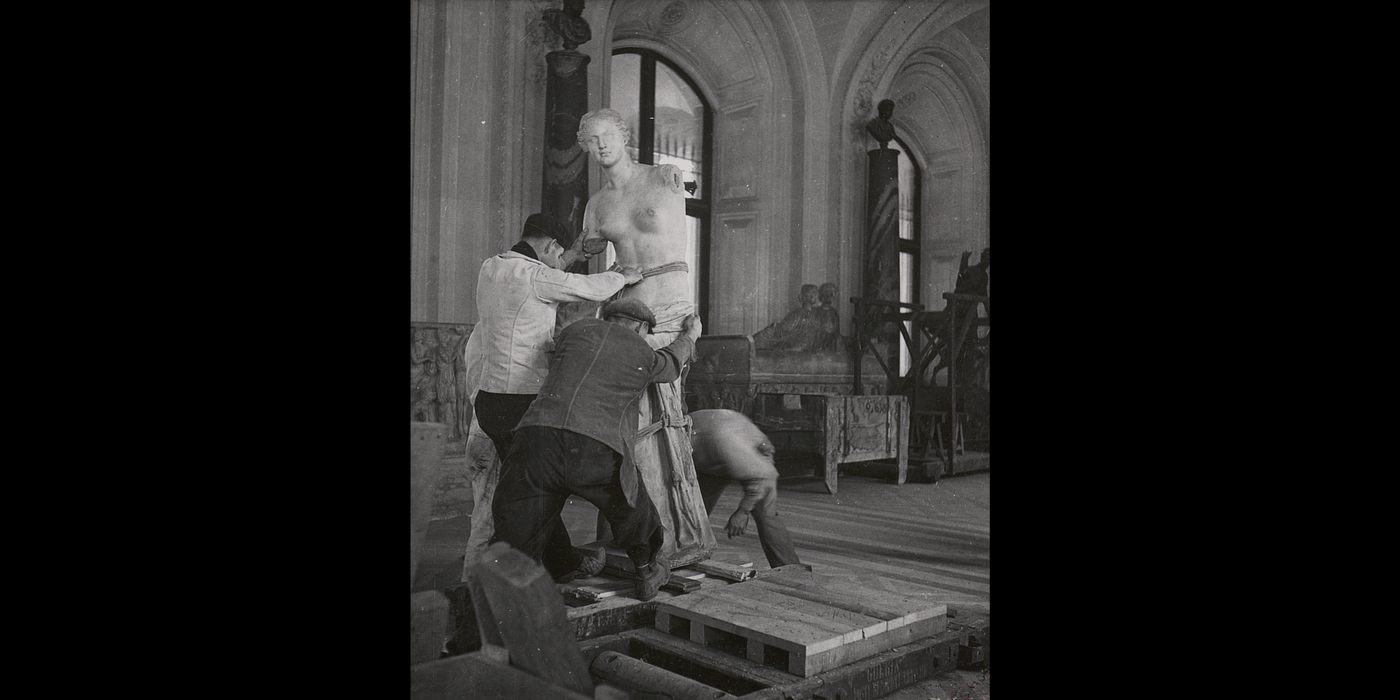

At twenty, considered a prime age to get married, Rose was accepted to the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, France’s third-largest city at the time with over half a million residents, where she won regional and national awards in art history and in the fine arts for painting, drawing, and decorative arts. She was then one of only a handful of women admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the prestigious art school where Eugène Delacroix, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Jean-Honoré Fragonard had all studied. The entrance exam took nearly forty hours and included live drawings of the human figure, anatomy, perspective, and architecture, as well as a test in art history. Out of three hundred candidates, Rose finished sixth, ensuring her a spot.

However, Rose soon learned that the school barred all the female students from the drawing workshop because of the use of nude male models. The women’s only class was full, and the school director refused to open another one, but Rose found a way into the drawing teacher’s studio anyway.

Rose’s degree from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris would qualify her to be an art teacher, but her interests soon expanded. She enrolled at the École du Louvre, a school that trained future curators, museum administrators, and art historians. These careers were traditionally only open to men, but the Great War had wrought dramatic changes in French society. Women like Rose came to Paris to attend university and to find work. The low cost of living and the collapsing franc attracted artists from all over the world who relocated to be amid the explosion in modernity.

Since the start of the twentieth century, women in France had gradually gained more rights, including the right to have their own salary, to maternity leave (albeit unpaid), to join a union without a husband’s consent, and to an equal education between the sexes in middle school and high school. But as Rose discovered, sexism still prevented women from getting hired for jobs they were more than qualified for.

In addition to her degree at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Rose also obtained a diploma in art history at the Sorbonne, combining certificates in Greek archaeology, medieval archaeology, and the history of modern art, and took supplementary courses in Byzantine archaeology at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, one of the best universities in France. She also took English language classes and went abroad for several months in England to improve her language skills. In all, Rose dedicated nine years of her life pursuing degrees in higher education.

But no matter how well Rose did academically or how far she was from home, she could never quite shed the severity of the world she had come from. It showed in the way she carried herself, her reserved demeanor, and her direct, masculine manner. She never quite fit in. Though she adopted a way of speaking in the lilting manner of the educated upper classes that belied her working-class origins, she lacked the social ease of the elite.

While Rose’s female classmates were chummy and physically affectionate with one other, Rose was an awkward loner. Her closeted attraction to women led her to treat them particularly harshly. Love evaded her.

Her internal life, however, was one of exuberance and full of modern ideas. “Isn’t movement the very expression of life?” she wrote in the opening of her dissertation at the École du Louvre. The introvert in Rose wanted to show that joy and life could emanate through art without words needing to be spoken. She wrote that when art closely imitates real human movement, it could make someone feel something close to the sublime, “an enjoyment that no words can make us feel, that music itself cannot give us.” Through the making and study of art, she could express a vivacity she dared not show in her personal life. She was a woman yearning to break free and to make her mark somehow.

From the book THE ART SPY: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland. Copyright 2025 by Michelle Young. Reprinted by permission of HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Michelle Young is an award-winning journalist, author, and professor whose writing and photography has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, Hyperallergic, The Forward, and Narratively. She is a graduate of Harvard College in the History of Art and Architecture and holds a master’s degree from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, where she is a Professor of Architecture. She is the founder of the publication Untapped New York. She divides her time between New York City, Paris, and the Berkshires, Massachusetts. Instagram @michelleyoungwriter, Threads @michelleyoungwriter, X @michelleyoungny, Bluesky @michelleyoung.bsky.social