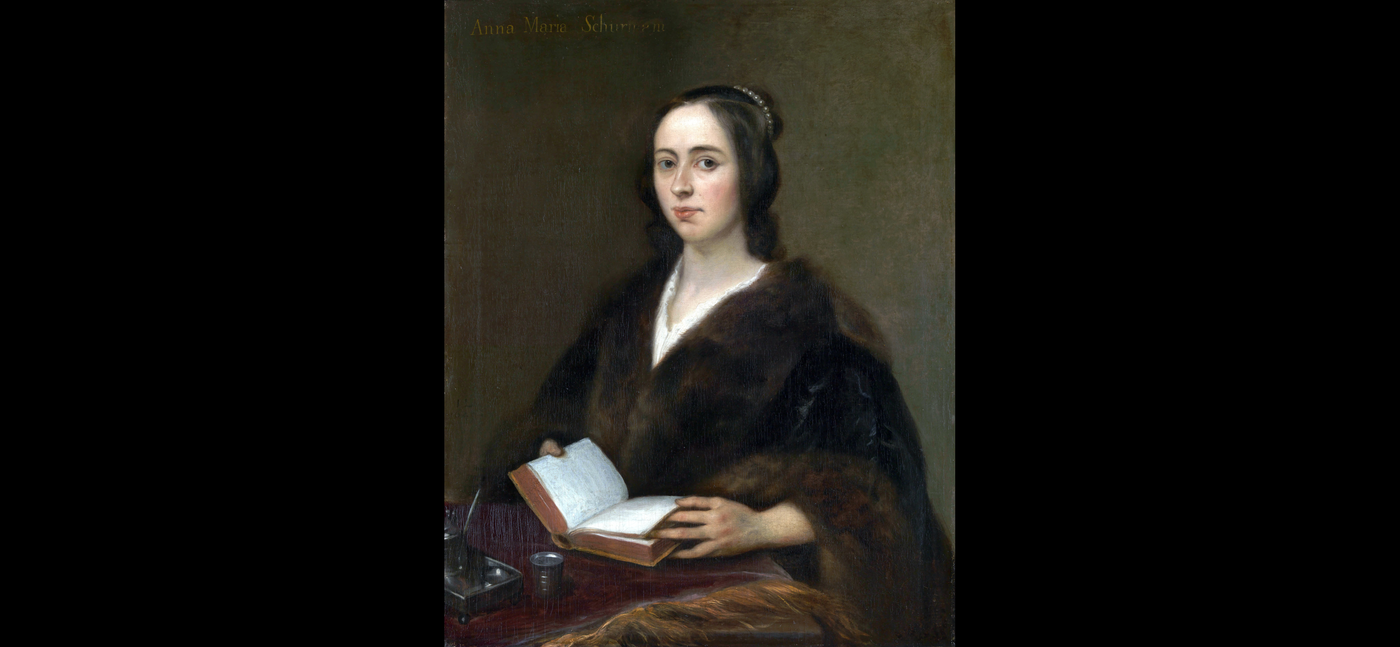

Throughout history and across different cultures, women have invoked female predecessors as a way of expressing a collective sense of solidarity between women and their past, from which they derived inspiration and authority for their aims and aspirations. A notable example is Christine de Pisan’s Livre de la Cité de dames [Book of the City of Ladies], which peoples her imagined city with some 165 female figures. Similarly, Bathsua Makin’s Essay To Revive the Antient Education of Gentlewomen impresses by the range and number of women she invokes, from “Zenobia Queen of Palmeria” to poets Sappho and Corinna, a long list of learned women, and several of her contemporaries: Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle; Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia; Queen Christina of Sweden; Anna Maria van Schurman; and her own pupils.

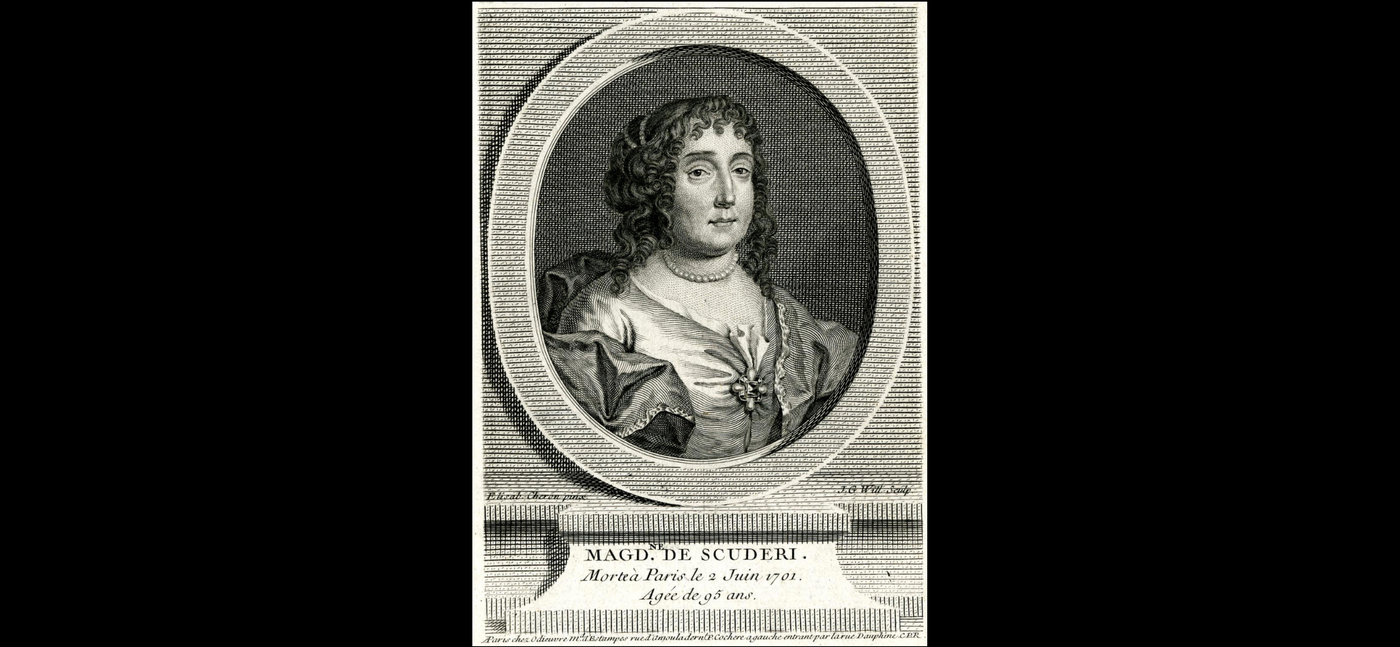

A woman’s choice of historical figures does, of course, reflect her purposes in invoking them. De Pisan and Makin emphasise their numbers to dispel assumptions that the paucity of women proved their insignificance. Often individual women cite those closest to their own aims and interests—for example, the Italian feminist humanist Lucrezia Marinella cites her humanist contemporary Moderata Fonte. The Italian Cartesian, Giuseppa-Eleonora Barbapiccola, acknowledges Marie le Jars de Gournay and Elisabeth of Bohemia as models for female philosophers. And Mary Wollstonecraft honours the historian and feminist Catharine Macaulay as an admired forebear. Others reach further back into antiquity: Marguerite Buffet, for instance, celebrates Madeleine de Scudéry by recourse to ancient precedent as ‘le Sappho de nos jours’ in her Les Eloges des Illustres Sçavantes, tant Anciennes que Modernes. Another important way in which women have valorised their past is by means of biography, a genre that develops especially after the advent of print, and the increase in female literacy and authorship which it sustained—e.g. Ann Thicknesse’s Sketches of the Lives and Writings of the Ladies of France (1780–1) and Mary Hays’s Female Biography (1803).

Initially, in Europe, accounts of historical women were mined from historical and religious sources authored by men, from classical sources such as Plutarch’s De Mulierum Virtutibus [On the Bravery of Women], moral exemplars to be found in legends of good women and saints’ lives, and even male-authored histories of women. Giovanni Boccaccio's De mulieribus claris [On Famous Women] was a major source for Christine de Pisan. Works designed to impress women patrons provide another source (for example, Gilles Ménage’s Historia mulierum philosopharum and Henry Cornelius Agrippa’s De nobilitate et praecellentia foeminei sexus [On the Nobility and Excellence of the Female Sex]), as do polemical writings (querelle des femmes). Ultimately the developing genre of female-authored biography furnished abundant material from which women could draw.

However, throughout history, there was no single, static biographical panorama of the past and no uniform model of women’s perception of past women.

Although we notice the recurrence of individual names (for example, both Bathsua Makin and Marguerite Buffet celebrate Queen Christina of Sweden and Anna Maria van Schurman), there was no fixed cast-list of figures, nor a single view of female historical actors or what they represented for those who invoked them. There are many reasons for this plurality—not least the fact that different figures were invoked in different ways at different times for different purposes. The plurality may also be explained in large part by the fragmentariness of women’s recorded history, and the educational disadvantages suffered by women in all societies which limited access to knowledge. It is no accident that dominant among the figures prized by later ages are educated women.

Since the pioneering work of female biographers like Mary Hays, the cumulative effect of biographies authored by women has been the enlargement and enrichment of the historical canvas of women’s lives. Championed by ‘New Women’ of the 19th century, historical biography was not a static mirror of the present but a dynamic shaper of both the present and women’s perception of their solidarity with women of the past, and it changed as women’s circumstances, priorities, and historical understanding changed. The past which women invoked in solidarity with contemporary concerns was a past reconstructed through the shifting prism of their present. The testimony of history to the existence of women thinkers, activists, mathematicians, writers, and rulers has provided not just inspiration for the philosophers, scientists, historians, poets, and political actors who invoked them, but a basis to argue for greater female access to education, for social justice, and for political equality. Thus, by testifying to and valorising the activities of women across time, female biography speaks to the concerns of feminists in different periods and places. However, the ongoing project of reconstructing women’s lives has its own limitations: the problem of sources, and lack of written records. The history of the majority of women is a history of the unlettered. The challenge for writing the unwritten lives of women is to develop methodologies for tapping the unlettered past.

Sarah Hutton is an honorary visiting professor at the University of York, UK. She studied at New Hall, Cambridge (one of only three Cambridge colleges that admitted women), and the Warburg Institute. She has published extensively on women in the history of science and philosophy. Her publications include Anne Conway: A Woman Philosopher, Elisabeth of Bohemia (1618–1680) (co-edited with Sabrina Ebbersmeyer), and articles on Margaret Cavendish, Damaris Masham, Mary Astell, Catharine Macaulay, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Émilie du Châtelet.