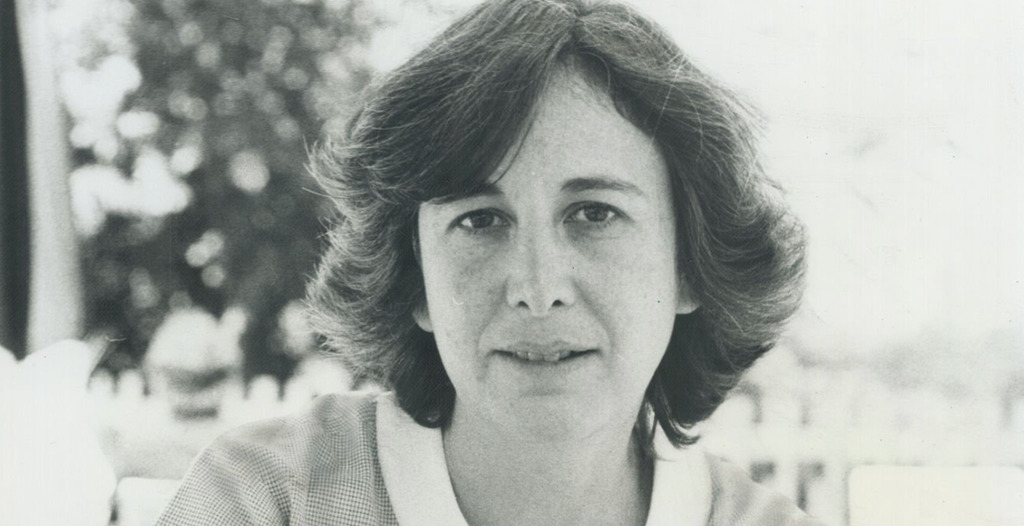

I was fully engaged in writing a biography of radical feminist Susan Brownmiller when the Texas Fetal Heartbeat law, which limits the right to an abortion to six weeks, went into effect on September 1, 2021. #MeToo activists had already persuaded me that Brownmiller, author of Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (1975), the first major historical and cultural account of sexual assault, was a neglected 20th-century intellectual.

But it was abortion that brought Brownmiller—a left-wing organizer, civil rights activist, and television newswoman—to the budding radical feminist movement in 1968. That movement, and her role as an organizer and writer, would redefine the 20th century.

I came to this biography circuitously. I had done several years of research toward a book on radical feminists who were central to the movement’s anti-violence projects in California, Boston, and New York City, a project that I put on hold to complete another book. After agreeing to an interview in 2009, Brownmiller had been instrumental in connecting me to the women I needed to talk to—but it was only later that I realized the significance of her support. She had been a central figure in driving radical feminist politics in the 1970s and 1980s, yet she had become a bit player in accounts of the movement.

Only a biography could explain why Brownmiller was so central, and the answer to that question was that Brownmiller was first, last, and always a media professional, part of a small cadre of women who invented feminist journalism. She became that person before she became a feminist, and long before it was possible for most women to have journalism careers.

Brownmiller’s life is also a quintessential New York story: the child of white-collar Jewish working parents, she had no material advantages and worked her way up from the bottom. A standout student at Brooklyn’s competitive Midwood High School, she won scholarships to attend Cornell, though not enough to support her for more than two years. There, she plunged into left politics, joining a group called Students for Peace that opposed the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the McCarthy purges, and nuclear proliferation.

By the mid-1950s, working in entry-level publishing jobs in Manhattan, Brownmiller became even more political. While many fled the left after 1956, she moved toward it, taking courses from Marxist historian Herbert Aptheker and joining groups like the Fair Play for Cuba Committee and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). By 1960 she was also working on Reform Democrat Mark Lane’s insurgent campaign for the New York State Legislature. She and Lane became lovers: although Brownmiller would never marry, embracing her own sexuality as a single woman, long before it was socially acceptable to do so, was part of her radicalism.

In 1963, she snagged a research job at Newsweek magazine, and the following year, took vacation time to go to Meridien, Mississippi, for Freedom Summer. That fall, she latched onto a television news crew in Jackson, Mississippi, writing and publishing her first piece of investigative journalism in the alternative New York weekly, The Village Voice.

Brownmiller continued to work as a network news writer and wrote freelance for the Voice, which launched the careers of numerous feminists, until the late 1960s. By 1969 her writing and activism fused when she joined New York Radical Women, one of the first radical feminist consciousness-raising groups in New York. The following year, her landmark feature in the New York Times introduced readers to what was now known as women’s liberation.

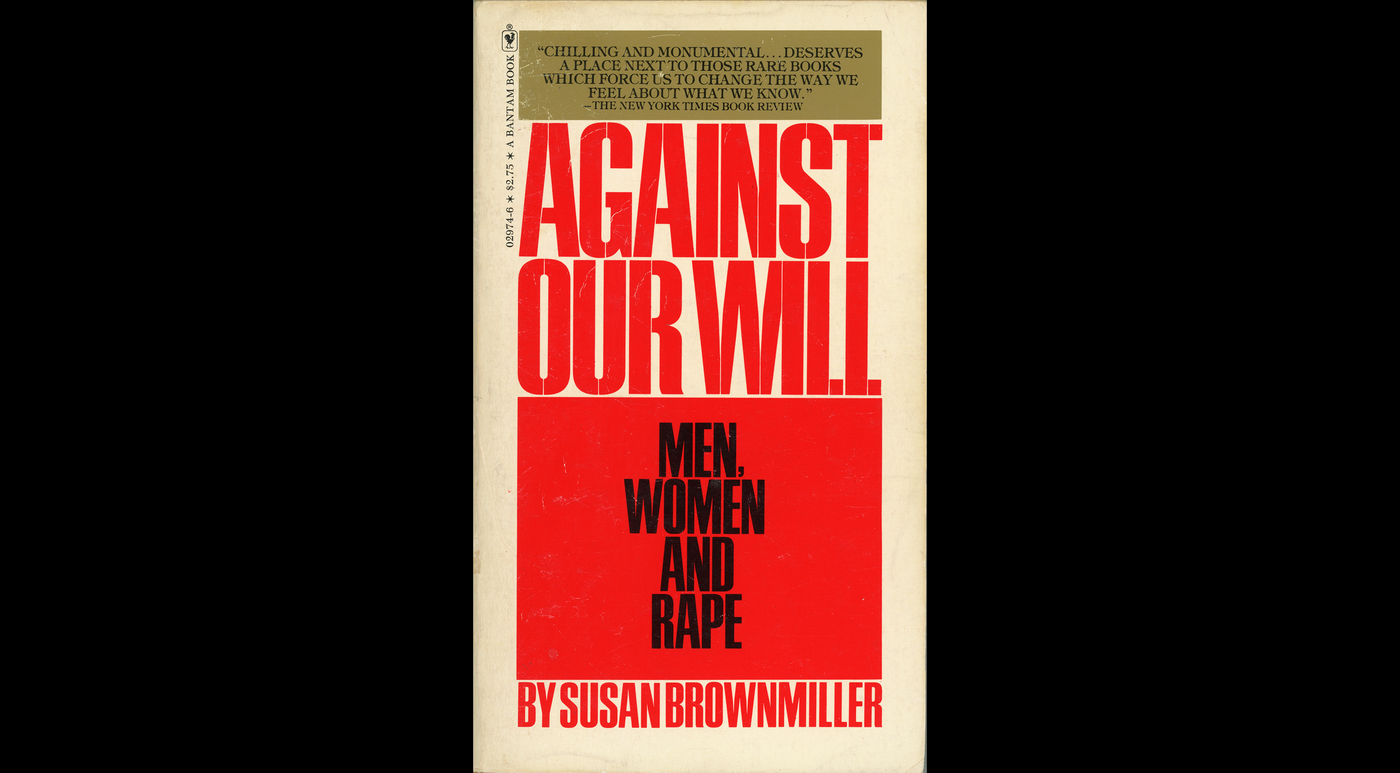

In 1975, Brownmiller took advantage of a rising wave of interest in radical feminism to publish Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (Simon & Schuster). It became a surprise best-seller, and the legal, social, and political conversations about rape that it produced helped to raise public awareness not just about the crime but also its larger political meaning. The book played a significant role in sparking the legal and social reforms that eventually made it possible for people of all genders to challenge sexual violence.

Against Our Will was a triumph, but not universally praised, and its reception illuminates early tensions within feminism. Some arose in Brownmiller’s immediate circle of white women, where she was accused of using ideas “that belonged to everybody” to promote herself. The book also angered leading Black feminists. Angela Davis famously broadcast a multipart series on San Francisco’s KPFA, detailing for listeners why Against Our Will was, in her view, a racist book that recirculated sexual myths about Black men.

Perhaps because Brownmiller invested her political and media skills in political groups that sought to hide and diminish their members’ most significant cultural achievements, and because she became a symbol for feminism’s broader racial problems, her contributions to the movement have been undervalued by historians as well. An influential postwar feminist intellectual, she has been partly relegated to the chorus line of writers, theorists, and activists outshone by Gloria Steinem, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Catharine MacKinnon, Betty Friedan, Shirley Chisholm, Andrea Dworkin, and Ellen Willis.

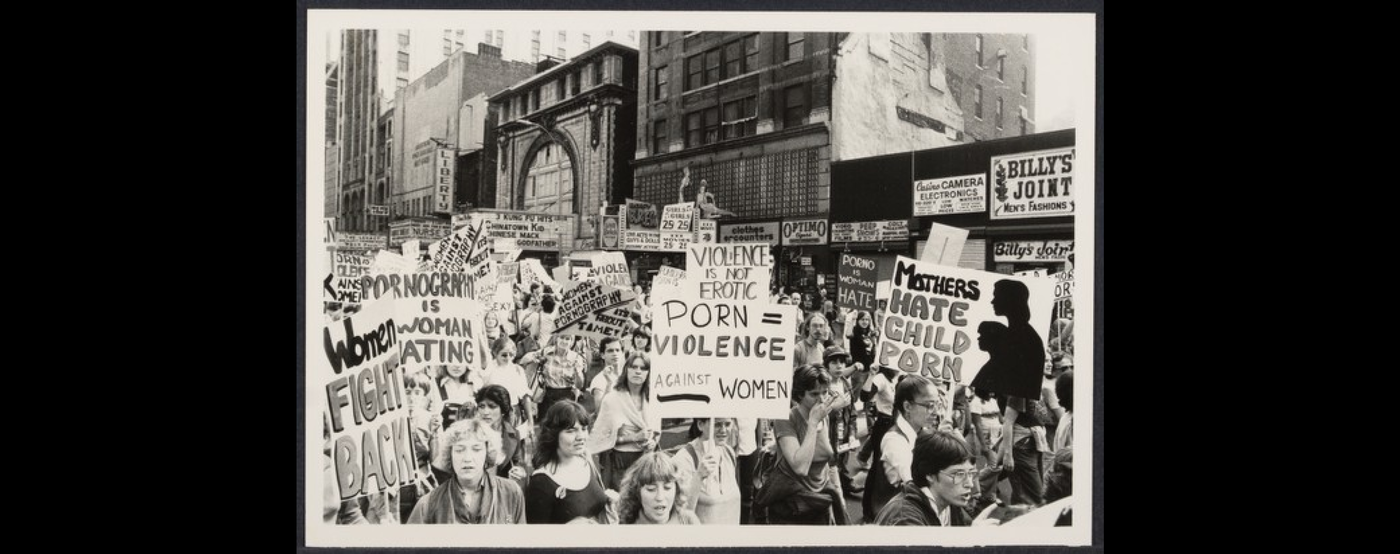

Yet Brownmiller changed history. And she did so again in 1978, when she decided to invest her time, and significant royalties from Against Our Will, in Women Against Pornography (WAP), a New York grassroots antipornography movement headquartered in New York City’s Times Square.

Without her organizing, the so-called “sex wars” of the 1980s—including attempts to make harm from pornography a civil crime—might never have had the impact they did, on feminism or on United States politics. In subsequent years, Brownmiller continued to explore the often-deadly ramifications of sexism for women in essays, books, and personal appearances. By the 1990s, when feminism’s momentum had shifted to a new generation, Brownmiller worked to keep its original ideas before the public in a memoir, In Our Time (1999), and by participating in documentaries and interviews that archived radical feminism’s achievements.

Susan Brownmiller’s life offers a deep dive into how one woman came to feminism and used the movement to realize long-cherished radical ideals. It reveals that, after 1969, politics and journalism were transformed by a woman whose entire life had schooled her to expect that radical equality in the United States was possible. Most importantly, Brownmiller’s story establishes that, although it stalled, restarted, and made mistakes, radical feminism persisted to inflect new movements that elevate people of all genders and races with its vision for social transformation.

Claire Bond Potter is professor of historical studies at the New School for Social Research, and the author of Political Junkies: From Talk Radio to Twitter, How Alternative Media Hooked Us on Politics and Broke Our Democracy (Basic Books, 2020). She is currently writing a biography of Susan Brownmiller.