I’m no family historian. But an unexpected confluence of events turned me into one.

Like a lot of endeavors that seem easy at first, my search for my paternal great-grandmother, Ruth Standish Baldwin, started small but kept growing, never quite reaching closure.

Faded photos and files came out of hiding, email flowed in, and my relationship with Google changed from casual acquaintance to close colleague. One link led to another—and another. The online archive newspapers.com offered vivid, if often distorted, snapshots of daily life a century ago.

In 1921 Ruth was a 56-year-old widow, living in midtown Manhattan with her husband’s cousin Emma Louisa Baldwin—Cousin Lou. Two years earlier, Ruth had sold their house in Washington, Connecticut; later they would move to New Canaan, Connecticut, my hometown, to be closer to Ruth’s son, William. Ruth’s daughter, also named Ruth, lived in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Between them there were five grandchildren.

One was my father, who knew Ruth not as a kindly, indulgent grandmother but as a formidable presence. As my research continued, I began to slowly piece together images of Ruth, including one in the household where my dad grew up.

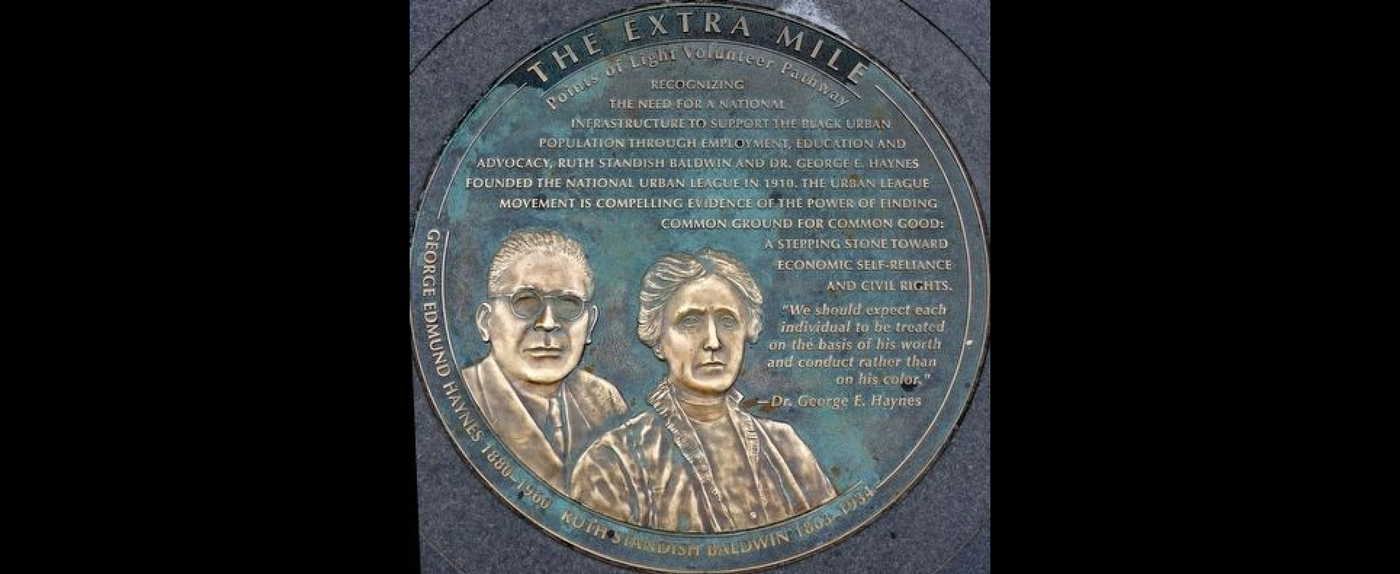

I never met her—she died 15 years before I was born—but I would hear about her. It was often in terms of the men in her life, sometimes in terms of her own achievements: great-grandmother Ruth graduated from Smith College. She was a founder of the National Urban League. She championed Tuskegee Institute and was a friend of its founder, Booker T. Washington.

But there was more, as I learned only after weeks at my computer turned into months and my running notes grew to 10,000 words.

All this digging was made possible by the curse of the pandemic and its gift of time. New School Professor Gina Luria Walker had tracked me down in early September 2020, explaining that she was director of the Women’s Legacy Project, launched during the school’s centennial in 2019 to document the importance of its 10 “founding mothers”—Ruth, to my surprise, among them. I was no longer working 9 to 5, but also no longer free to travel, socialize, or even visit the gym. Would I be able to work on a profile of Ruth? Sure, I said.

I wasn’t expecting to find much, figuring I could see what was out there and report back in a few weeks. Seven months later, I was still making my way in a land of Googleable Ph.D. dissertations, book excerpts, archived letters and news stories, and email from relatives and other sources. A three-ring binder full of memorabilia, compiled and handed down by my parents, proved helpful in tracing Ruth’s genealogy and even provided a bit of information about Cousin Lou. She was, my dad’s notes warmly recalled, famous for her pies.

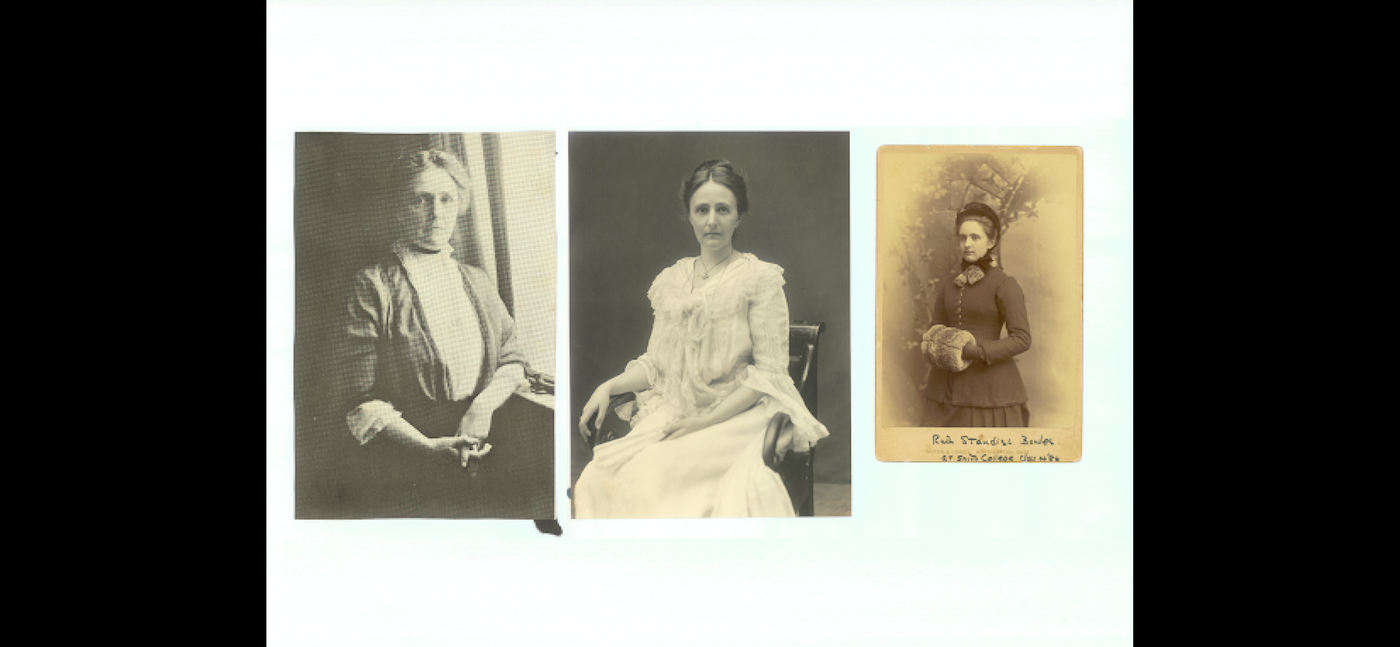

A worn manila envelope had surfaced when my siblings and I emptied our parents’ house, and when I finally opened it I found pictures of Ruth at different times in her life, in one case as a stiff-backed matron, in another as a young girl, her demeanor seeming sweet and thoughtful.

In keeping with the male-centric way we have all learned history, I easily gravitated to stories about the men in Ruth’s life: her father, Samuel Bowles, a leading journalist and abolitionist, and a close friend of Emily Dickinson’s…her husband, William H. Baldwin, a railroad baron and social-reform-minded Unitarian. Eager to create a narrative, I borrowed from an 1874 news article to set the scene one day when William’s father—another Unitarian activist-philanthropist—boarded a train in Boston with a group of like-minded men and headed off to Concord, Massachusetts, where, to my fascination, they paid calls on Ralph Waldo Emerson and Amos Bronson Alcott. Alcott’s daughter Louisa May met them at the door and asked them to sing for her invalid mother.

The narrative soon spun out, spanning nearly a century. But learning about the women in Ruth’s life was a challenge, not simply because newspapers covered men differently from women. (Men traveled. Women received them.) It also had to do with the way we are trained to think about the past. I was able to glean biographical information about Ruth’s mother, Mary Sanford Dwight Schermerhorn Bowles, but not the things I wanted to know. I found descriptions of the household Mary ran, in Springfield, Massachusetts, and the fact that she claimed Miles Standish—another historic male figure—as an ancestor. But with six other children to raise, was it Mary’s idea to send Ruth off to a progressive girls’ high school in New York City? Was it Mary who encouraged her to forge on to then new Smith College?

I never learned how Ruth met her husband, William, Jr., but there was no shortage of information about him, thanks to his gender and high profile in business and civic circles. Energetic, demanding, judgmental, William’s passions included “cleaning up” New York City and promoting Tuskegee Institute. He played a major role in channeling Northern money into Southern Black education, which he and Ruth viewed as essential in freeing the descendants of slaves from entrenched poverty. It was a cause Ruth ran with after his death at the age of 42, working with other social reformers, including outspoken women like Mary White Ovington, a founder of the NAACP, in expanding William’s quest to work more broadly for equal opportunity. Within five years Ruth had attained visibility as a cofounder of the National Urban League.

She identified herself as a Progressive, a pacifist, and a socialist. Late in life, she was a founder of the Highlander Folk School, a social justice center that trains community and labor organizers.

One of my cousins took an interest in the Ruth project and passed along intriguing histories of the Urban League and of the Black scholar W.E.B. DuBois, who split away from Ruth and William to champion a more potent racial justice movement. Soon I was off on a tangent involving the emergence of the NAACP—not quite on topic but, with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, suddenly, eerily, relevant. In the isolation of my home office, feeling the push and pull of historical and contemporary drives for justice alike, the past and present merged.

The more I read and thought about my immediate family, the closer its past felt, too. Now a grandmother myself, I saw Ruth more vividly than I thought possible, as if time had collapsed and she were in the next room, scolding her grandchildren to behave like little Edwardians, stiff and brave and true. I could almost see her at age 15, listening to her father sermonize about emancipation, and to her teachers explaining why women’s education matters. I could feel my own father squirm under his Grandmother Ruth’s steady gaze, the impact of her emotional distance and regard for discipline channeled through generations all the way to my own.

Did I ever gain a full picture of Ruth? Hardly. Most of her letters were lost in a flood. I found no diary, no recollections of her childhood or her years at Smith, no love letters, no record of how she felt about marriage or motherhood or even her philanthropic work, nothing about her relationships with other women, not even her companion of 34 years, Cousin Lou.

All or some of this may surface another day, to the surprise and satisfaction of other researchers. For now, the outline of a narrative is in place, one woman’s life just coalescing behind the retrieved facts.

Deborah Baldwin is a New York writer and editor—and a great-granddaughter of Ruth’s. She graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and has an M.A. in journalism from the University of Oregon. Deborah has worked for The New York Times, This Old House magazine, Common Cause magazine, and Real Simple, and has written for numerous publications, including The Times and The Washington Post. She is currently a part-time editor with PassBlue, a news site that covers the United Nations with a special focus on women.