The history of royal women has long fascinated both scholars and the general public, leading to the rise of queenship and royal studies as thriving academic disciplines. While it is the very visible women, like Cleopatra, Elizabeth I, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and Catherine de Medici, who have attracted many readers and drawn both students and academics into the field (myself included), there are so many other royal women whose lives have been omitted or ignored in narratives of national histories, curricula, and even in queenship studies itself. Increasingly, my own work on royal women has been about drawing out the figures that Theresa Earenfight noted were “highly visible, often obscured” as well as those who were often obscured and have remained largely invisible.

I have tried to bring this idea of rediscovering or recovering those royal women who have been pushed out of the spotlight from my own research and publications into both my teaching and the wider public sphere—in public talks and engaging with other educators.

My own research on queenship began in medieval Europe and involved an obsession with the ways in which women could inherit land and, more significantly, the throne. A long-standing interest in Eleanor of Aquitaine had drawn me to the 12th century, but I became far more interested in a knot of five reigning queens in the Crusader States whose significance as female rulers had been largely hidden in wider male-centred histories of the Crusades. I continued my work on female succession and regnant queenship for my doctoral studies—again finding another sizable knot of ruling women, the queens of Navarre, who had received very little attention outside of scholars who specialised in the history of the region. This work on Navarrese history led me on to my current research on Joan of Navarre, who became first duchess of Brittany and then, in her second marriage to Henry IV, queen of England. While her long life was incredibly eventful and interesting, including the dubious distinction of being accused of witchcraft and detained for several years, she remains one of England’s least well-known consorts. Indeed, Jane Austen noted in her own potted history of England that “It is to be supposed that Henry [IV] was married, since he had certainly four sons, but it is not in my power to inform the Reader who was his Wife.”

The other spur of my research has been to extend the focus in queenship and royal studies from the European to the global. While there are still many obscured European royal women, like Joan of Navarre, the situation is even more acute in a global context, where countless women’s lives are in need of feminist historical recovery to restore their presence in the fabric of the events and movements of both past and present. It has been supposed that different religious, cultural, and monarchical frameworks have restricted or eliminated female agency, but the lives of royal women around the world and new research on their lives demonstrate that this is categorically not the case.

This desire to highlight the royal women who have been missing in the historical narrative, in Europe but particularly in a global context, has been reflected in my own teaching and disseminating of my work to the wider public. My undergraduate and graduate classes encourage students to learn about the lives of royal women, and indeed women, with whom they are unfamiliar from premodern Europe to Africa, Asia, the Americas, Australasia, and Polynesia. This in turn has led my current and former graduate students to create Team Queens, a blog with very active social media networks that work to highlight the lives of royal women across the globe and the centuries with their #QOTD (Queen of the Day) posts, which feature a biographical summary and links to further reading. Speaking about my research to the wider public via talks and podcasts brought me into contact with many educators who are keen to expand the curriculum, as women’s lives are rarely the focus of the narrative or are inserted via a few select case studies like Florence Nightingale or Elizabeth I. I was inspired by their requests for help and have been giving talks to their secondary (middle/high) school students, sending materials for lesson plans for primary and secondary teachers and developing annotated biographies to help more teachers integrate materials on premodern royal women in various periods and regions for ACLS. I also spoke at a lecture series on “Hidden and Marginalised Histories” for both current teachers and those in training on the lives of obscured royal women in European and global history.

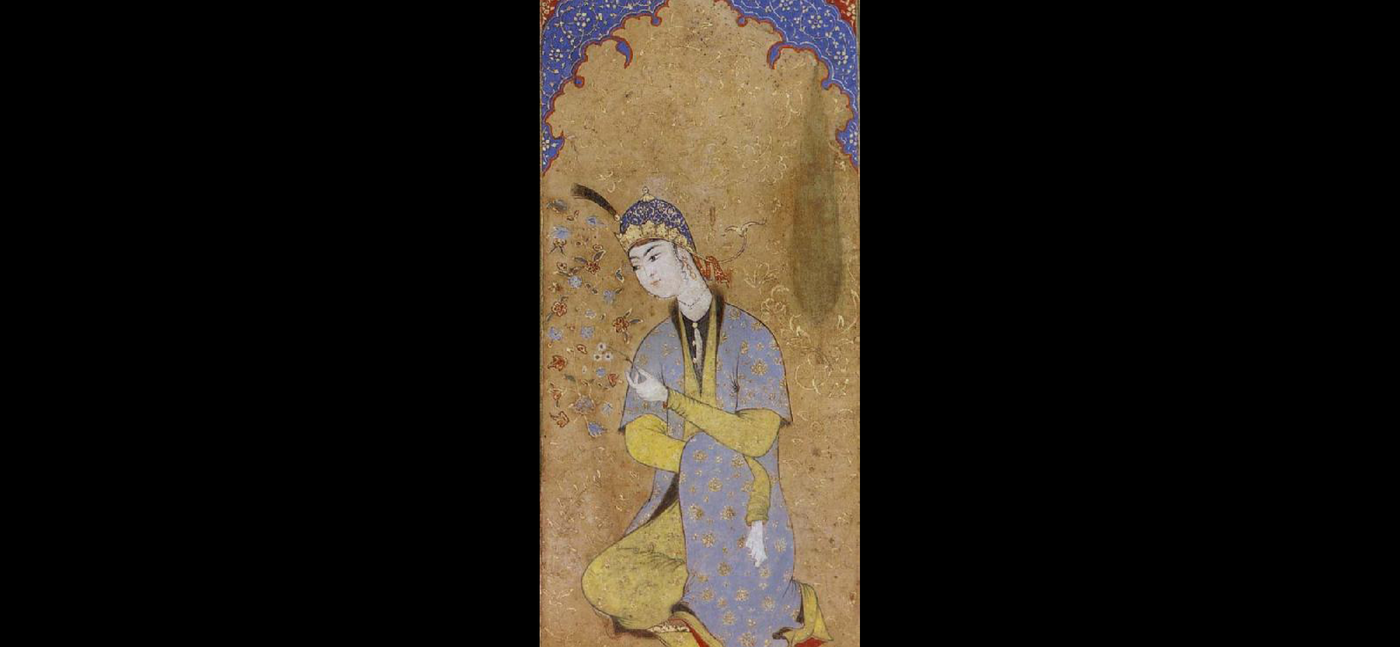

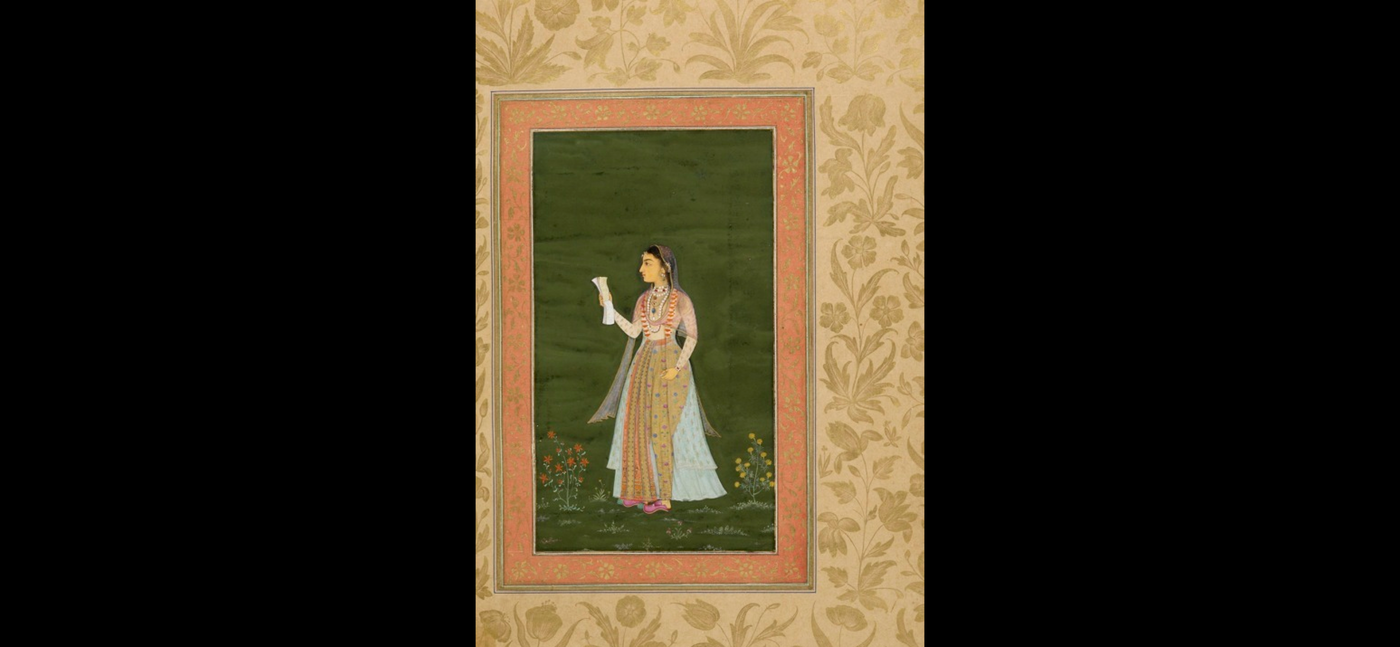

I believe that this three-pronged approach to increase research on the lives of women whose stories have been omitted or obscured, and applying that research via teaching and dissemination, is our best way to drive historical recovery. It is in moving the focus from the ivory towers of academia to the halls of primary and secondary schools that we can really affect change by inspiring young people with the lives of women in the historical past, demonstrating that women played a pivotal rather than supporting role in our histories. We need to change the narrative, and indeed change the curriculum where we are able, so that future generations are as familiar with Arwa of Yemen, Jahanara Begum, Aliquippa of the Iroquois, Chengtian of the Khitan Liao, Eleni of Ethiopia, Pari Khan Khanum, Pomare IV of Tahiti, and indeed Joan of Navarre as they are with Elizabeth I, Cleopatra, and Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Dr. Elena (Ellie) Woodacre is a Reader in Renaissance History at the University of Winchester. She is a specialist in queenship and royal studies and has published extensively in this area, including her most recent monograph, Queens and Queenship (ARC Humanities Press). Elena is the organizer of the Kings & Queens conference series, founder of the Royal Studies Network, editor-in-chief of the Royal Studies Journal, and the editor of two book series with Routledge and ARC Humanities Press.