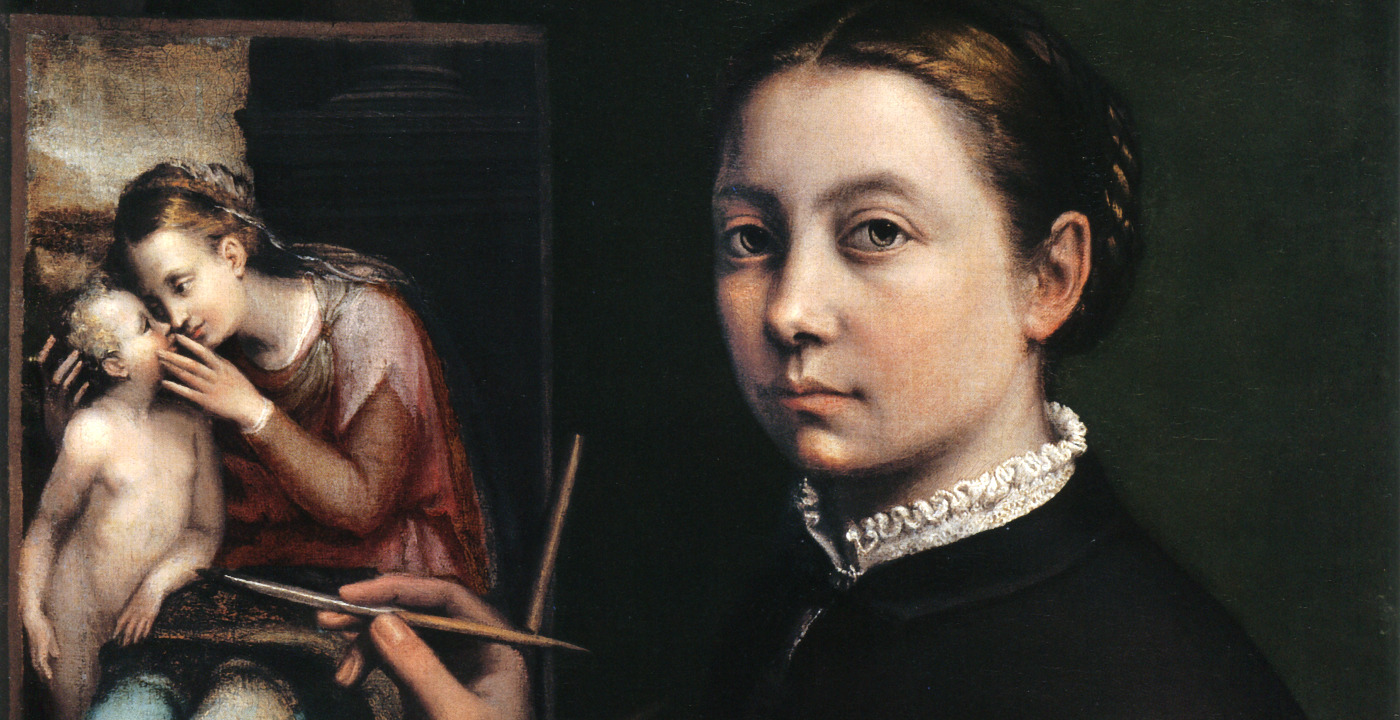

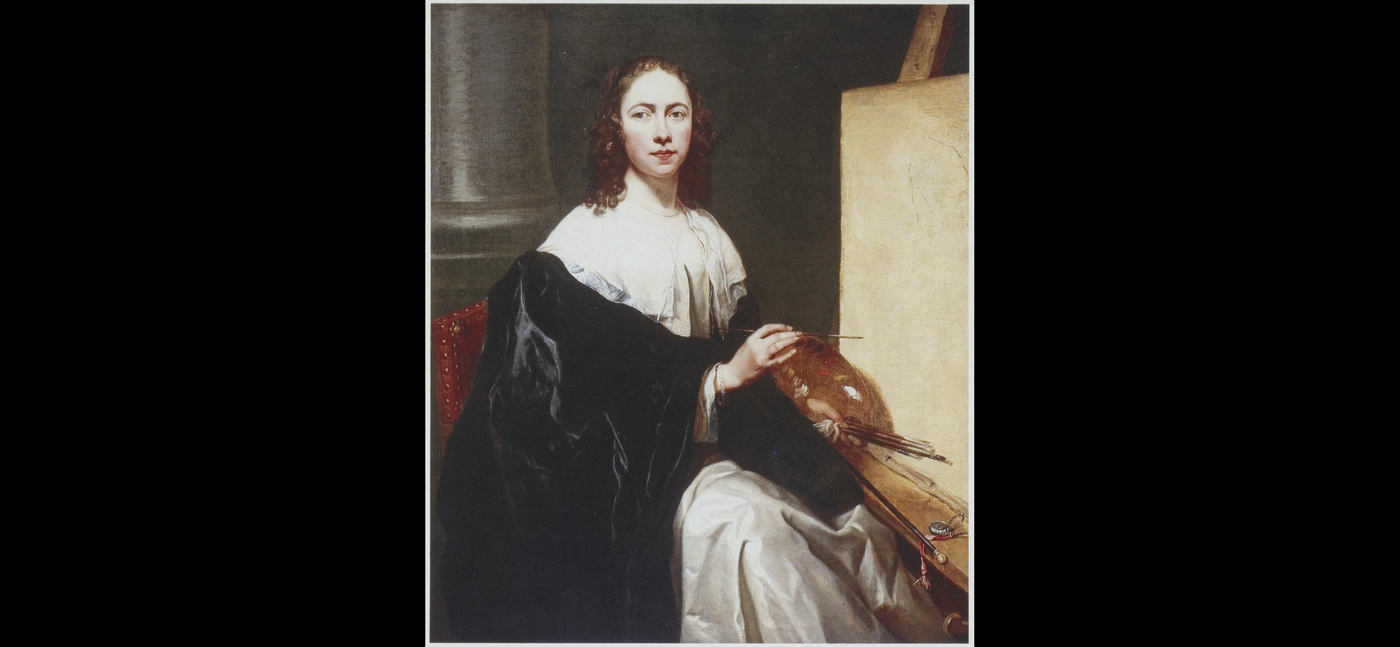

As an acquisitions editor in academic publishing, I have long worked with scholars across the humanities who research the lives of women of past centuries. Today, the world of the arts is abuzz with exciting discoveries about female Old Masters. Art historians, museum curators, art dealers, biographers, dramatists, and authors of historical fiction are among those whose work focuses on history’s women artists. But apart from a rare few such as Artemisia Gentileschi, the names of the once-famous female artists whom scholars are rediscovering are still not familiar to most members of the museum-going public. For many of these historical figures, the interested reader will find few, if any, books published about them—and certainly not authoritative nonfiction that is written for the nonspecialist.

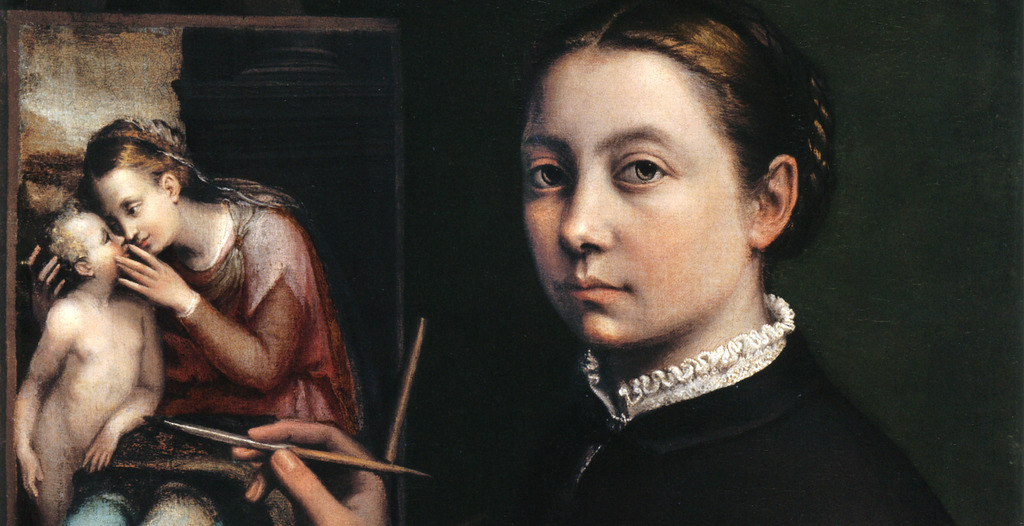

My work with Art Herstory was born of a desire to share information and new discoveries about female Old Masters, in particular, with an audience beyond scholars: art lovers, feminists, students, and other nonspecialists. I have always had a weakness for fine stationery—especially fine art stationery. But I was baffled by my inability to find, in any museum shop, fine art note cards featuring works by women artists from a period prior to Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, or, at the earliest, Mary Cassatt. So, with more enthusiasm than understanding of retail culture, I decided to make women artist note cards that could be sold to, and through, museum shops, as well as directly to mail-order customers.

Three years from the time the first batch of Art Herstory cards were printed, only a small number of book and museum shops carry this new stationery line. But as the number of books and exhibitions to do with women artists grows, the number of Art Herstory retail customers is slowly increasing. And it is a great joy to receive emails, even phone calls, from individual customers, expressing how much it means to them to learn about—to discover that there even existed—famous and successful women artists in the past, at least as far back as the Renaissance.

On the strength of that reception, Art Herstory has added two platforms for shining a spotlight on history’s women artists: a presence (with a growing audience) on social media; and the Art Herstory blog, which publishes richly illustrated guest posts by art historians, curators, authors, and others whose goal is to recognize and celebrate women artists of all historic periods.

So, the mission of Art Herstory is the mission of The New Historia in microcosm. The two projects overlap and intersect to a great degree. Both participate in today’s movement to bring to light the achievements of women in all spheres of accomplishment—including, but not limited to, the visual arts—going back centuries; in the case of The New Historia, perhaps millennia.

And both projects grapple with this central question:

If women of past centuries were so talented—if their contributions to human history were so profound—why do they need to be rediscovered now? Why haven’t their names been included in the historical record from their own day until the present? Were they left out by accident, or on purpose? Just how exactly did this state of affairs come about?

Presently, I don’t have a clearcut response to propose; but the issue is integral to the intense, ongoing work of both Art Herstory and The New Historia. It is essential to explore the question in order to come to grips with the past, and to ensure a fuller, more inclusive, and more accurate historical record as we go forward. In the inaugural Art Herstory guest blog post, historian Merry Wiesner-Hanks writes that “…a failure to take female Old Masters into account leaves us with a short view, which impoverishes the question and limits our understanding.” To extend this sagacious observation to embrace all women throughout history, who contributed to every field of human endeavor, is to make the case for the significance of The New Historia.

Erika Gaffney has worked for more than two decades as an acquisitions editor in scholarly publishing, with an emphasis on early modern studies and/or art history. Currently she acquires books for Amsterdam University Press and Lund Humphries; until 2015, she was a publisher with Ashgate. In 2019, she launched the Art Herstory project, which supports the cultural movement to recover the stories and works of female artists of past centuries. Erika lives in northern Vermont.