When children are taught in school about the founding of America, white male figures fill the cast of characters. Looming large like gods, men such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, Nathan Hale, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton show up on tests and become embedded in the minds of youth as the heroes of the story. These men are the "Founding Fathers," the men whose stories are integral to understanding the history of the United States of America.

What if we stopped saying "Founding Fathers" and started saying "Founding Figures" or, perhaps, even "Founding Mothers"?

Which women, hidden and erased from history, would emerge from the shadows of our past? Would the story of an enslaved Black woman from New York become as integral to our history as Goerge Washington’s? Could she be a Founding Figure, even if she did not invent anything, was not wealthy, and had no political power?

The woman I am referring to is called Liss, known to some as Elizabeth, and her achievement is different from that of the ‘Founding Fathers.’ She has a story that sheds light on the circumstances and conditions of the twenty percent of the population who were Black and enslaved in New York when America became a free country and whose stories continue to go untold. In this way, she is a Founding Figure, a woman whose fight for freedom is pivotal to understanding the development of a free America.

Liss was born on Long Island, New York, around 1763, and she was enslaved by two wealthy brothers named Samuel and James Townsend, who each owned fifty percent of Liss—but they were only among the first of many to enslave her. She would be bought and sold five more times before she turned twenty-five. Understanding her struggle for freedom is enough to make her life worth learning. What I discovered over the course of my research was that her story crossed paths with all of the well-known historical figures listed above. Through her tale, I encountered the Sons of Liberty, the Boston Massacre, the first published Black author in America (Jupiter Hammon), the first known slave freed on Long Island (Tom Gall), the Battle of Brooklyn, the Great Chain, the Benedict Arnold treason plot, and the lead spy in New York City during the Revolutionary War, the son of her first enslaver Samuel Townsend, Robert Townsend, aka “Culper, Jr.” of the Culper Spy Ring. These connections to well-known figures and points in history anchor her narrative in people’s minds, enabling Liss to provide a truly inclusive story of America’s birth.

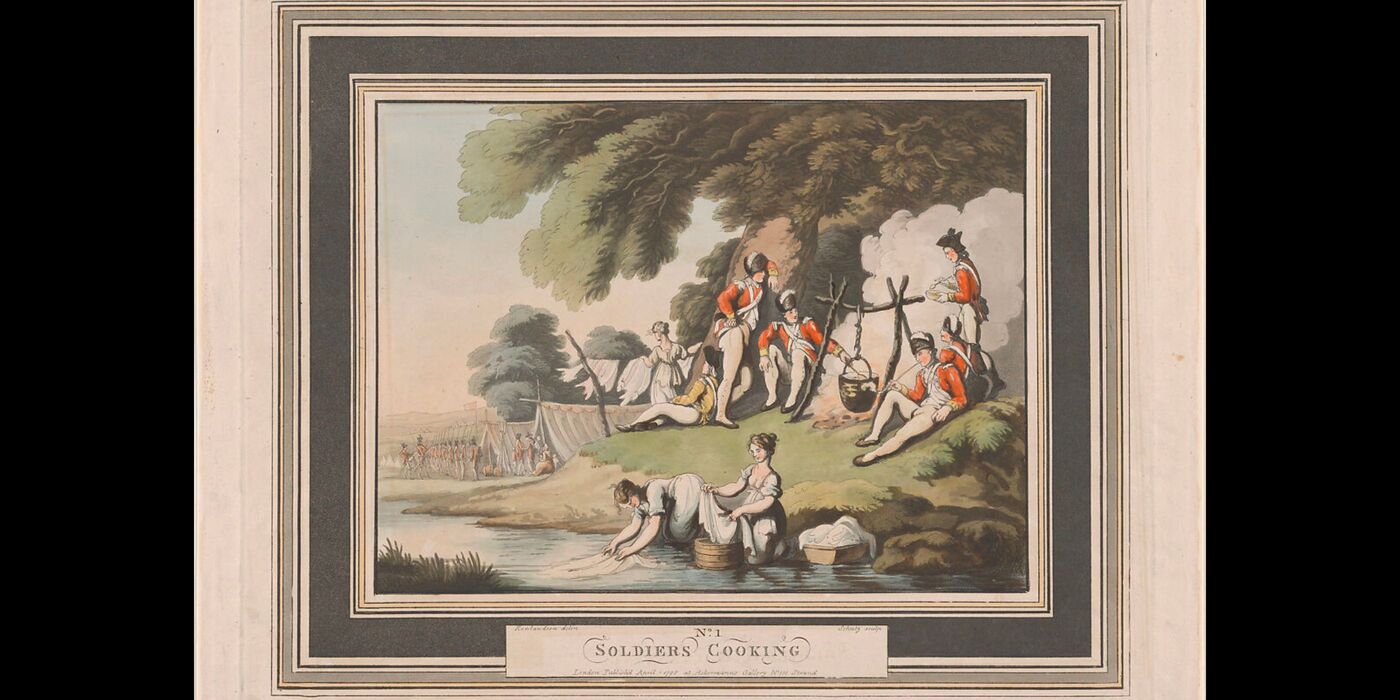

Like all true stories, hers is a complicated one, and it takes many unexpected turns, especially after the onset of the Revolutionary War. The brothers, Samuel and James Townsend, who had inherited Liss were members of the New York Provincial Congress in 1775 and 1776, a Patriot governing body organizing local resistance efforts against the impending attack on New York by the British. When Long Island and New York City were captured by the British in the autumn of 1776, Samuel Townsend and his family were forced to billet British officers in their home, including many commanding officers of encamped regiments. For Liss and over a dozen other Black people enslaved on the property, this added a significant burden to their daily labors.

In 1778, a British commander and early abolitionist named Col. John Graves Simcoe stayed in the house for the entire winter. Liss was seventeen years old at the time and was described by Robert as being “too fond of the British officers.” Chances are Simcoe spoke to Liss with a level of personhood almost unknown to her. Around this time, the British were preparing to announce a proclamation that promised freedom to enslaved people after the war if they escaped and joined the British effort. Simcoe, who later became the Governor of Upper Canada, and ended legal slavery there, knew about the proclamation.

With incredible agency and bravery, Liss escaped with Simcoe and his regiment as they left Oyster Bay on May 18, 1779.

Evidence of Simcoe purchasing a set of large hinges and nails suggests he may have concealed Liss. Eight days after her escape, Robert Townsend wrote to his father revealing the location of Simcoe’s regiment. Since the officer's movements were secret, Robert’s knowledge suggests he was following them, perhaps as part of his intelligence gathering. In the letter, Robert offers to inquire with members of the Queen’s Rangers about her escape, writing, “when I see any of the officers will make inquiry for Liss,” but then Robert changes gears and tells his father that Liss will probably never be recovered, and that Samuel should simply forget about her and deduct her value from his accounts as a “dead loss.” It is possible that Robert knew of Liss’s plans to escape and may have hoped to embed her with the enemy to provide information. While these theories are difficult to substantiate, the Townsends did not place the typical “runaway slave” notice in the newspapers. Liss was soon re-enslaved by another British officer in Manhattan, just as Robert became the lead spy for George Washington. Two entries in Robert’s ledger books show he had contact with Liss in New York City during the years when he was a spy.

When Liss’s British enslaver was about to evacuate in 1782, Liss–who was three months pregnant–appealed to Robert to help her stay in New York City by “re-purchasing” her. Robert agreed. He hired a white maid to do the housekeeping, which may indicate Liss was not required to work. Robert, unlike others in his family, came to believe that slavery was morally wrong, perhaps because of his interactions with Liss. Her son, Harry, was born in February of 1783, and would be later be described by Robert as "mixed-race."

Despite his beliefs, when Harry was six months old, Robert sold both Liss and the baby to a widowed woman named Ann Sharwin, who promised Robert she would not sell Liss and Harry or take them out of Manhattan. Perhaps, Robert did not want to own a slave, or maybe Liss felt the Sharwin household would be a good fit for her and her baby. It is also possible that Robert and Liss had a disagreement that led to her leaving his household, but it remains unclear as to why Robert sold her. Liss knew Ann, and seems to have been agreeable to this new arrangement. However, a year later, Ann married a wealthy merchant named Alexander Robertson—but the marriage was tumultuous. The new couple fought, and the union was dissolved within a month.

Out of spite, greed, or both, and unbeknownst to Robert, Alexander Robertson sold Liss south to Charleston, South Carolina, and kept her two-year-old son Harry in New York City.

In Charleston, Liss was enslaved by a violent man named Richard Palmes who had been the instigator of the Boston Massacre of 1770. Palmes is featured in famous paintings of the event, such as “Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770” by William L. Champney. In the painting, Palmes has a large club raised in the air, and it was he who struck a British captain, causing the officer’s gun to accidentally discharge, ultimately triggering the massacre that killed five civilians, including Crispus Attucks, a Black stevedore who is considered the first person to die in the American struggle for freedom. Palmes’s violent behavior continued well after the revolution, defining his time with Liss.

After two years, Robert, who had since joined the Manumission Society, a New York based anti-slavery group, discovered what had happened to Liss. He confronted Robertson, took four-year-old Harry from the household, and brought him to Oyster Bay. Robert then began a months-long effort to locate Liss and bring her back to New York. Unfortunately, the Manumission Society had succeeded in passing a law prohibiting slaves from entering New York, so it appears Liss was smuggled back to Oyster Bay, perhaps aboard Robert’s ship, the Betsy. In 1789, according to records from the Baptist Church of Oyster Bay, Liss is listed under the name “Elizabeth,” and in 1790, “Free Elizabeth” is listed as a paid servant in the first Federal Census working at an estate called Fort Neck House in present-day Massapequa.

After the death of the two Townsend brothers in 1790, it would take another thirteen years for Liss to attain her legal freedom, which came about on September 3, 1803, when Liss was approximately forty years old. An 1806 record lists her as a congregant in the Baptist Church, with an additional notation suggesting she remained a congregant in Oyster Bay for the rest of her life, where Robert and her son Harry also lived.

Liss’s remarkable story stands as a reminder that brave and resourceful Women of Color have been part of America from the very beginning. What is more, it raises the question of what one must do to be elevated to Founding Figure status, and whether the pantheon might still have room to include a Black woman’s journey towards freedom during the time when America fought for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Claire Bellerjeau is the co-author, alongside Tiffany Yecke Brooks, of “Espionage and Enslavement in the Revolution: The True Story of Robert Townsend and Elizabeth”, published in May 2021. In 2022, she co-founded a 501(c)3 non-profit organization called Remember Liss, with the mission to educate the community about Liss’s extraordinary life and times. Through the non-profit, she co-authored and published a student version of Liss’s story titled Remember Liss in March 2023, with links to over 100 primary documents through the New York Archives’ teaching platform, “Consider the Source.” Bellerjeau formerly served as Historian and Director of Education at Raynham Hall Museum in Oyster Bay, New York, where Liss was once enslaved. She has been researching the Townsend family and those they enslaved for over seventeen years, including curating a yearlong exhibit on the Townsend “Slave Bible” in 2005. In 2015, during a research visit to the New York Historical Society, she discovered what may be one of the earliest poems ever written by Jupiter Hammon, America’s first published African American writer. She has developed educational programs on the subjects of slavery in New York and the American Revolution on Long Island and works with teachers to develop curriculum to share Liss’s story using primary documents from her research.