Queen Tamar, the Monarch of integrated Georgia, was named “The King of Kings and the Queen of Queens of Abkhaz, Georgians, Rans, Kakhs and Armenians, Shirvans and Shakansh and Lord of the entire East and West, greatness of the universe and faith, messenger of Messiah.” Her reign left an indelible mark on the history of Georgia.

Tamar’s father, King George III was afraid of being ousted in favor of his nephew Demna. To secure his grip on power, he issued two explicit demands: Demna's castration and blinding and that his daughter become his co-ruler when she reached the age of 12. In a society unaccustomed to female rulers, everyone expected her to be relegated to a subordinate role, first subordinate to her father and then to an appropriate husband. However, Tamar defied these expectations.

For the initial six years of her reign, Tamar ruled alongside her father without any major disruptions, which brought relief to the nobility. But upon King George's death in 1184, she shattered the conventional image of what was expected from someone of the so-called "weaker sex."

Tamar forged alliances with senior members of the royal family and with the leader of the Georgian Church, Michael IV Mirianisdze, reinforcing her rightful claim to the throne. Though initially coerced into a marriage with the Rus Prince Yuri, Tamar later publicly accused him of misconduct, sodomy, and drinking, leading the nobles to approve her divorce. Yes, Tamar divorced him in the 12th century, in a Christian nation, where the church expressly forbade it. This went beyond a simple separation. Tamar persuaded the bishops to formally dissolve their matrimonial ties, granting her the freedom to enter into a new marriage, and exiled Yuri to Constantinople. Despite his two attempts to return, Tamar found a new suitor in the form of the Alan Prince David Soslan, whom she married out of genuine affection and love. Together, they successfully fended off Yuri's challenges, solidifying Tamar's position as a remarkable and unconventional ruler (Metreveli 1991).

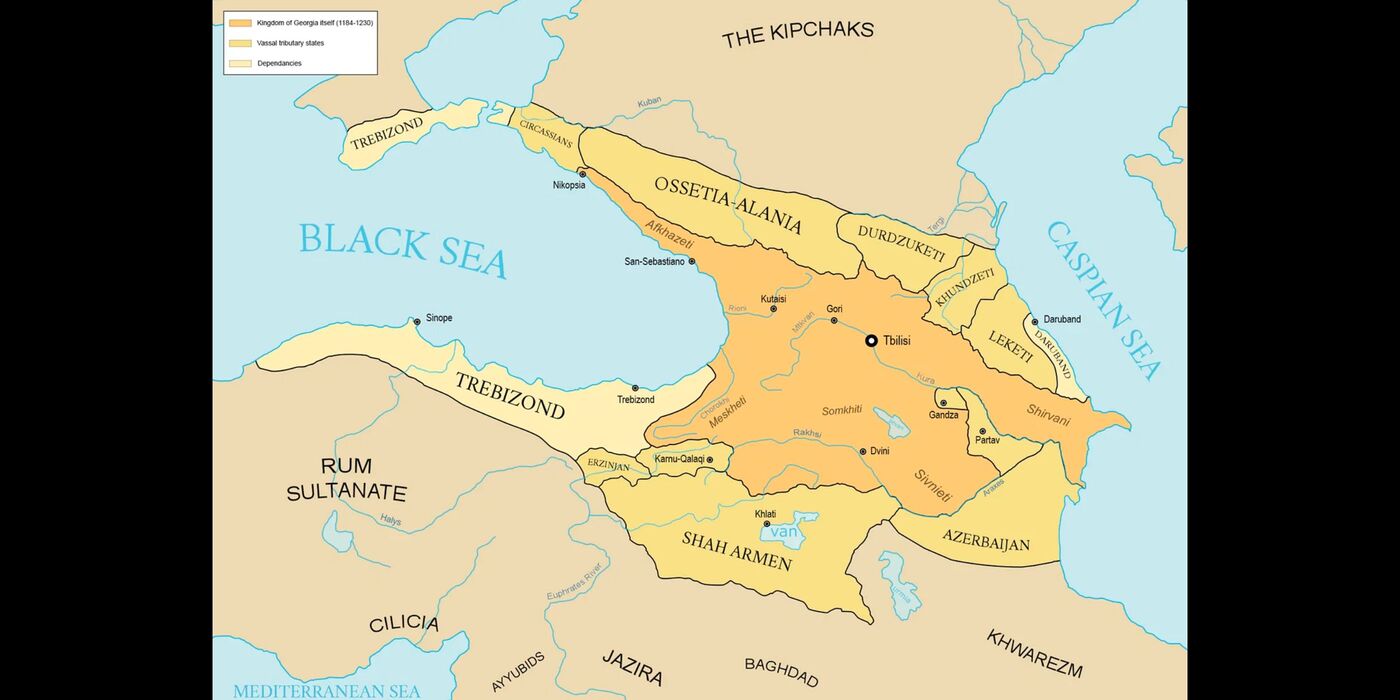

Georgia was in the midst of a global religious conflict, and Tamar spent much of her life in warfare, following her armies across the Caucasus. Officially, Tamar didn't lead the armies; she accompanied them, delivered inspiring speeches, and retreated to the nearest monastery to pray for victory while her husband took charge. However, some theories suggest she might have had more influence in military matters than official accounts suggest. Tamar achieved significant victories, overcoming two rebellions led by her ex-husband, facing off against the formidable Rum Sultan, and establishing an empire in Trebizond. Under Tamar's leadership, Georgia reached its greatest size and became the most powerful country in the region.

She governed the most extensive territory Georgia had ever held. Tamar's achievements extended far beyond the battlefield - she was a remarkable reformer who managed to unite numerous kingdoms and principalities within Georgia, ushering in what is widely regarded as the nation's Golden Age. Under her rule, Georgia began to find its own national identity, a unique blend of East and West. Tamar's royal treasury thrived, leading to a flourishing of ecclesiastical art, literature, and splendidly illustrated manuscripts. Under her patronage, new cathedrals were constructed, and iconography was adapted to emphasize her unparalleled beauty and wisdom (Janashvili, 1917).

It was a period characterized by compassion. Tamar abolished her father's severe criminal penalties, banned torture, and the death penalty, and chose not to employ punishments like whipping, blinding, and castration. Tamar also endorsed remarriages and upheld Georgia's longstanding tradition of religious tolerance. This period elevated Queen Tamar to a position unparalleled in her country's pantheon of heroes, surpassing even her male medieval counterparts like Vakhtang Gorgasali and David IV Agmashenebeli.

When Tamar became queen, she faced a rebellion from the nobility who didn't like her father's policies. They also doubted a woman's ability to rule. Tamar was forced into a marriage to produce an heir, the nobility continuing to believe she needed to be subordinate to someone else because she was a woman. This shows how gender restrictions affected her power. The limitations on Tamar's authority continued. In 1187, her first husband tried to overthrow her, supported by many Georgian aristocrats who wanted a return to traditional male rule. In 1203, the Sultan of Rum gathered armies with a clear message: he believed that women were weak and simple-minded, making them unfit to rule a country. Consequently, he presented Tamar with two options: surrender and convert to Islam to become his wife, or surrender, maintain her Christian faith, and become his concubine.

Tamar defeated him.

In 1205, a ruler from Seljuk, Rukn ad Din invaded Georgia, citing Tamar's gender as the reason. It seems that during this time, societies in Anatolia and the Caucasus saw women rulers as a hindrance to the kingdom's authority and military strength. But after the initial rebellion, Tamar's gender became less of an issue. Gaiane Alibegashvili, who has authored two separate books on the known contemporary portraits of Tamar, notably does not emphasize gender as a defining factor in the portrayal of the queen, except when considering her physical attributes and beauty (Alibegašvili, 1944). Tamar's rule is celebrated due to her perceived asexuality and in my point of view, her success can be attributed to her resilience and ability to defy traditional expectations of women in power.

Gender held greater prominence in Western literature concerning Queen Tamar, with Antonia Fraser's "Boadicea's Chariot: The Warrior Queens" being a notable example:

“Queen Tamar succeeded lawfully to her father to the acclaim of her people. she added to both the prestige and the dominions of her country and died leaving a legally begotten male heir to succeed peacefully in his turn. in actual fact, her gender, so far from detracting from all this glory, seems to have added to it” (Shanks, 2004).

W.E.D. Allen endeavored to convey a comparable sentiment through words in his 1932 historical account, but his attempt proved equally enigmatic: "The peculiarly maternal sway that a benevolent female ruler wields over the hearts and minds of men was prevalent throughout her rule." Gender is perceived as a prominent, yet paradoxical element in the achievement of Tamar's reign. In fact, these writers pinpoint gender as the very factor that distinguishes Tamar's Golden Age as an exceptional occurrence (Allen, 1932).

Throughout her life, Tamar was a woman deeply devoted to her faith, maintaining strong connections with the Georgian Orthodox Church for strategic, personal, and spiritual reasons. Following her demise, the church took an extraordinary step by canonizing her as Saint King Tamar. This was significant for two reasons. Firstly, prior to Tamar, there were very few female saints in the Georgian canon, with notable exceptions being Saint Nino and Saint Queen Nana of Iberia, who had lived nearly 900 years before Tamar. Secondly, akin to her secular subjects, the Patriarch and other prominent church figures continued to refer to Tamar as "King."

Georgia was governed by several queens, but only Tamar was given the title of “mepe” or “king.” Tamar was hailed as the "Master of the Lands," "King of Kings," and “Queen of Kings.” It is said that at that time, there wasn’t much of a linguistic distinction in the words that Georgians used; there was not a word in the language for a woman monarch because there had never been such a thing. Or maybe she herself wanted there to be absolutely no confusion about her intention – which was to rule exactly like a king – and started calling herself a “King of the Kings”. This might be accurate, but in my view, it goes back to the fact that a woman was in a position that was unusual for her, a position that was meant to be created for males. Whether one viewpoint is correct or another, it is still evident–women did not have their space, neither in the dictionary nor in the public sphere.

Tamar likely passed away around 1213, in the vicinity of Tbilisi. Her passing was met with widespread grief among her subjects. The profound influence she had on her nation was eloquently encapsulated by the author of "The Life of Tamar, King of Kings," a prominent chronicle within the compendium known as Kartlis Cxovreba (literally translates as The Life of Kartli):

During those days, the name of Tamar was the foremost topic of conversation. Acrostics, paying homage to the queen, adorned the walls of houses, while rings, knives, and pilgrims' staves were inscribed with her praises. Everyone sought to articulate words befitting of Tamar's name; even ploughmen composed verses in her honor as they cultivated the land. Musicians arriving in Iraq commemorated her with their melodies, and both Franks and Greeks extolled her virtues while sailing the tranquil seas. Her praise resounded throughout the entire world, spoken in various languages wherever her name was recognized (Javakhishvili, 1944).

Her remains were initially brought to the Mtskheta Cathedral and later interred in the royal necropolis at the Gelati Monastery. However, the trail grows cold thereafter. In a 13th-century letter from the French knight Guillaume de Bois, there is a suggestion that he encountered Tamar's son, King Giorgi-Lasha, in the Holy Land, where he was transporting his mother's remains for burial near Jerusalem. Present-day scholars have, as of yet, been unsuccessful in pinpointing the exact location of her grave.

Renowned poets of the era, such as Shota Rustaveli, drew inspiration from her life and works and wrote in the 12th century in his poem The Knight in the Panther’s Skin: “Lion cubs are equal, be they male or female”. She was immortalized in folk songs, and myths emerged, suggesting that Tamar had conceived her son through a sunbeam passing through a window, portraying her as a goddess of fertility and healing. Similar to the pagan deity Pirimze before her, she was believed to have the power to control the weather. Even during her lifetime, Tamar was venerated in almost divine terms. A Graeco-Georgian colophon and the late 12th-century Vani Gospels, believed to have been composed at the Roman Monastery in Constantinople at Tamar's request, declared her a saint.

These accomplishments carry a poignant significance as Tamar marked the end of the great Bagrationi rulers in Georgia. Within two decades of her passing, the Mongol invasions laid waste to the administrative and military systems that had facilitated such expansion. While subsequent periods witnessed national revivals, such as the reign of Giorgi the Brilliant, ultimately halted by Temurlane, none could quite match the remarkable combination of achievements that defined the era of Queen Tamar.

Tamar ascended to the role of an anointed king due to the circumstances. She shattered every prevailing stereotype associated with her gender and emerged as the most outstanding of Georgian rulers. Her achievements are commemorated by the Georgian Orthodox Church on her saint's day, the 14th of May, yet Tamar and her remarkable feats deserve to be acknowledged and celebrated on a much broader scale.

However, it should be noted, that her father, King George III appoints Tamar as co-ruler not because of her political and diplomatic skills, which she has shown in numerous situations, but for the simple reason – she has no brother. Later on, Tamar just gets “lucky” and has a son, the heir to the throne and a commander of Georgia. If nothing else, from the surviving frescoes, she is always depicted with men–father or son, or both. Her daughter, Rusudan, is nowhere to be seen. This is how Queen Tamar was created in relation to men. She has become men’s possession. Men told stories about her, men wrote dissertations, books, or poems, and men made her a saint. Perhaps this is the reason why Queen Tamar could not become a feminist symbol. But the time has come and whether as a King or Queen, saint or a mortal figure, Tamar can stand as an inspiration for all of us.

***

This is part one in a series of editorials dedicated to celebrating the resilience of Georgian women. The histories of women challenging societal norms and advocating for gender equality have often been obscured by misogynistic veils. This series aims to shed light on the lives of five extraordinary Georgian women spanning the centuries, each contributing uniquely to the ongoing narrative of feminism. From the Middle Ages and the reign of Queen Tamar to the early 20th century, featuring the feminist pioneers Maro Makashvili, Kato Mikeladze, Ekaterine Gabashvili, and Barbare Jorjadze, these women carved unique paths in Georgia, challenging the limitations placed upon them. By weaving together the stories of these remarkable figures, this series seeks to explore the diverse dimensions of Georgian feminism and unveil the collective strength that transcends temporal and societal boundaries.

These women, with their fighting spirit, can become a source of inspiration for many people, if only they are known. Their ideas provide solid ground for the empowerment of women, which is no less important today than it was hundreds of years ago. Everyone should be familiar with the heroes who are lost to the labyrinths of history, who fought against stereotypes and misogyny—stereotypes that, for some reason, are passed down like an incurable disease.

Works cited:

Janashvili, M. Tamar Mepe. Tbilisi: Georgian Women’s Society of Tbilisi, 1917.

Metreveli, Roin. Mepe Tamari. Tbilisi: Ganatleba, 1991.

Fraser, Antonia, and Rosalind Shanks. "Boadicea’s Chariot: The Warrior Queens." London: Royal National Institute for the Blind, 2004

5A history of the Georgian people. by W. E. D. Allen.

Javakhishvili, Ivane. The Life of Tamar, King of Kings. Georgian National Academy of Science, 1944.

Alibegašvili, Gaiane. Četyre Portreta Caricy tamary: K istorii portreta V gruzinskoj Monumentalʹnoj živopisi. Tbilisi, 1957.

Tata Jagiashvili is a graduate student at The New School in New York City, pursuing a master's degree in Media Management. She is a Public Engagement Fellow with The New Historia. Tata holds a bachelor's degree in Social Sciences from the Free University of Tbilisi in Georgia.