Queen Puduḫepa was an influential ruler of the Hittite Empire. She reigned alongside King Ḫattušili III (ruled ca. 1267-1237 BCE) and held notable levels of political, social, and religious power. She began her life as a priestess of a land foreign to the one she eventually ruled over as the Great Queen. Much of what is known of Queen Puduḫepa’s life can be discerned from her recorded words and deeds.

Puduḫepa’s name, originating from the Ḫurrian language, means “the goddess Ḫebat gave birth to her.” She was born to a high priestly family in Kizzuwatna around 1300 BCE and is identified as “the daughter of Kizzuwatna,” which may mean she was a princess in that ancient Anatolian kingdom, but the accuracy of this supposition is unclear.

In 1274, Ḫattušili III–the brother of the Great King of Ḫatti, Muwatalli II–married Puduḫepa while returning from a battle with the Egyptians at Kadesh. Her exact age at this time is unknown. In reference to his marriage, Ḫattušili wrote:

“When, however, I returned from Egypt, I marched to the city of Lawazantiya to bring offerings to the goddess, and worshiped the goddess. [A]t the behest of the goddess I took Puduḫepa, the daughter of Pentipšarri, the priest, for my wife: we joined (in matrimony) [and] the goddess gave [u]s the love of husband (and) w[i]fe. We made ourselves sons (and) daughters…I became King of Ḫapkiš while my wife became [Queen of] Ḫakpiš” (Hallo and Younger, eds. Translated by Theo van den Hout. 1997, 202).

The region of Ḫakpiš, north of Ḫattuša, the traditional capital city, supported Ḫattušili in his efforts to usurp the throne from his nephew, the son of Muwatalli II. The successful coup made Ḫattušili the Great King and Puduḫepa the Great Queen; they reigned from the capital, Ḫattuša.

In his autobiographical text, Ḫattušili credits his personal goddess, IŠTAR-Šauška, as his protector and supporter, attributing the surety of his success to the messages the goddess conveyed to Puduḫepa in her dreams, in which she assured Puduḫepa of Ḫattušili’s accomplishments. According to the written texts of Puduḫepa, IŠTAR-Šauška’s voice was decisive and powerful; Puduḫepa’s dreams signify her domestic and international involvement in political affairs.

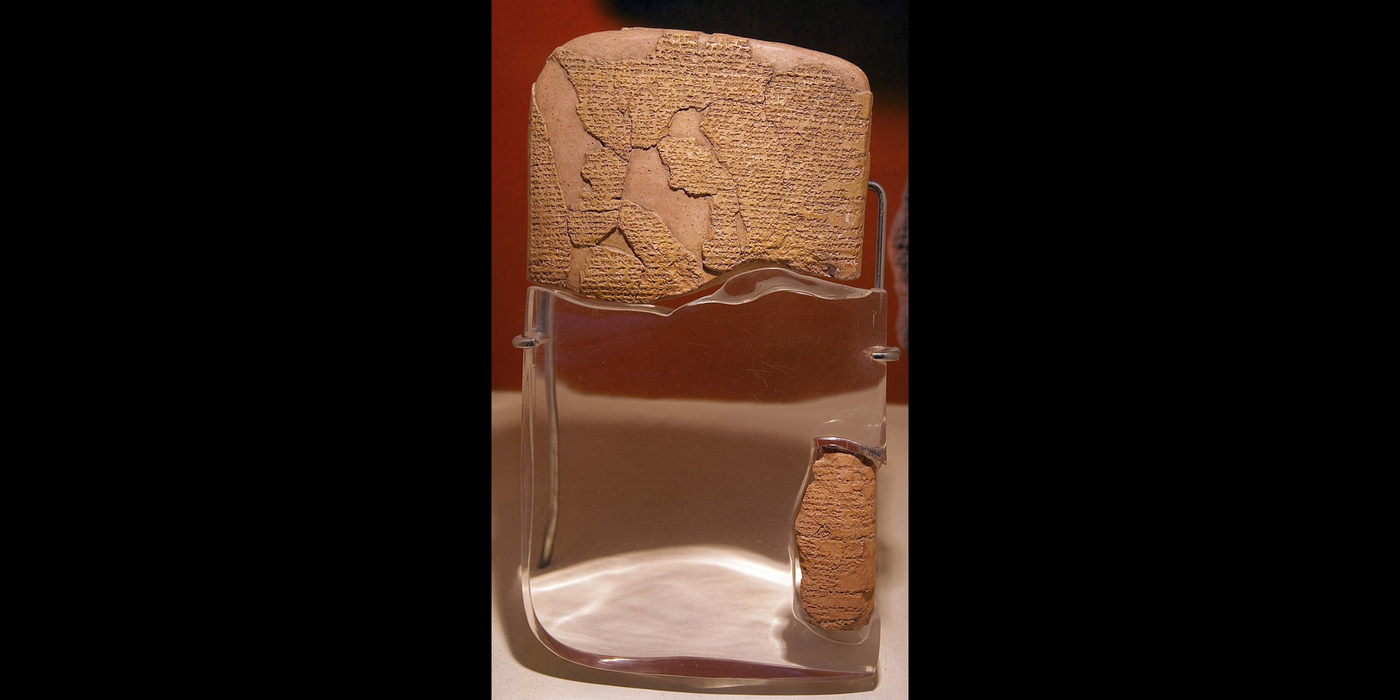

This involvement is also signified by the stamp-seal impressions bearing Puduḫepa’s image that were left behind. These included seals of Puduḫepa alone, seals of her together with Ḫattušili III, and seals of her and her son, future king Tudḫaliya IV. One such stamp-seal was found on a communication of great international importance to the kingdom, a peace treaty with the Pharaoh of Egypt, Ramesses II.

The Pharaoh was impressed by the seal impression of Puduḫepa on the silver tablet treaty he received. He replied:

"What is in the middle of its reverse: an inlaid figure of the Goddess of Hatti embracing a figure of the Great Lady of Hatti, enclosed by the following border-inscription: 'The Seal of the Sun-goddess ("Pre") of the town of Arinna, the lady of the lands; Seal of Puduḫepa, the Great Lady of the Hatti-land, the daughter of the land of Kizzuwatna, the [priestess? of the town of A]rinna, the Mistress of the land, the servant of the Goddess.' What is inside the surround of the outline-figure: 'The Seal of the Sun-god (sic) of Arinna, the Lord (sic) of every land;' (it should be ‘Sun-goddess, Lady’)" (Kitchen and Lawrence, 2012, 593).

Stamp-seal impressions of the queen were found in Ḫattuša and outside it. Puduḫepa was not the only Hittite queen who owned seals nor the only queen involved in royal administration and international relations, but a larger bulk of her seals and other materials remain today compared to other queens; among these are drafts of letters to the Pharaoh Ramesses II and his wife, Queen Nefertari. In one letter, she thanks the Pharaoh for his gifts, indicating she sent gifts of her own. She then assures him she will give him her daughter in marriage, binding the two kingdoms; however, she will send her daughter without the customary gifts because of the war in which her kingdom is engaged.

Referring to Pharaoh Ramesses II as “brother,” as was the custom between rulers to indicate equality, Puduḫepa then continues,

“Does my brother have nothing at all? Only if the Son of the Sun-God, the Son of the Storm-God, and the Sea have nothing, do you have nothing! Yet my brother you want to enrich yourself at my expense! It (i.e., such behavior) is unworthy of name and lordly status” (Hoffner, 2009, 287).

In the same letter, she brags about marrying her daughters to other great kings, including the king of Babylon:

“If you should say: ‘The King of Babylonia is not a Great King,’ then my brother does not know the rank of Babylonia” (Hoffner, 2009, 283).

And to indicate her power, she describes how she become the mother of many in her royal house:

“Furthermore, when I entered the royal household, the princesses I found in the household also gave birth under my care. I raised them (i.e., their children), and I also raised those whom I found already born. I made them military officers…” (Hoffner, 2009, 287).

Beyond Puduḫepa’s involvement in foreign affairs, she held the prestigious office of the Tawananna, the head priestess of the kingdom. Despite being a powerful commander, warrior, and state leader, her husband Ḫattušili was often ill, and Queen Puduḫepa would pray to the gods to extend well-being on his behalf, perhaps also taking a heavier hand in ruling during his absences. In one prayer, she begs:

"To the Sun-goddess of Arinna, my lady, lady of the Ḫatti lands, queen of heaven and earth: I, Puduḫepa, am your long-time servant, I am a calf of your stable, a stone of your foundation. You, my lady, elevated me and to Ḫattušili, your servant, you attached me, and he too was assigned (lit. by lot) to the Storm-God of Nerik, your beloved son. […] [For] the land of Nerik and for the land of [Ḫakpiš (?)] he placed [his] body and his [life] at risk as long as he held the campaign against [the Kaška enemy(?)]. […] This matter I, Puduḫepa, your maid, made into a case-prayer to the Sun-goddess of Arinna, my lady, lady of the Ḫatti lands, queen of heaven and earth. Yield to me, O Sun-goddess of Arinna, my lady, and hear me! Among humans one often speaks the following saying: “The deity yields to the woman of the birthstool.” [Since] I, Puduḫepa, am a woman of the birthstool (i.e., midwife), and I have devoted myself to your son, yield to me, O Sun-goddess of Arinna, my lady, and grant me what [I ask of you]! Give life to [Ḫattušili], your servant!" (CTH 384.1: Following the text and translations of Hethitologie Portal Mainz (HPM): Translation by Itamar Singer, Hittite Prayers. SBL Press, 2002: p. 101–104.)

The office of the Tawananna was for life. She retained the responsibility, even after Ḫattušili’s death, continuing as head priestess through her son Tudḫaliya IV’s rule. Through this, she held power over the cult that went beyond prayer, controlling the budget allocated for the cult, which granted her significant influence over the economy. Texts left behind by Puduḫepa reveal some of her actions in regards to cultic activity, such as the collecting of rituals from the land of Kizzuwatna for a celebration in Ḫattuša, an act that was likely political, as well as religious.

Evidence of Queen Puduḫepa’s life has survived for nearly 3,000 years. The data suggest that she was an ambitious, influential, and respected woman who used her position to shape her kingdom and the Hittite legacy. Her ascension from priestess in Kizzuwatna to the Great Queen of Ḫattuša allows us to imagine, with the help of documentation uncovered by archeologists, the full story of her life and contributions.

Dr. Ada Taggar Cohen is a professor of Bible and Ancient Near Eastern studies, and the Founder of the Program of Jewish Studies, at the Faculty of Theology of Doshisha University, Kyoto, Japan. Her research focuses on Hittite priesthood and comparative studies of issues related to Hittite and ancient Israelite cultures. Her book Hittite Priesthood (Heidelberg: Universität Verlag Winter, 2006) is a comprehensive work on this topic. For her publications see here.

Works Cited:

CTH 384.1: Following the text and translations of Hethitologie Portal Mainz (HPM): Translation by Itamar Singer, Hittite Prayers. SBL Press, 2002: p. 101–104.

Hallo, William W., and K. Lawson Younger, eds. The Context of Scripture. Translated by Theo van den Hout. Brill, 1997. 199-p. 204.

Hoffner, Harry A. Letters from the Hittite Kingdom. Society of Biblical Literature, 2009. Text 98. p. 281-290..

Kitchen, K. A., and Paul Lawrence. Treaty, Law and Covenant in the Ancient near East. the Texts. Harrassowitz, 2012. p. 593.