Catoctin Cemetery

Shhh!

Quiet yourself.

No talkin up here.

whatever you doin

you got to quit it now.

This here be our lan.

bought wit our life.

They weren’t shamed to do it,

an we ain’t shamed to tell it.

Ever since we could stan

till we couldn’t stan no more.

We worked it

from sunup to sundown

seven days

rain or shine

mosquitoes and snakes

hot or cold

down in the bones.

It’s our lan.

Never did get no

forty acres an no mule.

We done migrated

gainst our will

come over in ships

shackled, chained, starved, beaten.

Some made it.

Soldanbought. Boughtansold

ended up here.

This where we lay.

We was

worked like mules

owned like dogs

fed like hogs

hunted like deer

skinned like buffalo

hung like bats

shot like wolves.

You got to walk careful

You got to walk quiet.

This where we be.

Shhhh!

(Elayne Bond Hyman, 2019)

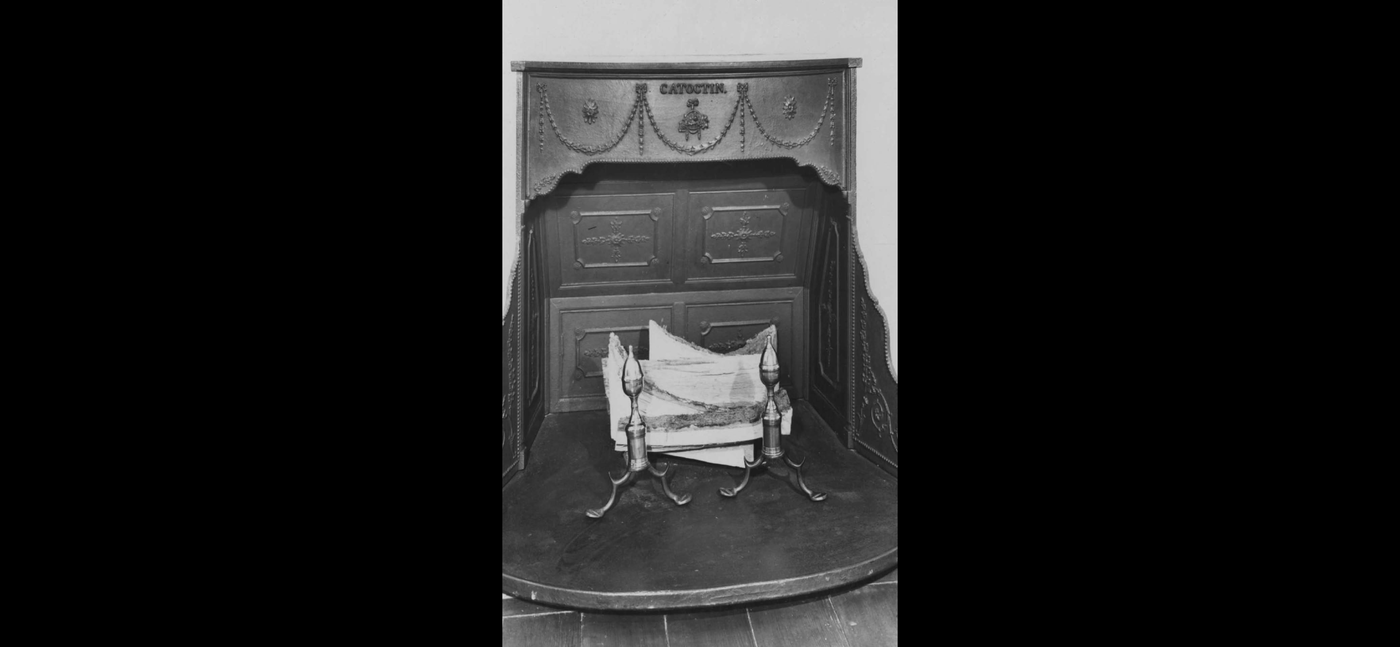

Today, Catoctin Furnace is a quiet, peaceful village nestled at the base of the Catoctin Mountains in northern Frederick County, Maryland. But from 1776 until 1903, the site was a thriving iron-making community, a microcosm of American industrial growth. Workers for iron companies mined the rich ore banks near Catoctin Mountain, smelted it in furnaces, and cast both raw pig iron and iron implements of every description.

Just eleven days after the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, Catoctin Furnace received an order for munitions. One large order in 1780 for 958 ten-inch shells can be linked to the siege of Yorktown.

The furnace site grew into a village complex with a concentration of specialized workers. A charcoal house, casting house, foundry, forge, stables, wagon sheds, sawmill, store, and church were all necessary to the iron operation, not to mention housing for miners, colliers, furnace fillers, founders, forge men, teamsters, blacksmiths, and other skilled workers.

Enslaved Africans provided a large part of the labor force at Catoctin Furnace in the early days. Highly skilled and experienced, these crafts people worked as blacksmiths, colliers, founders, forgemen, and finishers.

While many furnace jobs were undertaken by men, women and children often worked as finishers and cleaners, removing sand for the castings and filing off rough edges. This important final step in the ironmaking process ensured that castings were ready to ship to customers. In addition to making iron, members of the enslaved community toiled in the vineyard and at other agrarian tasks on large farms surrounding the furnace. They also worked as domestic servants for the ironmasters and their families: cooking, cleaning, washing, and tending children. By the middle of the 19th century, the number of enslaved workers at Catoctin declined sharply as large numbers of European immigrant workers moved into the area. Hiring European immigrant labor was cheaper than keeping a large enslaved population.

The Catoctin Cemetery, an African-American burial ground at Catoctin Furnace, was excavated in 1979-1980 as part of a planned highway expansion. The section of the cemetery investigated during this time yielded 35 graves and 33 remains. The skeletal remains were immediately identified as having African origin and were taken to the Smithsonian Institution where they are curated today.

In 2015, the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society, Inc. began a reanalysis of the remains using new technology. In the past, information about the owners of the complex was abundant, but the stories of the enslaved people and free black labor force at the furnace were absent.

With this work, a more inclusive narrative is now possible, changing the interpretation of Catoctin Furnace.

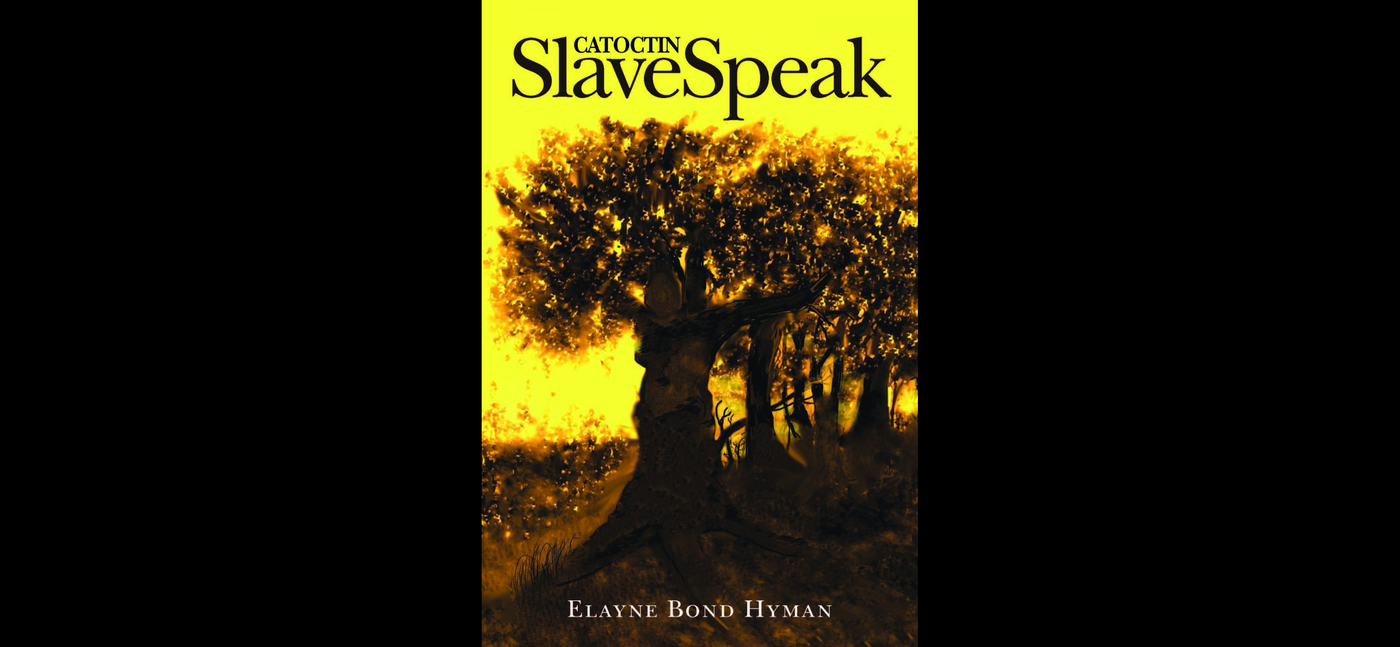

The rediscovery process has been several years in development. A partnership with the Smithsonian Institution and the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School has successfully sequenced the human genome of 29 of the individuals from the Catoctin cemetery. The stated goal of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society in undertaking this research is to identify a descendant community for the Catoctin African-American workers (enslaved and free), to connect the individuals within the cemetery to their ancestral roots in Africa, and to share the discovery process and its results with the public, including information about social status, region of origin, historical ethnicity, familial relationships, working life, dress, health, disease, overwork, diet, birth, and death. It is within this study that Catoctin SlaveSpeak, a collection of narrative poems written by Elayne Bond Hyman, evolved.

The inclusion of poetry in the reinterpretation of the cemetery was not planned or obvious. It began with a visit to the Smithsonian Institution by a group of historical society members, including Ms. Hyman, a retired Presbyterian minister who self-identifies as a mixed-blood woman of Native and African descent from East Coast tidewater and woodland tribes: Chickahominy, Nottaway, and Tuscarora. During the visit, Ms. Hyman said a prayer over the remains and later recounted that the experience included what she interpreted as a request for their story to be told. Her connection continued as she visited the cemetery site and felt compelled to write about specific people described within the archaeological record.

The resulting poems are based on the archaeological and forensic anthropological evidence resulting from the excavations undertaken in the late 1970s and the many hours the author spent walking the earth, visiting the cemetery, studying archaeological and forensic evidence, engaging in quiet listening, and acknowledging intuitive knowing.

These narrative poems, such as “Testimony of the Trees,” represent a new way to bring the past back to life and present information with the emotional resonance it deserves.

“Testimony of the Trees,” among her other poems, is one avenue for rediscovering the lost legacy of African Americans in Catoctin Furnace.

Testimony of the Trees

We’ve stood here for quite a while.

through slavebodies we have grown.

weathering storms of snow and ice

while furnace ash blasted down

our bark grows rough and tough.

Soft slaveskin lines our trunks.

We shelter skeletal remains

work eastfaced is enough.

We felt men bring slavebodies up

tossed them at our roots

Their pinch toe coffins we split wide

their shrouds we have devoured.

Their skin flakes off: dark black, light brown

layering the mud soaked ground

that feeds our brambled grove.

Slavebodies twisted, tangled in

the dirt we hold in place.

The air once fouled with iron ore

a burned up, burning space.

The hills laid bare for charcoal fire

old growth passed out of sight.

We heard their sorrow songs

moaned in the dark of night.

The cry of infants dead,

slavemothers mourned alive.

Lungs struck black with lash and whip.

slavebones crunched with iron chains

slavemarrow feeds us now.

Slavetears pulleyed up our trunks

commingled with the rain

we stand here, live witnesses

sentient to slavepain

while gravestones hide and peek.

When harsh wind blows upon our heads

tearing at our limbs,

Or sun sucks dry small woodland creeks

waste water’s precious drops

We come together branching up

join hands in silent hymns.

We sway toward one another

supported by the songs

slavesvoices whisper from below

and steady us along.

For even in our shadowed grove

slavebodies reach toward life!

(Elayne Bond Hyman, 2019)

Previously, the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society produced most of its research at the formal level, in the form of research papers at professional symposiums and articles published in juried publications. Recently, it has been making efforts to reach a wider and more diverse audience. Poetry, which presents information at the personal level, can evoke an emotional response in a way research cannot, allowing the society to connect in a new way.

The poems within Catoctin SlaveSpeak attest to the power of poetry to express the archaeological process and reach an expanded audience through public art.

The Greatful Dead

By calling out our names at the sound of the chapel bell we are remembered.

By keeping watch over the earth, our sacred place, we are honored.

By studying our bones, dug up and reassembled, we are made human.

By reciting our stories, spoken in the language of poetry, we are resurrected.

Many generations who come upon us will know we are greatful.

(Elayne Bond Hyman, 2019)

Elizabeth Anderson Comer is an archaeologist who serves as the president of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society and president of EAC/Archaeology, Inc. Now completing her Ph.D., Comer has managed the restoration of the log collier’s house, the stone forgeman’s house, the Museum of the Ironworker, the construction of an interpretative trail for the African American cemetery, and bioarchaeological research about the Catoctin Furnace population. She has procured and managed 82 grants totaling $2,802,217.30.