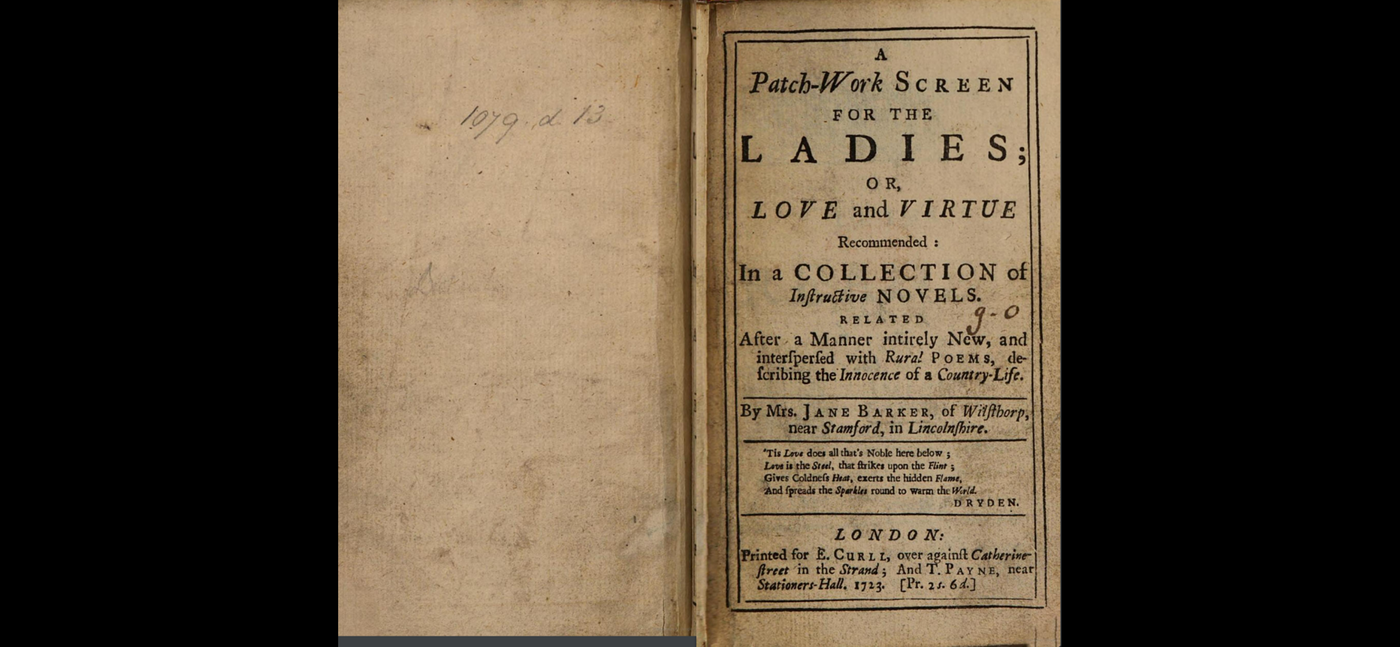

“Why write a history reduced into patches?” wonders Jane Barker (1652-1732) in the preface of her essay-novel, A Patch-Work Screen for The Ladies: a “collection of instructive novels related after a manner entirely new,” published in 1723. Based in London and informally educated in medicine and Latin by her brother Edward, Barker was well-read, a convinced celibate, and a staunch Jacobite who had converted to Catholicism and exiled herself to Saint-Germain-en-Laye when James II fled to England during the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Not exactly the average life of a 17th-century middle-class woman, but in regards to education, political involvement, and awareness of gender inequalities, Barker was not an exception compared to other women from different classes. She also wrote science in her poetry, but her scientific insights were not registered because poetic compositions of this sort are still broadly defined as “poetry.”

Reading Barker’s Patch-Work is an illustrative case of how women’s eclecticism in writing prevented readers and critics from seeing the originality of their content. For instance, Barker explains in her preface to the reader that the story of her protagonist, Galesia, is not a history in the manner of Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders (1722), Robinson Crusoe (1719), and Colonel Jack (1722). Or, she argues, not as the anonymous history of Sally Salisbury, a celebrated prostitute, but rather as a discourse patch-work. She is thus challenging one of the “fathers” of the English novel and the early 18th-century assumption that fiction should render an account of realistic events, usually taking on the form of long and detailed letters exchanged between characters.

In Patch-Work, Barker makes an astute syllogism that she is not a historian although she recalls having read that the biblical patriarch, Joseph, wore a garment of sundry colors. If Joseph did wear a colorful cloak, someone had to produce it—most likely a woman—but there is no written account of who sewed his clothes. Barker restores our awareness that an activity associated with women’s labor is present in recorded sacred history. Barker’s style may be technically weak as a modern work of fiction, as many texts by male writers were also disorganized and patched, but I believe it is a page-turner narrative.

Barker confides to the reader of her romance novel Exilus (1715) that she wrote it while she was in love and hopes this passion is rightly represented. Her circle of acquaintances who read the manuscript before it was published enjoyed the fact that the novel was “free from long speeches, and tedious descriptions of towns, places, sieges, battles, horses and their trappings.” In short, her book has all the trimmings of a historical novel to concentrate on action, characterization, and psychology, which would become a major concern for later novelists. In reference to the philosophers Hester Pulter (1605-1678) and Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673) who wrote about atomism and natural philosophy, Barker threads another caustic punch line on patch-work empiricism: “I have heard some philosophers assert about the clashing of atoms, which at last united to compose this glorious fabric of the universe.” Then, of course, she conventionally apologizes to the reader for “carrying the metaphor too high.” In her “high flight in favour of the ladies,” she has turned into an Icarus of melted wings, now falling head down into reality.

Women writers from the past, such as Barker, do not lack a sense of purpose. In the description of her free-fall, she lands upon a “joyful throng of people of all ages, sexes and conditions,” who rejoice at the “wonderful piece of patch-work they had in hand.” In her fiction, stories told by women are welcomed by everybody and become “a new creation,” almost an instrument of world peace. No less resourceful is Barker’s poem “Anatomy,” a verse description of “nature’s architecture” in which she compares the different parts of the body to housing spaces and elucidates William Harvey’s theory on the circulation of blood. Barker even stitches herself with Ovid, who was known for writing law in verse. Hence, she sets out to do the same with an intriguing foray into medicine. That was indeed—to use a now classical feminist neologism—making “Herstory.”

Despite the growing scholarship on Barker and a 1997 edition by Carol Shiner Wilson, her complete body of works is largely unknown to readers. This is common with most of early modern women’s writing to date, especially with hybrid genre texts such as essay-novels, miscellanies, and religious tracts. Even prolific women authors with a recognizable style of writing are not quite yet reaching bookshops. In fact, we often have more scholarly studies on the life and single works of a particular female author than modern editions of her compositions. With the exception of selected collections edited by academic publishers (Oxford Classics, Iter, Penguin, la Pléiade, or Cátedra), women’s ideas are still widely underrepresented. What is worse, many times they pass unnoticed because the texts are only accessible in their original print, manuscript form, or in facsimile versions. I am reminded of the Neapolitan Laura Terracina whose amorous poetry was published and well-known in many Italian states from the mid 16th-century but cannot be read in any modern edition. Or M. Marsin from 17th-century London, who wrote long essays on “how to put women in the first place.” And the Spaniard Victoria Ossorio, who produced historical poetry in the 17th-century on the Great Siege of Malta against the Ottoman Empire, is gone. How come these writings were lost in the first place?

Contemporary readers may not see the point in delving into the nuances and intricacies of those works, even if they find them page turners of a different sort. The cultural industries may have desisted from bringing those stories to life, but we—readers and scholars—persist.

Persistence comes in a myriad of forms when it relates to recovery efforts. It is born from a realization that the world has been explained from a male’s perspective. Visibility is a fashionable term invoked by many to point at the need of showcasing women creators. But how do we persist in knowing and learning from them? What is invisible?

The recovery efforts undertaken by Project WINK, funded by the European Research Council and led by myself, considers that we may have bibliographies and databases of women’s names, but their input remains largely untouched. The project takes on a trans-genre perspective; one that focuses on women’s works and ideas regardless of the medium or literary genre in which they were produced. Thus, it studies the marginalization of women’s intellectual input in the early modern period (1500-1780) through a process that WINK has critically coined “textual misogyny.”

Ingrained cultural mechanisms of debasing women’s work have led to a non-assimilation of its intellectual value, sustaining an androcentric vision of reality. It contemplates intellectual recovery in the short and long term; a transformative and synergic action across disciplines that takes stock of the brilliant contributions of feminist criticism so far, and leaps forward to another level that is already changing the way we count knowledge-ordering systems and women as equal intellectual partners in a process the project defines as “epistemic equality.”

Another recovery strand is the long-standing effort by The New Historia, a consortium of distinguished scholars spearheaded by Gina Luria Walker. TNH reconstructs the biographies of women and how we tell these life stories and their significance in the historical continuum. In doing so, The New Historia transforms the “missing matter” of women into an active historical force. Both recovery efforts make visible two different but related dimensions of how knowledge is produced and transmitted in history: the lost value of women’s lives and that of their creations.

What does it mean to recover women writers from the past? Are we recovering texts from women differently from how we recover texts from obscure male writers? It is hard to offer a conclusive answer to this, only an awareness of the sizable amount of women’s texts that are materially present but remain intellectually invisible. National libraries and digitizing projects of all kinds are proliferating to make a large corpus of women’s writing available and visually attractive to the public. It is such a massive body of evidence, especially when it speaks several languages, that it’s hard to fathom how so many women’s thoughts have faded. By this, I don’t only mean original thinking generated by women in academic fields such as theology, economy, political or social issues, but also wisdom that has been historically deemed as “feminine concerns,” such as parental care or marriage.

In following the trail of early modern women’s writings, we face the nagging feeling that recovery is far from complete by digitizing, quantifying, visualizing, and making these texts accessible on the Internet. For how long will they remain online once our funding and research projects are gone?

Digital preservation plans and certification of digital repositories, as well as open access, provides availability and awareness of the materiality and readability of these texts. Many of them were already extant in library catalogs. However, a deeper appraisal of their intellectual value may require an effort to de-habituate ourselves, scholars, and readers alike, from the comforts of reading these texts as if they were contemporary novels.

What constitutes valuable thinking and good literature is always tricky, chronically unresolved, and indeed, the wrong question to ask ourselves. Recovering the value of works from the past doesn’t mean that most writing women were intellectuals (as not all writing men were intellectuals, either). Still, their texts may contain original contributions in thought and unconventional ways of storytelling that are worth integrating into the history of ideas.

The growing interest in women's creative output, from the east and west, north and south, across borders and colors, gives us the opportunity to make our research even more meaningful to an attentive readership. A special collective persistence in retrieving, studying, and publishing is required from all corners of the cultural and educational spectrum to cater to readers who are willing to absorb the variety and spirit of early modern women’s writing. “To be transformed,” as Virginia Woolf famously said, “by their moments of being.”

Carme Font Paz is an Associate Professor in English Literature at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain, and Principal Investigator of the Research Project WINK, Women’s Invisible Ink: Trans-genre Writing and the Gendering of Intellectual Value in Early Modernity, funded by the European Research Council.