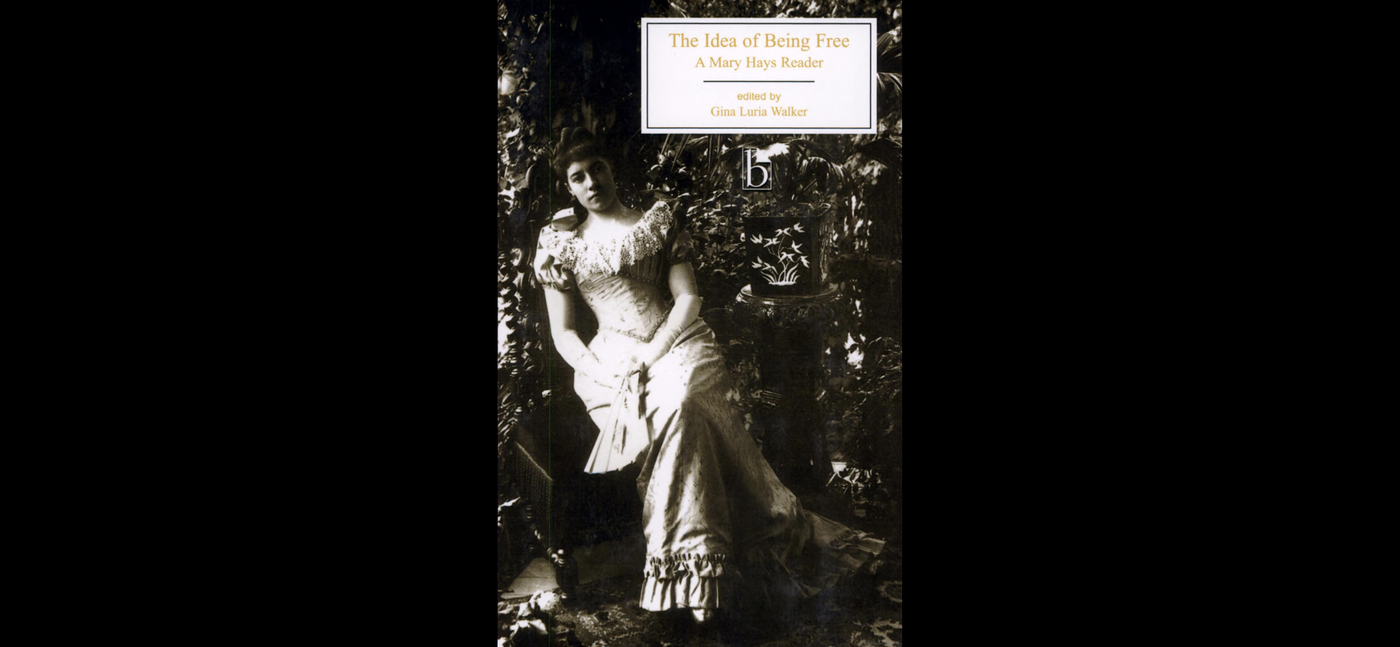

Mary Hays (1759–1843) was a radical writer and feminist who produced an extensive collection of essays, poetry, novels, and writings on significant women. Though her work was critically neglected during her time, her influence was wide-reaching and the quantity of work is comparable to only a few female thinkers of the age, among them Mary Wollstonecraft and Jane Austen.

In A Room of One’s Own (1929), Virginia Woolf lamented her inability to find women writers in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries that she considered “great.” She concluded this was due to women’s lack of financial independence and imaginative autonomy; they did not have the space and solitude necessary to produce significant writings, hence the importance of a ‘room of one’s own.’

For Woolf, Jane Austen was the only great woman writer of her era. Likely, Woolf knew little, if anything, of Hays. But, unlike Austen, Hays had an independent income and solitude when she desired: Woolf’s essentials for the production of original thinking and great literature.

Hays used her financial independence and personal autonomy to achieve her lifelong quest of “the idea of being free.”

To do so, she acquired eighteen “rooms of [her] own” in London and elsewhere. These rooms provided her with the necessary seclusion to fulfill her intellectual aspirations; they were also places of social and familial discourse, where Hays fostered her ideas for moral, political, religious, and educational reform, especially for women.

Before she acquired these rooms, Hays was raised in a strict Calvinistic Baptist family. Dissenting religious sects, such as the Particular Baptists, fostered strong beliefs about the importance of faith and spirituality for each individual, male and female. Mary Hays learned these ideals of individualistic and independent thinking early in her life and never relinquished them. She remained loyal to Dissent and became a devout Unitarian, the most heterodox form of Protestant belief, in the early 1790s and embodied the free thinking ideals of a “household of faith” thereafter.

Her youth was spent in a house on Shad Thames, but in 1776 her widowed mother moved the family into a house on Gainsford Street near a Baptist chapel and next door to her eldest sister, Joanna Hays Dunkin, whose husband, John Dunkin, Jr., would serve as the guardian of the Hays family for the remainder of his life. In this home, Hays conducted an illicit courtship with John Eccles, wrote Cursory Remarks—a critique of a pamphlet by Gilbert Wakefield—and began a turbulent relationship with the Unitarian mathematician William Frend. She also met a variety of friends and colleagues: Mary Wollstonecraft, a Unitarian when they met in the 1790s, William Godwin, a former Dissenting minister, Eliza Fenwick, former Methodist, and Henry Crabb Robinson, a Presbyterian turned Unitarian.

Hays moved across the Thames in 1795 to her new rooms in the household of Ann Cole; this change unleashed her creative and scholarly appetites. From her two residences with Cole between 1795 and 1803, Hays used the libraries of friends such as William Tooke, John Aikin, and Rochemont Barbauld; she used the public reading rooms of London’s premier circulating and subscription libraries and the vast holdings of secondhand bookshops to conduct extensive research in religion, philosophy, history, and women’s lives, particularly their education.

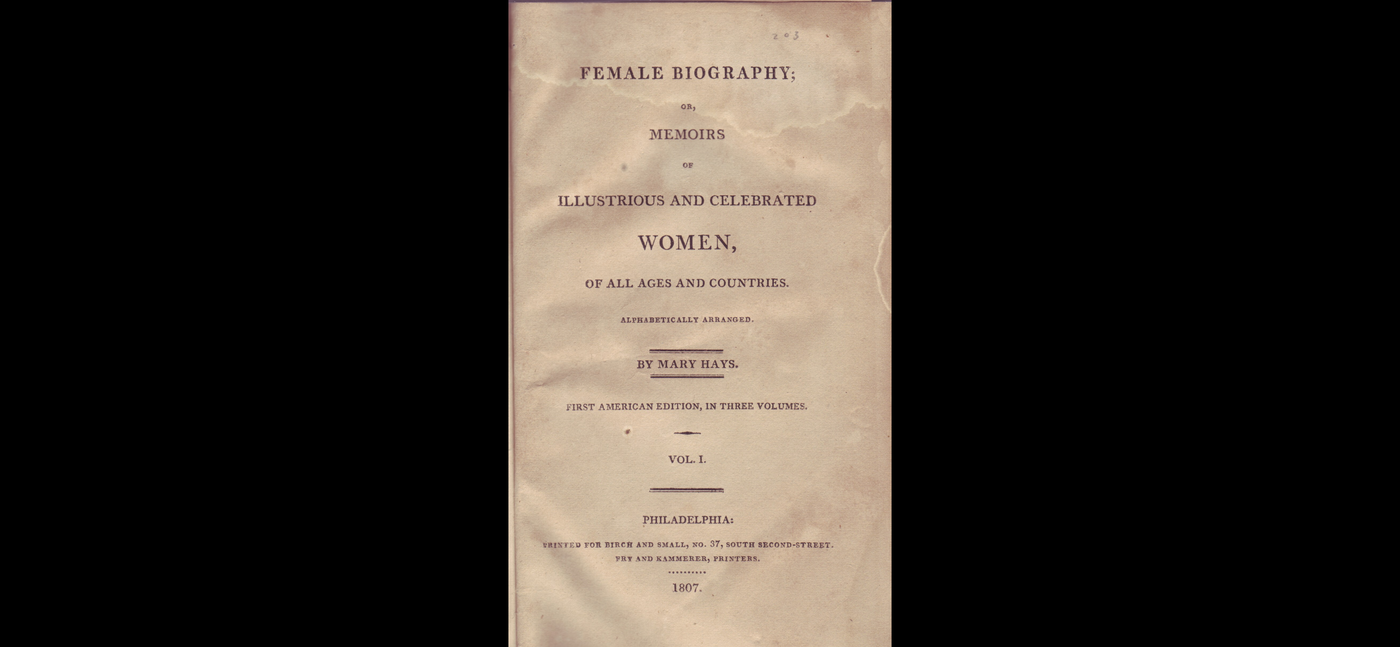

This research led to countless hours in her own rooms composing seventeen periodical essays and reviews for the Monthly Magazine and the Analytical Review; two feminist novels, Memoirs of Emma Courtney and The Victim of Prejudice; a lengthy treatise on women’s rights and education; An Appeal to the Men of Great Britain on behalf of Women; biographies of Wollstonecraft and Charlotte Smith in Richard Phillips’s Annual Necrology; and the first biographical history of women in English by a named woman, Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries (6 vols, 1803).

Between 1803 and 1809, Hays lived independently in her own residences and used her private rooms to compose works of fiction and history: Harry Clinton (1804), Historical Dialogues for Young Persons (1806–08), and more. These works were designed by Hays for young and adolescent readers.

Later, after a four-year drought of publications during her residence with her brother Thomas in Wandsworth, Hays departed London. She first took a room in a female boarding school in Northamptonshire and then adopted more elegant quarters in the large town home of the former Bluestocking Penelope Pennington at the Hot Wells in Bristol. Hays produced two didactic works while in Bristol—The Brothers (1815) and Family Annals, or The Sisters (1817)—both aimed at improving the character and prudence of adolescent and young adult readers from England’s emerging working class. Upon her return to London, Hays lived for a time with her brothers and her sister before taking rooms with a Dissenting family in Peckham. In 1819 she returned to central London, to again live with Ann Cole in her new house in Pentonville, from which Hays produced her last known publication, Memoirs of Queens (1821).

From the mid-1780s through the early 1840s, Hays used her private rooms not only to read, research, and compose works for the general reading public, especially young women readers, but also to teach and mentor young females. Hays’s activities as a teacher and mentor were complemented by her decision to board at schools primarily operated by women, including an establishment housed in Vanbrugh Castle, Greenwich. Within three years of her arrival, the Castle was surrounded by the Hays family. During this time, she continued to compose in her private rooms, sending an essay on female education to Eliza Fenwick in New York in 1828 for publication in America. Whether it was ever published is not known.

Hays’s many residences were not romantic getaways for solitude and withdrawal from the activities of life, but rather sites of intellectual engagement and social activity, enabling her to disseminate her ideas through a greater variety of genres and human interactions than Austen’s circumstances and health allowed. Between 1784 and 1821, Hays published poems, religious tracts, essays, novels, life writings, histories, a drama, didactic novels, and educational works for young readers, all designed to inspire and transform the ideals and lives of her audience. Austen’s brilliance in depicting the nuances of human nature in her novels has delighted readers and critics for more than two centuries. Hays’s desire was primarily to “instruct” her readers. In the process, she created a body of work from within the confines of her many “rooms” that not only deserves serious consideration, but suggests many avenues for re-evaluating the nature and extent of women’s active engagement with the female life of the mind between 1780 and 1840.

For more on Hays, visit Dr. Whelan’s website.

Timothy Whelan is a professor of English at Georgia Southern University. He has published widely in British Romanticism and Religious Dissent, especially women writers and booksellers. He was the general editor of an eight-volume edition (Pickering & Chatto, 2011) of the complete works of Mary Steele, Mary Scott, and the nearly 20 women affiliated with the Steele Circle.