If your spirit hears not

If you agree or not

I am

The answer you’ve been searching for centuries…

Towards the gate to a new history…

In the thousand-tongued fire of my glance

I shall burn

The burden of your rusted ideas

Of many centuries.

—Arambam Ongbi Memchoubi, indigenous Manipuri poet

In the summer of 2008, I accompanied Manipuri woman community leader, Ima Lourembam Nganbi, to visit the home of Thangjam Manorama. (TW: sexual assault, torture, and gender-motivated violence.)

The humble mud house had a little veranda where Manoroma's weaving loom stood. The same loom she had used to stitch clothes to feed her elderly mother and send her two younger brothers to school. A photo of her hung over the entry door. Thangjam Manorama was no more, but her name had become etched in the memory of every Manipuri.

Manipur, formerly an independent Asiatic nation-state with a 2,000-year-old history, is located in Northeast India. Bordering Myanmar, it is home to 2.2. million indigenous people. On July 10, 2004, members of the Indian paramilitary unit, the 17th Assam Rifles, came to the house of the 31-year-old indigenous woman, Thangjam Manorama, around midnight.

According to one of her brothers, they surrounded the house and tortured her in front of her mother and siblings, then took her away. Her body was found several hours later on the morning of July 11, 2004, with several gunshots and marks that demonstrated signs of sexual assault and torture. Sixteen shots had been fired at her private parts to destroy evidence of rape.

Following the incident, protests erupted all over Manipur, and 12 Manipuri mothers staged one of the most extraordinary demonstrations ever seen in the history of the region. They stripped off their clothes in front of the gate where the paramilitary troops were stationed, and unfurled a banner stating, “Indian Army Come and Rape Us. We are all Thangjam Manorama’s Mothers.” According to Paromita Chakravarti, a professor of women’s studies, the protest “commanded awe because it deployed the trope of motherhood to shock and shame the army…they turned the shame of rape back on Manorama’s rapists.”

I grew up in Manipur in an atmosphere where the struggle for gender justice was always present. Whether it was the protest against Manorama’s killing or the thousands of lives lost during the 50 years of military occupation by India. For us Manipuri women, the fight for gender justice has been a fight for our survival.

The Body as a Weapon: Indigenous Women’s Resistance Against Martial Law

Since 1958, though unrecognized by the world, the Indian government has imposed a martial law called the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) on indigenous people who live in the regions of Northeast India, including Manipur. In addition, the history of 45 million indigenous people has been deleted from the curriculum of modern India, and rampant racism continues against the indigenous people living in Manipur and Northeast India to this day. To protest the violation of their rights, women throughout Manipur have held sit-ins and protest marches. In the 1980s, some of the women started a movement called Meira Paibi through which they stayed out all night and patrolled the streets with flaming torches. Irom Sharmila protested the martial law through a 16-year hunger strike, known to be the world’s longest hunger strike. The Indian state dealt harshly with the various protests. Irom Sharmila’s hunger strike was classified as a criminal act; she was confined in a hospital for 16 years and force-fed rice, lentils, and water thrice a day. The government of India also imposed the National Security Act on the mothers of Manipur who protested nude against the Indian paramilitary following the rape and killing of Thangjam Manorama in 2004.

In spite of the politics of death in Manipur, the Meira Paibis have been at the forefront of a strong nonviolent peace and resistance movement ever since counter-insurgency operations began to take place in the late 1970s.

The Nupi Lan (Women’s War) Movement of Manipur

The extraordinary movement of Manipuri women has its origins in history. In 1891, Manipur came under British suzerainty, and the anti-colonial protests that followed led to the burning down of two bungalows of British officials. In order to rebuild these houses, Colonel John Maxwell reintroduced a forced-labour measure known as the Lallup System. Under this measure, Manipuri men were obliged to provide free labour for 10 days after every 30 days of paid work. It was in response to this order, in 1904, that the first Nupi Lan (Women’s War) broke out. By this point, women had become used to taking the reins in society, whether politically, socially, or economically. To fight this measure, they protested the colonial administration by conducting demonstrations in public spaces, including the historic women-run trading market Nupi Keithel, stirring public outrage and encouraging women from across the state to join the movement.

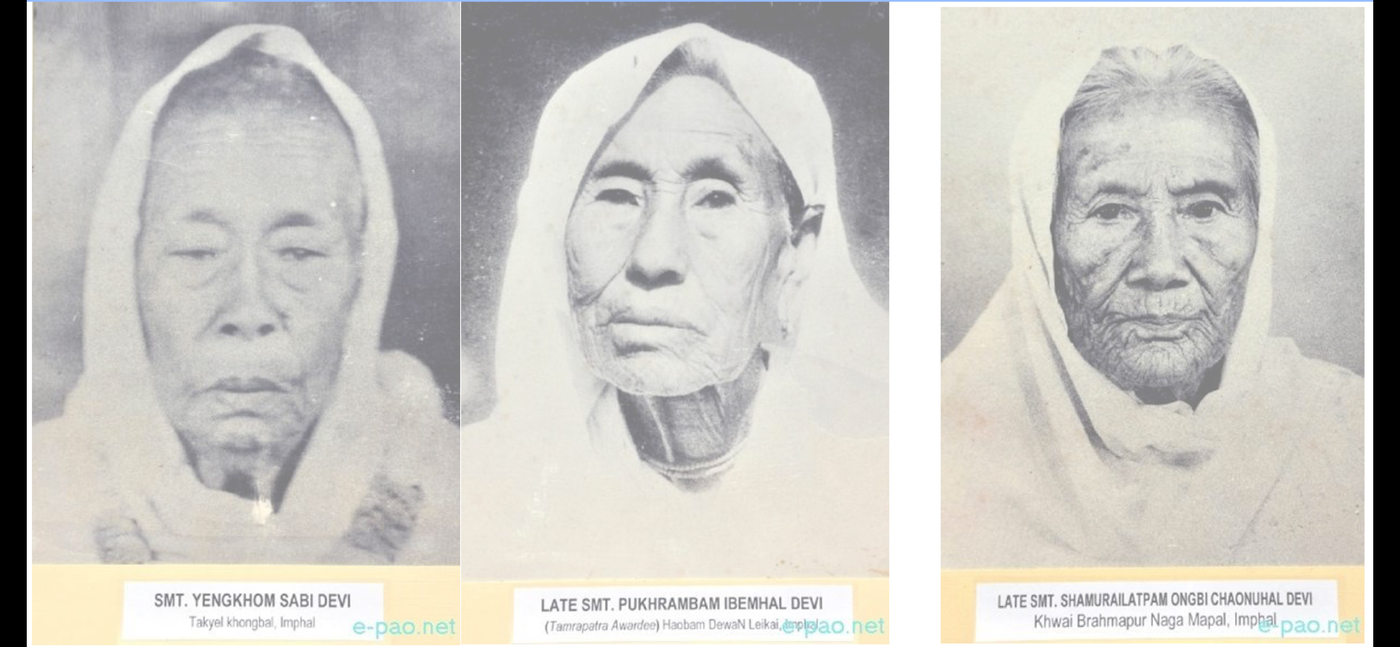

In September of 1904, thousands of women rallied together and marched toward the British colonel’s residence. When the administration stated that it would reconsider its decision, the women were not satisfied. Refusing to give up, 5,000 women gathered at Nupi Keithel to protest the colonel until he revoked the order. The demonstrations eventually turned violent, and the women were dispersed using force. Still, their cries in unison led to the removal of the Lallup System, and planted the seeds for widespread political consciousness in future generations of women.

The Second Nupi Lan: 1939

In 1907, the administration of Manipur was handed to Raja Churachand Singh and his durbar (governing body) yet the British continued to hold considerable power in determining regional trade and economic policy. Excessive rains, closings of rice mills, and the increased export of rice from Manipur to outstation British battalions, resulting in a man-made famine, led to widespread uprisings and protests. On December 12, 1939, thousands of women marched to the durbar’s office to demand a ban on rice exports and to reopen the rice mills. Hearing that the Maharaja was out of town who had the power to authorise their demands, the women held the president of the durbar captive and insisted that he send a telegram to the Maharaja. By then, nearly 4,000 women had camped outside the office, refusing to leave until they got what they wanted.

In an attempt to diffuse the situation, Assam Rifles soldiers were brought in to disperse the women. Nupi Keithel was shut down for almost 14 months. The British administration even tried to sell the marketplace to foreigners, but the women fought hard to prevent that from happening. The Manipuri women were undeterred; they continued to stage demonstrations and protested against traders and the local rulers. Eventually, a ban on the export of rice was put into place. To commemorate the resilience and grit of these women, December 12th is celebrated every year in Manipur in honour of the second Nupi Lan. A statue in the middle of Imphal, the capital of Manipur, marks this momentous struggle.

Since then, Manipuri women have stood at the forefront of countless protests in the state, including the Meira Paibi movement that emerged in the 1970s, and later, in 2004, when 12 mothers waged a ‘bare-body’ protest against the gang-rape and murder of Thangjam Manorama and called for the revocation of the AFSPA.

The bare-body Manipuri mothers created a state of emergency to force onlookers to recognize the state of exception for what it was. Their demonstration marked not only a new mode of women’s resistance, which redefined rape and rewrote the semiotics of the nude female body, but also pointed toward new ways of resisting decades of violence against the native people of Manipur.

As the women of Manipur demonstrated, their bare bodies are their agency and no military or government should touch their bodies—including in policy and planning. Resistance by indigenous women calls attention to the resilience of human life and the persistent struggle for a gender-just and gender-equal world.

Binalakshmi “Bina” Nepram is the founder-director of Manipur Women Gun Survivors Network and convener of Global Alliance of Indigenous Peoples, Gender Justice and Peace. She received the Dalai Lama Foundation’s WISCOMP Scholar of Peace Fellowship in 2008 and has represented Indian civil society in meetings of the United Nations in Geneva and New York. She is the author of five books, most recently Deepening Democracy, Diversity and Women's Rights in India (2019).