Every New Historia Schema, says Jamer Hunt, our “poetical scientist” and Director of Design/Content, is like a teabag of distilled information produced by a New Historian who is an authority about the individual woman within the context of her time and place. Schemas look daunting because they may refer to individuals in cultures far removed from us geographically and historically. But, like the most sumptuous teas, when refreshed by boiling water -- to stretch the comparison -- when we pay attention to the details that are provided, the schemas open up to reveal the life of a particular woman, emphasizing what can be documented about her experiences, contributions, strategies, and transformations within the context of persistent historical misogyny.

Family Background

Lysimache lived in Athens in the fifth-fourth centuries BCE. She came from a noble family which accorded her high status in Athens and enabled her to take up the most important priesthood in the city as priestess of Athena Polias at the age of twenty-four, a role she held for a remarkable sixty-four years.

Cultural Significance

Lysimache was a woman of great cultural significance. That we know anything about her life is in itself exceptional for a woman at this time. When we look at people’s names that have survived in the textual or archaeological record from ancient Athens, we find we have ten men for every woman, and few of the women whose names have been remembered have significant biographical information recorded about them. While this has been taken to mean that women had no role to play in public life, the opposite is actually true. Historians, both ancient and modern have generally regarded women, even those of high status, as neither seeking nor playing any significant public role. However, this neglects the evidence we have of the importance of women in religion. Religion was a vital part of everyday life in classical Athens and women played significant roles in both private and public religious activities. Lysimache was one such woman and was publicly honoured for her contribution to Athens.

The priesthood Lysimache held was believed to have been vital to the life of the city-state of Athens. The relationship between the Athenians and their gods was considered so important that they invested a great deal of their resources in grand buildings for their gods, in statues as media of their gods’ epiphanies, and in the festivals they celebrated in honour of them. The Athenian government’s primary duty was to oversee the proper performance of the city’s cult activity. Indeed, the wellbeing of the city and its citizens was believed to be dependent on the good will of the gods, and this could only be secured by proper cult practice managed by its priests. The most important priesthood in the city of Athens was the one dedicated to the protective deity of the city, Athena Polias, and the highest priestly office was the office of her priestess. This office was held by Lysimache for a remarkable sixty-four years.

Reputation

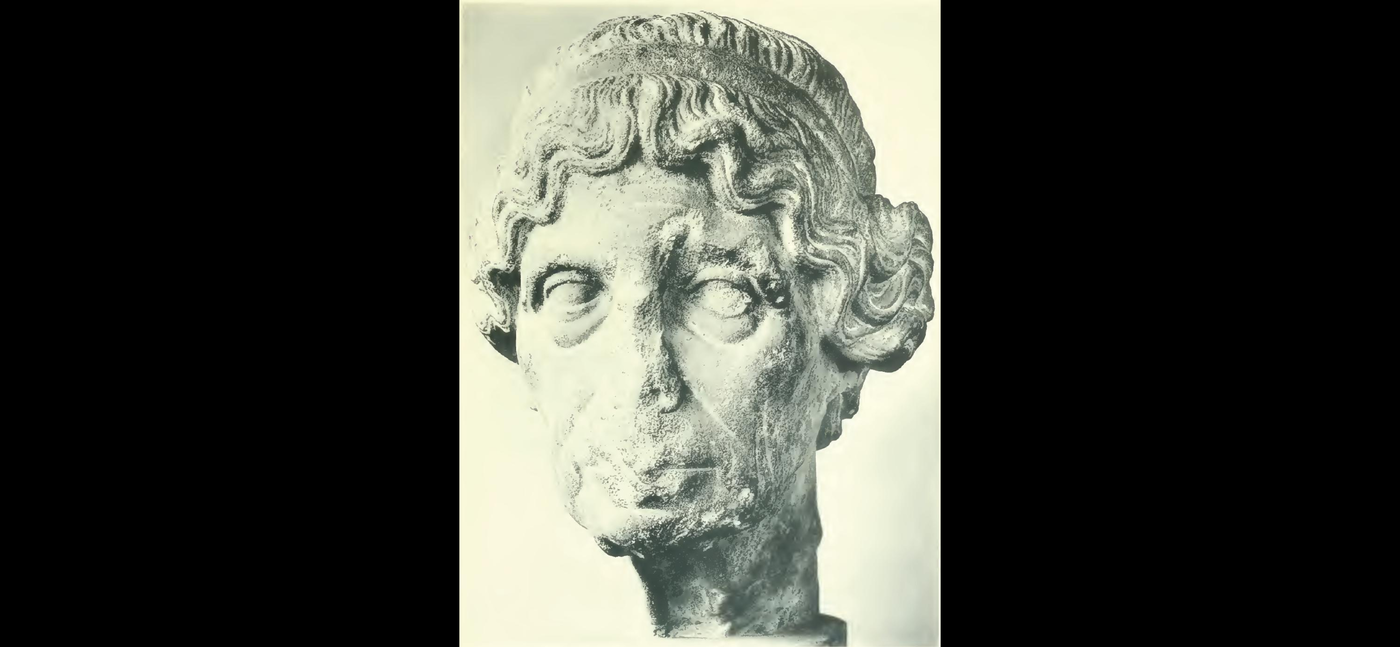

While we do not have a record of particular actions she may have taken, we do know that as the priestess of Athena Polias Lysimache established such a positive reputation for herself that the city determined to honour her publicly. We know that Lysimache saw the city through one of the most turbulent times in its history. During her time as priestess, Athens suffered a devastating plague, lost its empire in a costly and tragic war and saw its democratic government toppled. Divine anger, which was believed to be behind such adversity, could only be averted by the restoration of divine approval through proper cult worship, hence the particular importance of the city’s priests at that time. It was Lysimache who led Athens spiritually through a period of crisis to the point where it emerged again as a prosperous city, its democracy restored and empire regained. She was of such central importance that she was celebrated after her death by the people of Athens. They erected a statue of Lysimache on the Acropolis, the seat of the worship of the Athena, the first public acknowledgement of the achievements of a priestess in Athens that we know.

Controversy: Social Activism

Evidence of Lysimache’s reputation and the esteem with which she was held in Athens comes in the comedy of a contemporary playwright, Aristophanes. He represents her in the guise of Lysistrata, the central character in his play of the same name. Here she appears as a social and political activist, the leader of the Athenian women who seize the Acropolis and force the Athenians to bring an end to their war. Moreover, she successfully encourages women from throughout Greece to break out of their normal social roles and to confront and overcome male aggression.

In a second play, Aristophanes has his protagonist pray to the goddess Peace, calling on her to be ‘a true Lysimache’. In this play advocating the end of a war that had already run for nearly ten years, naming Lysimache and associating her with the idea of peace ties her publicly to a political position, something extraordinary and controversial for a woman at this time.

It is quite possible that Lysimache herself was at the performance of both of these comedies, and sitting prominently in a seat of honour. Scholarship dating back to eighteenth century Germany wants to exclude women from attending the theatre in Athens on social and political grounds. However, that position arises from a lack of direct evidence from the fifth century. Instead, we do know that the religious festivals in which tragedies and comedies were performed did include participation by women so there is no compelling reason to conclude they did not also attend the dramas. The priestesses after Lysimache’s time certainly did. Seats inscribed with the names of priestesses have survived in the Theatre of Dionysos from a later period and, given the conservative nature of religious ritual, this probably reflects the practice in Lysimache’s day too.

Controversy: modern reception

Yet, despite the central role of religion in the life of the city and Lysimache’s personal importance in classical Athens, her contribution to the life and wellbeing of the city has not been well acknowledged by historians. The names of women who held honoured positions like Lysimache rarely even made the record of historians in their own day. The ancient male historians focused their attention on the male pursuits of politics and war, a practice repeated by the modern scholars who followed them. In addition, in focussing on the comic side of Lysistrata’s actions in Aristophanes, modern critics have devalued the strong humanitarian message delivered in her name. That the audience should recognise Lysimache in this character testifies to her reputation both as a strong female leader and as a woman who stood for peace.

Dr Ian Plant, author of Women Writers of Ancient Greece and Rome: An Anthology (London: Equinox, 2004), is a New Historian who is uniquely qualified to explain how to read the schema he produced for Lysimache. Dr Plant’s anthology identifies and brings together, with his own new translations, the extant fragments of the works of female writers from the Greco-Roman world. It includes works attributed to women that cover a wide range of genres, including poetry, history, philosophy, musical theory, grammar, literary criticism, astronomy, travel, medicine, sex, mathematics, drama, prophecy, and alchemy. The anthology demonstrates that, while only about one hundred female authors can be identified among the over four thousand attested Greek and Latin authors, the work attributed to women reveals an engagement with knowledge and knowledge creation that went much deeper than the (male) scholars of the time and later historians have previously acknowledged.