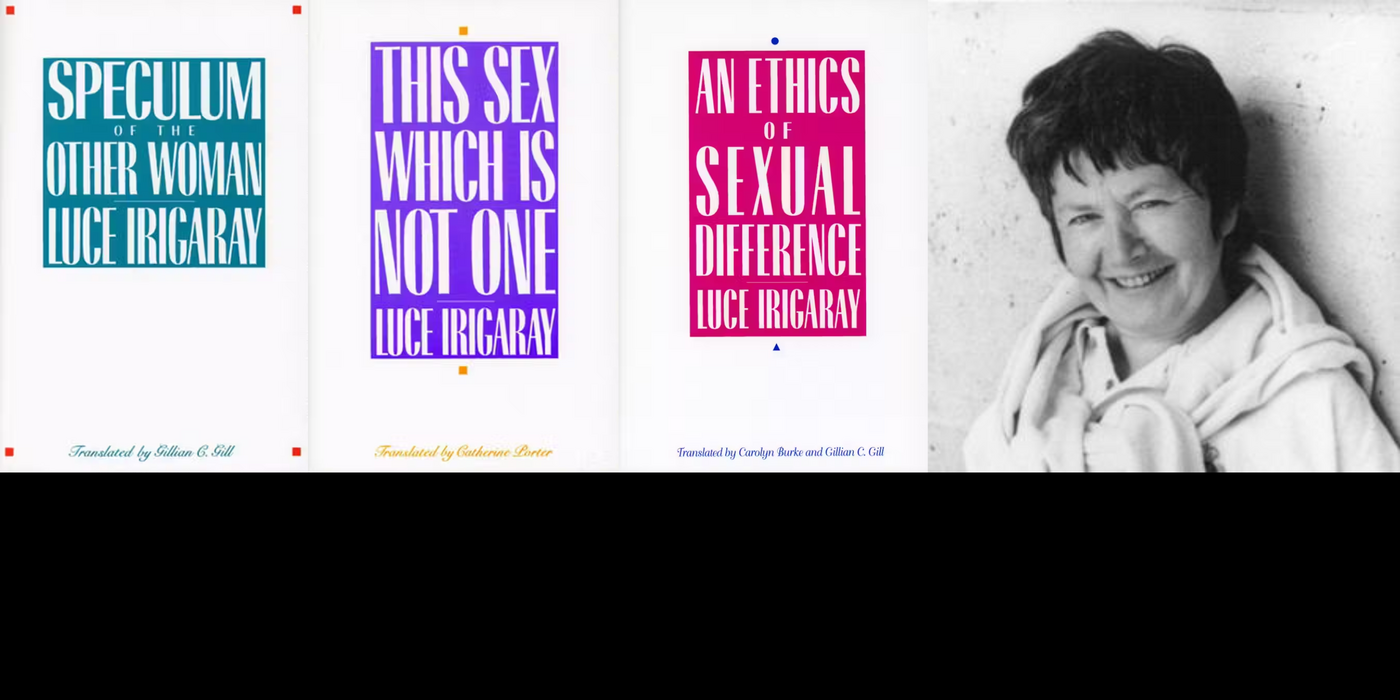

Luce Irigaray (1930– ) studied at the University of Paris during the heady period of the 1960s. She gained a doctorate in linguistics in 1968, trained as a psychoanalyst with Lacan’s École Freudienne de Paris, and completed a second doctorate in philosophy in 1974. Her thesis became the book Speculum of the Other Woman, which put forward a radical feminist critique of the patriarchal "symbolic order." It was too radical for the Lacanians. She was expelled from the École Freudienne and dismissed from the teaching post she held at the time.

Speculum starts with a detailed critique of Freud's ideas on women. Irigaray challenges his accounts of “penis envy” and female hysteria, and his treatment of the Oedipus complex as the foundation of civilization. She documents how Freud equates the phallus with symbolic power, reducing women to mere reflections of men, defined by what they lack. He marginalises the mother-daughter relationship in favour of the father-son bond.

As a result, only the masculine has a place in the symbolic order of law and culture, while the feminine is relegated to silence and absence.

Irigaray traces the roots of these Freudian ideas in the history of Western philosophy. Examining Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, Descartes, Kant, and Hegel, she reveals a recurring pattern to portray women as negative spaces–absent, silent, or the opposite of men. In the book’s final part, Irigaray analyses Plato’s myth of the cave. She argues that the cave, representing ignorance and transient material reality, is modelled on the female body; this associates the female body with change and unreason, what we have to transcend in order to reach the light of truth, reason, and reality.

Irigaray concludes that the whole of Western philosophy and culture has historically been spoken from a masculine perspective. There has only been one speaking subject in Western thought–the male subject–while women’s voices, desires, and identities have been suppressed and misrepresented.

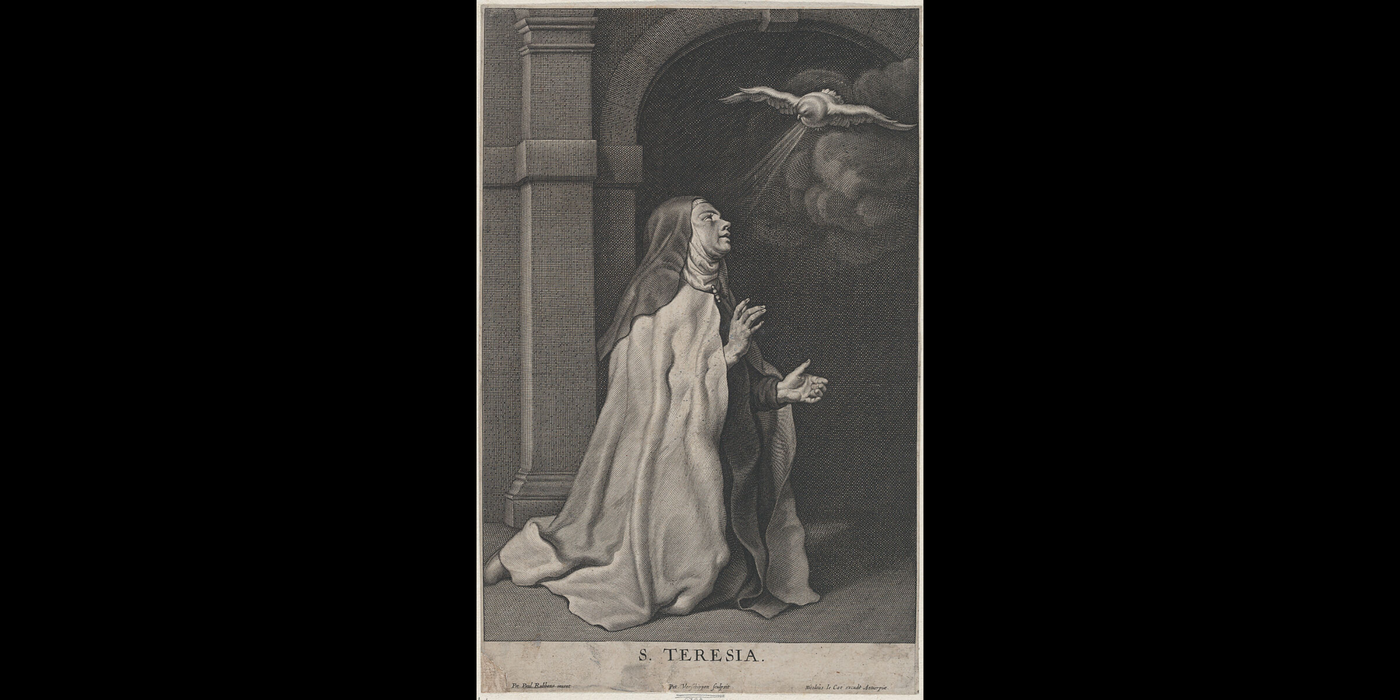

She offers one striking exception: the medieval women mystics, such as Teresa of Ávila, discussed in the chapter La mystérique, which is right at the middle of Speculum. However, Irigaray sees the women mystics not as thinking and doing philosophy, but speaking from a place outside reason and consciousness–expressing passion and confusion, rather than rational discourse. Women such as Teresa could speak only by inhabiting the place of irrational Other to which philosophy had consigned them.

In her writings after Speculum, Irigaray called for the creation of a feminine subjectivity. She wanted women to articulate their own perspectives and develop their own voices, not by adapting to the male-dominated order, but through a radical cultural transformation. The task was not to recognise any existing perspectives and values of women, for these had been comprehensively suppressed. Instead, the agenda was to build an entirely new vantage-point in language, thought, and culture: a feminine subject-position. This had no precedent in Western culture, although rare glimpses of a feminine subjectivity could be glimpsed in pre-historic myths, like Demeter and Persephone, or occasional artistic images of the Virgin Mary with her mother, Anne.

When I first read Irigaray’s work as a PhD student in the 1990s, I found these ideas thrilling. Philosophy was even more male-dominated then than now, and Irigaray’s insistence that women must find their own voices was energising and inspiring. She was not relinquishing philosophy to men but reshaping it on her own terms.

Returning to Irigaray today, however, there are problems with her views. Referring to the medieval mystics in Speculum, she claimed: “This is the only place in the history of the West in which woman speaks and acts so publicly.” With the benefit of fifty years of feminist scholarship–and projects like The New Historia–we now know this is not true. Women have spoken and acted publicly throughout history; the real scandal is how thoroughly their contributions have been erased from the historical record.

The problem has never been that women didn’t speak, but that their words have been systematically excluded from historiography.

Similar concerns arise with Irigaray’s argument about the mother-daughter relationship. She suggests that mothers have been reduced to mere biological figures, from whom daughters have to break away to enter language and culture. Her solution was for women to have symbolic, intellectual mothers–foremothers and role models–so they could participate in culture as women and not surrogate men.

I absolutely agree that we need these foremothers. Indeed, I used to see Irigaray as my own “philosophical mother.” But I disagree with her claim that these intellectual mother-daughter relationships have never existed before. History is full of women forming intellectual lineages. For instance, the Victorian feminist philosopher Frances Power Cobbe dedicated her Essays on the Pursuits of Women to three foremothers–scientist Mary Somerville, sculptor Harriet Hosmer, and educational reformer Mary Carpenter–representing the pursuit of truth, beauty, and goodness. Similarly, Harriet Martineau’s first published essay was on Hannah More and Anna Barbauld. She aspired to follow in their literary footsteps, describing Barbauld as a “forceful and elegant” writer and setting out to be precisely the same kind of writer herself.

In some ways, Irigaray’s work unintentionally adds to the erasure of these women by exaggerating the total dominance of masculine subjectivity. Yet at the same time, she highlights something crucial: that feminine subjectivity relies on networks of intellectual women supporting and inspiring each other. And if it is possible to create a feminine subjectivity today–as she proposes–then surely it must have been possible before as well. Women have always been thinking, speaking, and forming intellectual alliances, even though mainstream historiography has usually written them out. Irigaray’s vision can continue to inspire us, not only to imagine new possibilities, but just as importantly to uncover the past histories of women’s thought and networks.

Alison Stone is Professor of Philosophy at Lancaster University. Her most recent books are Women Philosophers in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Oxford University Press, 2023), Nineteenth-Century Women Philosophers in Britain and America (co-ed with Charlotte Alderwick, Routledge, 2024), and Women on Philosophy of Art: Britain 1770-1900 (Oxford University Press, 2024). With Lydia Moland, she is co-editing the forthcoming Oxford Handbook of American and British Women Philosophers in the Nineteenth Century. See https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/ppr/people/alison-stone