“Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, may be refin’d and join th’angelic train” -Phillis Wheatley, On Being Brought From Africa to America, 1773

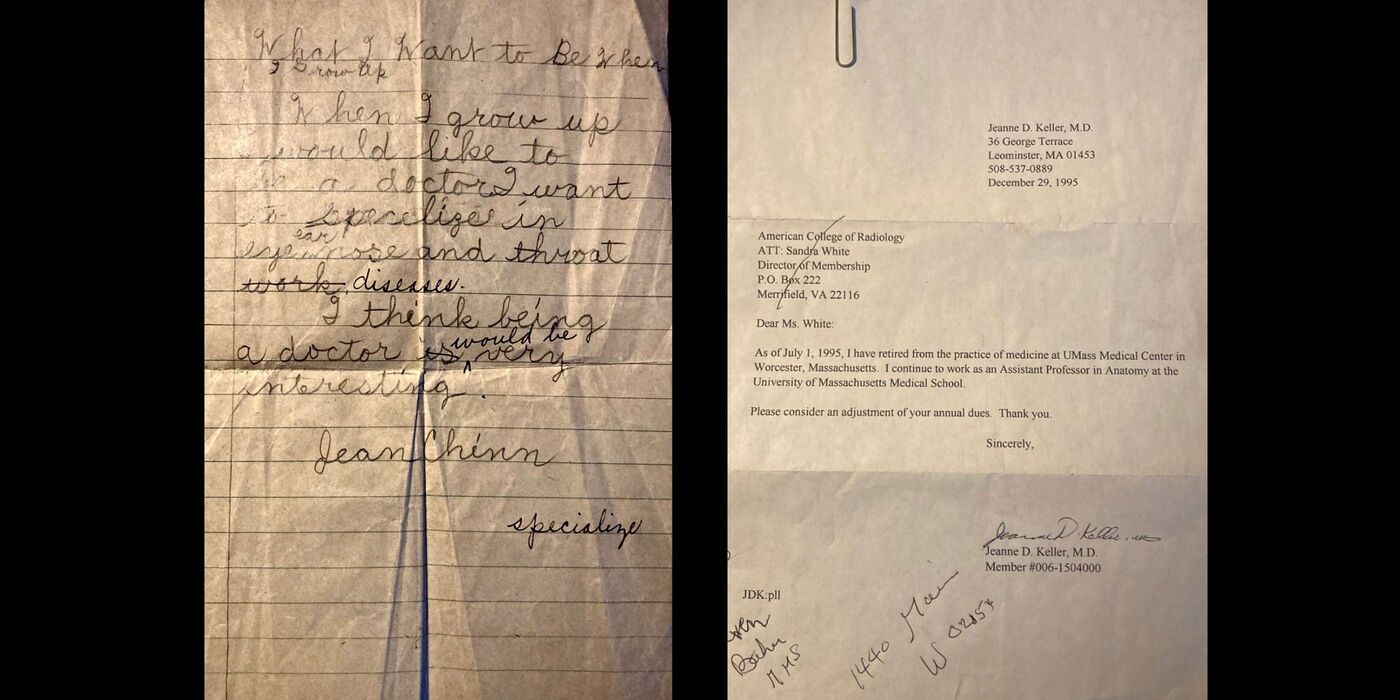

In a town in West Virginia, likely on a tobacco plantation, a little Black boy and girl learned to write. One was born a slave. The other’s origins are a mystery. Despite the pre-disposed restrictions of being Black, they learned. They simply did. The act of doing is one of complexity, especially in a misogynistic society where, from the time of my grandmother's birth and till her death, women's autonomy was consistently growing and receding, again and again. The story of these children from West Virginia who learned, against the odds, to write, is the story of my first free ancestors, the Lomaxes. I am curious about the women who did, about the women who were able to learn and take action in the world despite their circumstances, regardless of the consequences. My grandmother was one of these women.

***

Jeanne Delores Keller was born May 7th, 1930, in Harlem, New York, where she spent her childhood in an apartment above her father’s medical clinic. She was a Black woman, she was my grandmother, and it is believed that at the age of two, Jeanne first expressed her desire to become a doctor, a desire that would guide the course of her life.

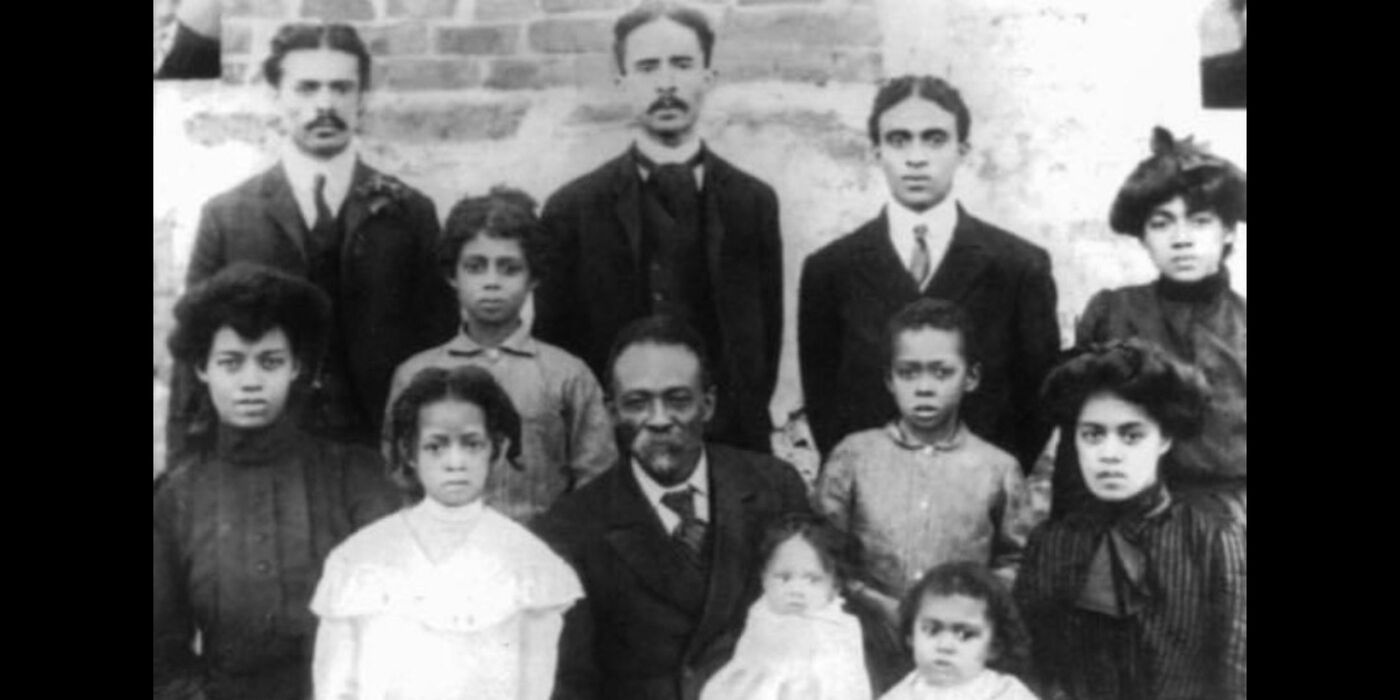

She was born to Chester Wellington Chin and Lucille Genevieve Lomax. Her father was the first triple-boarded physician in the United States, Black or White. He received his degree from Columbia University and was a member of the African American fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha. Her mother was a glamorous homemaker with an extensive fashion collection and charisma to her, as many in my family have described. Her hair was always well done, courtesy of Jackie Onassis’s hairdresser, and she was a master's degree holder from Howard college, where she graduated in the late 1920s.

My grandmother’s life came to resemble that of both her parents. After attending the Little Red Schoolhouse, a progessive school in Greenwich Village, for much of her childhood, Jeanne moved to Malba, Queens with her family. Her mother, who had a lighter complexion and passed for White, purchased the family’s new home. After Jeanne’s family moved in, the local White and wealthy neighbors expressed discontent with the new inhabitants, but Jeanne’s father, my great-great grandfather, was a highly respected physician and is believed to have spoken to Mayor LaGuardia, who quelled the neighborhood outrage.

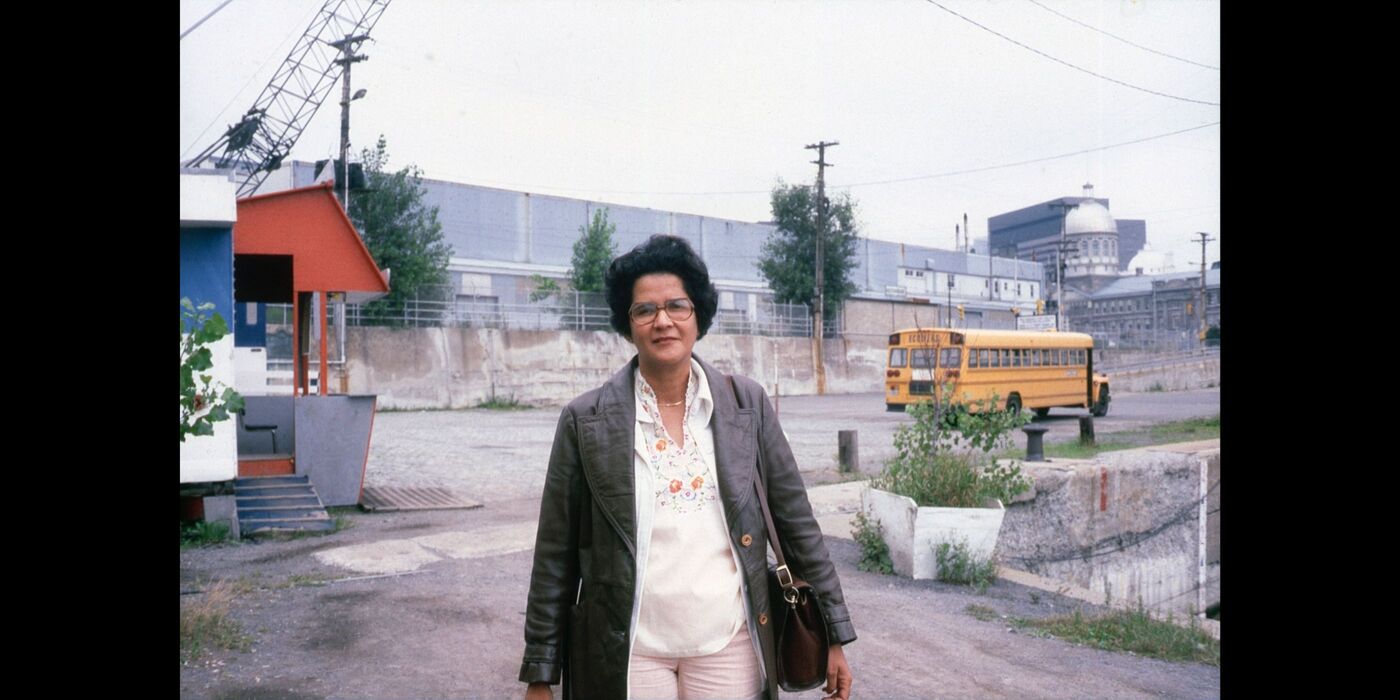

As an adolescent, Jeanne skipped multiple grades and spent her high school years attending Hunter College High School, where she was popular among her peers. Over the years, her relationship with her father remained strong– likely a key influence in Jeanne’s pursuit of medicine. After high school, Jeanne enrolled in Radcliffe College, an independent women's institution now a part of Harvard University, to pursue a degree in Anthropology, graduating in 1951. She studied medicine at Boston College Medical School, where she quickly became engaged to one of her classmates. After her graduation, her fiance attended Yale, and she began residency at Cambridge City Hospital, where amidst the hectic life of residency, she met Dieter Keller, a fellow resident. They were fast friends and spent the following years cycling together and adventuring around Massachusetts.

After her residency, like her father before her, Jeanne journeyed to Germany to complete additional training. After her move, her friend Dieter was distraught. He followed her to Germany and pleaded for her hand in marriage, to which she replied yes. Her previous engagement was broken off, and she married Dieter, my grandfather, in Frankfurt, Germany, where just a few decades before his family had fled from Jewish persecution before World War II.

Back in the United States, Dieter’s parents were shocked to discover Jeanne was a Black woman from a Black family. Their priest told them the couple's children would come out “striped and polka dotted,” and the parents demanded that the marriage be annulled. They drove to my great grandparent's house to make their demands known, likely expecting a scene different from the elegant homemaker, successful physician, and large house overlooking the river in Malba, Queens that they found. The marriage was, of course, not annulled.

Finally, my grandmother moved on from residency to become a doctor of radiology, a specialty which allowed her to pursue her love of medicine, and of motherhood, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The couple had five children, three of whom pursued work in the medical field. While raising her five children, she went on to publish a medical textbook, Basics of Head and Neck Film Interpretation. In the dedication, she thanked her family. In all of these accomplishments, without meaning to, Jeanne became a trailblazer–not only for women but for Black people as well.

***

In conducting this project, I felt a unique sense of privilege in being able to learn so much about my grandmother. Many Black and mixed-race children do not have the luxury of knowing their ancestors or genealogy, as too often these stories are hidden or destroyed. It never occurred to me growing up that my grandmother was a trailblazer, she was just Oma, my biggest cheerleader. Recovering her story has reignited my dedication to uncovering women’s history and inspires me to aim for the same level of accomplishment and respect she earned. This historical recovery is a love letter to the woman who formed my family, the woman who gave me a deeper understanding of who I am and who I want to be.

Jesselyn Putney is currently earning her undergraduate degree in History and Gender Studies at The New School. She has a developed interest in African American history, particularly in regards to Black women's studies, as well as an interest in the history of sexual minorities. Her entry on her grandmother was a project of love.