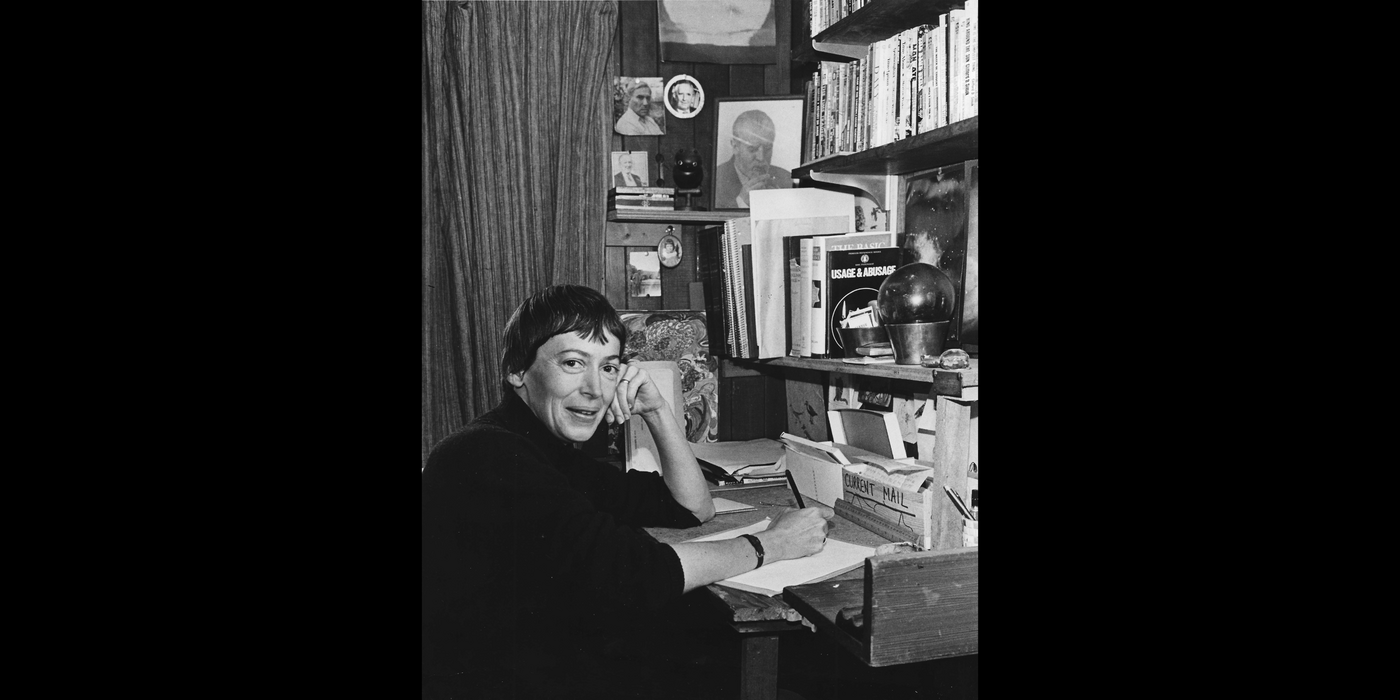

It doesn’t have to be the way it is. This is the title of a chapter in Ursula Le Guin’s book No Time to Spare (2017) in which she discusses the boundaries of imaginative literature, including fantasy fiction, her specialty. The fantastic tale, she explains, may be at odds with the laws of physics or probability in some ways–carpets may fly, or a child adrift at sea may be rescued by a mariner–but this “revolt against reality” has limits. The writer of fantasy fiction still operates within some confines. Causal relations still exist: because a certain event, A, occurred, another event, B, occurred, even if the reader learns about event B before learning about event A. Spatial relations, too, still exist: someone was here, now she’s there, even if the way of getting from here to there is extraordinary. Fantasy fiction is not a case of “anything goes.” “Anything goes” is irresponsible; it makes the narrative incoherent.

But for all that, Le Guin insists that fantasy fiction does invite the reader to consider the nature of contingency: some things don’t have to be the way they are. Yes, causal relations must be as they are, whether in a fantasy world or the actual world, but what about gender relations? Could they be different in a fantasy world? Yes. Then why not in the actual world? Once we make that inference, once we open our minds to that question and others like it, then the claim “it doesn’t have to be the way it is” is no longer a playful statement, made in the context of fiction, but a subversive statement, made in the context of the actual.

Philosophers–like myself–are akin to fantasy writers in that we absolutely believe that things don’t have to be the way they are, and we often craft thought experiments to show how they might be instead. For example, John Rawls asks what principles of justice and fairness we might come up with if our decisions about social arrangements were made from behind a “veil of ignorance”–that is, from a position that conceals from each of us what our own characteristics, circumstances, and societal position (gender, race, class, social status, wealth) might be. Or, what might we learn about our ideas of reality and knowledge by imagining ourselves as brains in a vat of nutrients being fed stimuli that mimics what we would experience if we were not brains in a vat (a 20th-century update of Descartes’ 17th-century claim that we might be in a perpetual dream state)? The point of these thought experiments is to shake us up–to turn what is familiar and seemingly unassailable into an object of inquiry.

As feminists, I think the lesson we learn from Le Guin’s reflections on fantasy fiction and from the method of thought experimentation that philosophers use is that the status of women does not have to be what it is. It could be different, and we can make it different. It doesn’t have to be the case that a woman’s claim that she is the victim of domestic violence is denied or ignored until a video of the attack is made public, though too late for charges to be filed (due to a statute of limitations). Instead, acts of violence against women and girls could be thought so heinous, so unacceptable to the social order that a perpetrator of such violence is censured and condemned by all. It could be that the wage gap between women and men has not merely narrowed (barely!) over a 20-year period (as was the case between 2003 and 2024) but been totally eradicated. It could be that the intelligence, competence, and savvy of women seeking political office is valued and acknowledged, and even taken for granted.

It doesn’t have to be the way it is. Let’s not let misogynists tell us it does.

Nancy Kendrick is Emerita Professor of Philosophy at Wheaton College, Norton, MA, and Philosopher-in-Residence at the New Historia.