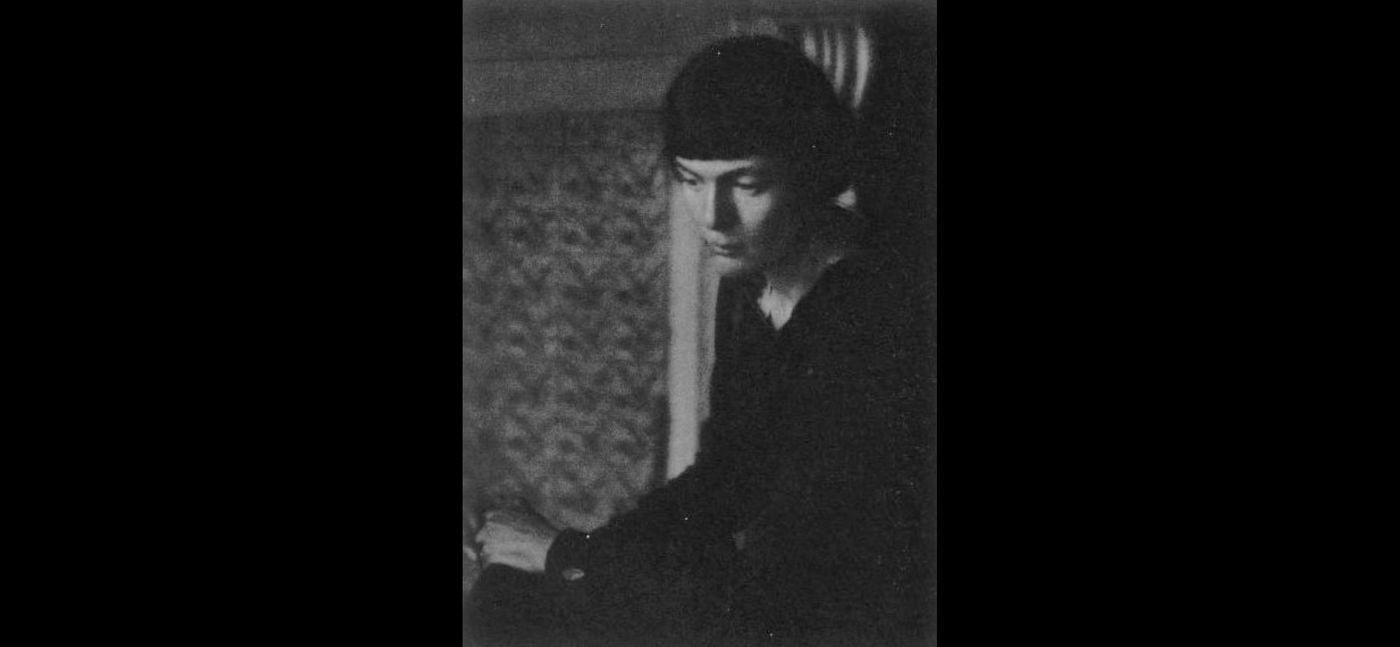

It is a lamentable truth that we know relatively little about women’s lives and work in antiquity, but we do have plenty of artistic and philosophical portrayals of female figures, which offer insights into the cultural values and practices of ancient Greece and Rome. As a classicist, I’m interested in conceptions and representations of women in ancient literature and in their reception throughout history, particularly by women. The prolific American poet Hilda Doolittle, known as H.D. (1886–1961), drew heavily on Greek mythology in her work yet gets surprisingly little recognition or treatment in the field of classics.

H.D. was engaged in the same sort of imaginative feminist recovery we see in recent translations of the classics by women, including Emily Wilson’s groundbreaking version of the Odyssey and Shadi Bartsch’s Aeneid, and two forthcoming translations of the Metamorphoses by Stephanie McCarter and Jhumpa Lahiri. The past few years have also seen a proliferation of literary rewritings of mythological stories originally penned by men, including Madeleine Miller’s Circe, Natalie Haynes’s A Thousand Ships, Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls and The Women of Troy, and Nina MacLaughlin’s Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung.

Creative works like these remind us that there is more than one way to tell a story and that multiple voices can get lost in the telling.

Wilson is acclaimed for her new renderings of Greek words that have been translated by men in ways that are less sympathetic to female characters, and McCarter has spoken about how her translation of Ovid’s text will revise male translators’ euphemistic or neutral wording of scenes involving sexual violence. In their novels, Miller, Haynes, Barker, and McLaughlin grant agency to female characters we know only tangentially or through the eyes of men, allowing them to speak for themselves.

My interest in H.D. was sparked by a chapter devoted to her in Francesca Wade’s Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars. Poring over H.D.’s Collected Poems, I was struck not only by the breadth of her work but also by the number of poems written from the perspective of mythological women. Her poems quite literally give voices to women who are marginalized in the larger stories of men’s exploits.

Many of the narrators—mothers, daughters, lovers; goddesses, mortals, and in-between; both named and anonymous—are in states of grief or distress. H.D. sympathized with these women. Her first child, a girl, was stillborn, creating “a sort of black hollow” within her, and two years later her husband started an affair with their friend Arabella Yorke, telling Hilda, “I would give her a mind, I would give you a body,” suggesting that the two cannot coexist in a single woman. Expressing the grief of women in the ancient texts she loved proved to be a life-saving mission.

H.D. did not engage with the classics as an academic. As a youth, she attended a prestigious prep school with an egalitarian intellectual spirit, and she graduated fourth in her class, one of only 10 girls in the rigorous Classical Section. Bryn Mawr was similarly progressive in its commitment to offering women a robust education, and she enrolled there as a day student to train as a scientist like her father. She studied Latin and mathematics; her literature grades were too low to allow her to pursue English.

The university proved to be influential less for its academic training and more for its community of like-minded and creative people. Feeling torn between the paths of scientist and artist, H.D. dropped out after three semesters to focus on writing and travel. Instead of translating texts as a class assignment, she copied out Greek to translate with her companions on their travels.

The Greek language and its stories were liberating for H.D., and her relationship to them soon became more generative, as she “translated” the lives of the women she encountered into her own poems: wives and lovers whose men fail them (Eurydice, Ariadne, Penelope), powerful goddesses who harbor feelings for mortals (Calypso, Circe), queens with destructive passions (Phaedra, Helen), mothers who lose their children (Demeter, Thetis), and “mad” women cursed by the gods (Cassandra).

The complicated legacy of the infamous Helen of Sparta was a subject of particular fascination for H.D. She devoted a book-length poem to her called Helen in Egypt. Not only does H.D. reclaim the story of the mythological Helen, but she gives the broader story of the Trojan War political significance by subtly linking it to modern war, “fought for an illusion.”

She also wrote poems for ancient female poets—Nossis, Telesilla, and Sappho—and the subjects of love epigrams by male poets—Heliodora. A little-known poem called “A Dead Priestess Speaks,” narrated in the first person by a fictional priestess named Delia of Miletus, offers a snapshot of an unremarkable but not unhappy or unfulfilled life, in contrast to the storied lives of the other women in the collection: “I never shone/with glory/among women,/and with men,/I stood apart,/smiling;/they thought me good;/...I smiled,/I waited,/I was circumspect;/O never, never, never write that I/missed life or loving;/when the loom/of the three spinning Sisters stops,/and she,/the middle spinner, pauses,/while the last/one with the shears,/cuts off the living thread,/then They may read/the pattern/though you may not,/I, being dead.” It’s a moving, intimate glimpse into the subjectivity of a “regular” ancient woman as imagined by a brilliant modern mind steeped in classical culture.

Though H.D. is best known for her poetry, her often overlooked translations of ancient Greek texts are just as worthy of attention. She was drawn especially to Euripides, whose tragedies are notoriously bleak and brutal. She identified a sense of timelessness in the suffering experienced and expressed by the female characters—the Trojan Women, Medea, Phaedra, Iphigenia—which she was able to link not only to her own personal losses but to the larger devastation of the First World War. The passages she chose to translate focus, in large part, on the female choruses, who offer commentary on the action but cannot directly intervene. H.D. also translated the first 100 lines of the Odyssey, though she has not received credit as one of the few women precursors to Emily Wilson, perhaps because her excerpt is considered too short to matter. H.D. translated many fragments of the Greek lyric poet Sappho, and also built on them to form full poems, interweaving her poetic voice with Sappho’s. The stripped-down quality of the original fragments influenced H.D.’s poetic style, and Sappho’s work encouraged her to experiment with form and grapple with her own struggles with sexuality, desire, creativity, and authorship.

H.D.’s work suggests that feminist historical recovery can take on as many forms as the sea god Proteus. She bestows on her female subjects identity, power, and authenticity. One of the most striking demonstrations is her Eurydice, who doesn’t get a voice of her own in the ancient canon, but who, thanks to H.D., gets a chance to address her husband, Orpheus, speaking as a woman who has experienced great loss but has nevertheless not lost herself, and in fact has found herself anew: “At least I have the flowers of myself,/and my thoughts, no god/can take that;/I have the fervour of myself for a presence/and my own spirit for light;/and my spirit with its loss/knows this;/though small against the black,/small against the formless rocks,/hell must break before I am lost;/before I am lost,/hell must open like a red rose/for the dead to pass.”

Hilary Ilkay holds a B.A. in classics from The University of King’s College and Dalhousie University and an M.A. in liberal studies and gender and sexuality studies from The New School for Social Research in New York City. Her thesis, supervised by Dr. Gina Luria Walker, traced the historical reception of Diotima in Plato’s Symposium and, more broadly, explored the relationship between learned women and epistemological authority. She is a member of the New Voices in the History of Women in Philosophy Group at the Center for the History of Women Philosophers and Scientists, based at Paderborn University.