Current and Forthcoming Figures in the Feminist Foremothers of South Asia Series

Sant Phulibai Jat (1568-1646)

Compiled by Namrata Chaturvedi

Sant Phulibai Jat is a major historical figure in the Jat community and in the history of devotional literature of north India. The Jat community is an agrarian community that is widespread all over north India as well as other parts of India and the world. The medieval period of India was marked by the spread of devotional poetry from southern to northern India and from the western to eastern India. From the Tamil literature of the 8th century to the Hindi literature of the 18th century, bhakti or devotion was a diverse yet unifying poetic force in India.

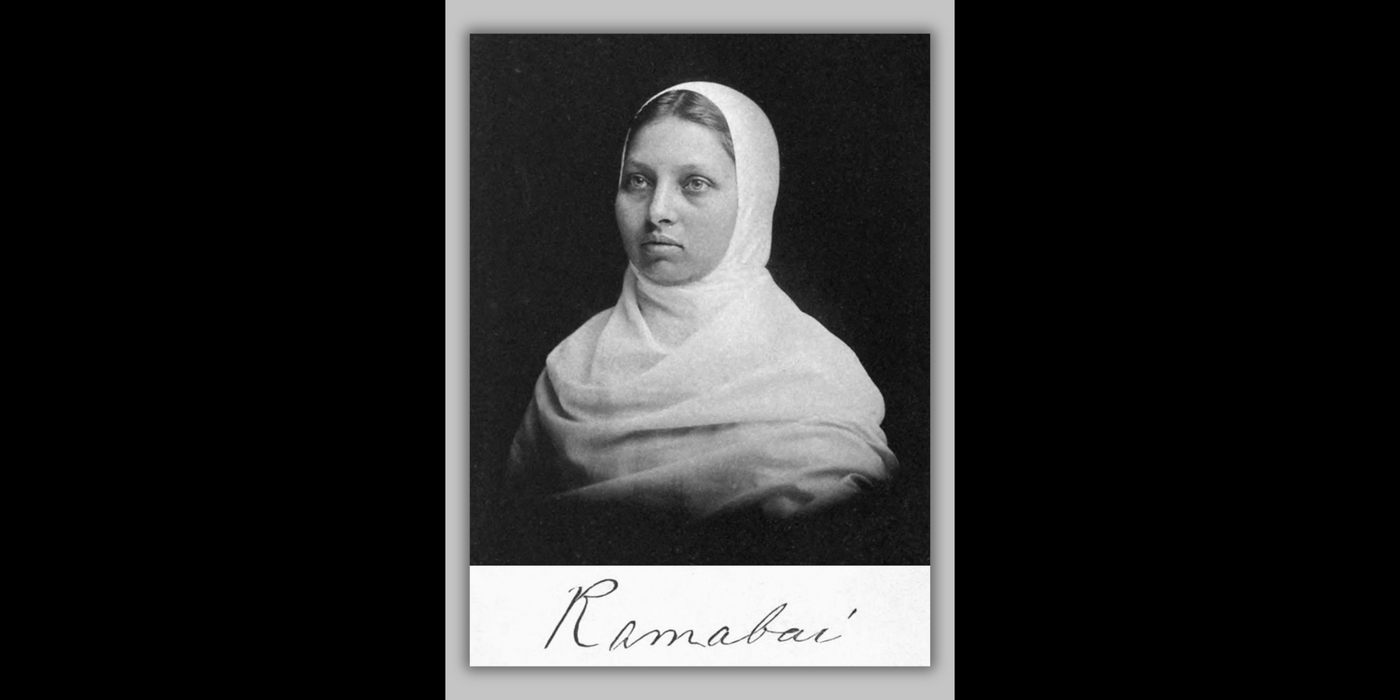

Pandita Ramabai Saraswati (1858-1922)

Compiled by Raj Hansh Ojha and Priyanka Jha

Known as the Feminist Foremother, Ramabai Saraswati’s immense contributions significantly improved the condition of women in the late 19th and early 20th Century, offering a blueprint for the future generations. A social reformer, educationist, and women's rights activist, Pandita Ramabai Saraswati was a pioneer in advocating for an egalitarian and dignified selfhood for women. Her critical engagement with the patriarchal religious and social order of her times, as an erudite scholar of the Shastras and the religious canon, paved a new path for Indian Women. Her work, ‘The High Caste Hindu Women’ (1887), a pioneering feminist text of her times, raised significant questions about the entrenched nature of dual patriarchies of the colonial and native masters and demanded the necessity of education for the girls and women for their dignified selfhood. Her Seva Sadan and Mukti Sadan (Residential schools) were groundbreaking institutions for women’s education.

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (1903-1988)

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, in the truest sense, is one of the shapers and makers of Modern India. As a key leader in the nationalist struggle, she was an Anti-Imperialist, Socialist, and a leader of the Women’s movement. She played a key role in the formations of organizations like All India Women’s Conference, Congress Socialist Party, and was a formidable leader of the Indian National Congress. Her contributions, both well-known and those in want of attention and research, are numerous. For instance, she advocates for reproductive rights and bodily autonomy for women. In the post-Independence, partition-torn country in 1947, she played a key role in the rehabilitation of the refugees, followed by her setting up of the Indian Cooperative Union, which not only helped in providing opportunities for the humane rehabilitation of many men and women but was also significant in creating the town of Faridabad. One of her most crucial interventions was towards the revival and revitalization of the umpteen arts and crafts of India and South Asia, which were on the brink of extinction. As an institution builder, she set up a large number of Akademis and Institutions, dedicated to the ‘cultural life’ of the newly Independent India, which still stands tall and continues to work on the vision and ideas she had for India.

Mahadevi Varma (1907-1987)

Invoked as one of the leading feminist literary voices of modern India from North India, her voluminous contributions brought to light many of the concerns of the time, most significantly the “condition of women.” As one of the pillars of Chhayavaad, the literary renaissance in Hindi writing, Mahadevi was among the foremost women writers who, through her poetry, prose, essays, editorials, and other contributions, articulated the necessity of contesting the binary of the “personal” and the “political,” arguing that this division was artificial and that the “cultural” and the “social” realms must be understood as deeply “political.” Her editorship of Chand, the leading women’s journal of the 1930s–40s, was instrumental in bringing forth writings with deep imprints of nascent feminism. She was also a key participant in the nationalist struggle for independence against British colonialism, with pronounced Gandhian influence.

Sant Dayabai (1728-1798)

Sant Dayabai is remembered in the history of devotional poetry in India as an exemplar of guru bhakti (devotion to one’s guru). Her guru, Sant Charandas Maharaj (1703–1782), taught a simple path to divine realization that rejected unnecessary ritual, caste hierarchies, and false religiosity. Living in Delhi, Charandas composed numerous devotional and yogic texts in sadhukkadi bhasha (vernacular saint language) outlining yogic methods and their benefits. He also authored a Persian text, Muhit-i-Marifat (still untranslated), which delineates stages of God realization through yoga.

The tradition’s gaddis or thambas were widely distributed across North India, eastern India, and into Afghanistan. W. Crooke recorded 161 Charandasis in several districts by the late nineteenth century, while the same census listed 1,253 in Panjab. The Census of 1901 recorded 1,773 Charandasis in the United Provinces, suggesting earlier figures may have been inaccurate. Once a vibrant saint tradition with fifty-two centres, it has now dwindled to only a handful, likely due to the loss of archives, untranslated vernacular literature, and Charandas’s reluctance to expand land holdings.

Haimabati Sen (c. 1866–1933)

Haimabati Sen (c. 1866–1933) was one of India’s earliest women physicians and a pioneering memoirist whose comprehensive account of her own life documented the systematic oppression faced by savarna Hindu widows in colonial Bengal. Born into an affluent kulin (elite) Kayastha family in the Khulna district of former East Bengal, now Bangladesh, she became a child widow at the age of ten, remarried as an adult, and obtained medical training at Campbell Medical School in Calcutta. Sen worked as the Lady Doctor at Hughli Dufferin Women’s Hospital and maintained a private practice while raising five biological children and adopting over four hundred children whose mothers had died in her hospital or been abandoned. Her memoir, written in Bengali in the 1920s and 1930s, provides an unflinching and intimate account of child marriage, customs of widowhood, sexual violence, marital rape, professional challenges, and the complex negotiations of patriarchal oppression by a pioneering professional woman in colonial India.