I have long been drawn to the stories of women whose accomplishments were extraordinary, yet who have been mostly unrecognized by history. For more than 25 years, I have made this my focus as an artist and a historian, working with portraiture, documentary film, and, most recently, a book-length biography of a woman named Elaine Black Yoneda, released in December 2021 by Temple University Press.

My subjects are often Jewish women, often labor activists. Telling their particular life stories offers me the ability to counter universalizing tendencies that tend to flatten individual experience in favor of broad claims, and ones that cannot be attentive to the intersectionality of women’s identities. “The personal is political,” goes the old feminist adage. Representing close-to-the-ground views of women’s lives enables us to see the ways that women negotiated work, career, family, and other commitments while all these elements were in tension with one another.

When I began my doctoral studies as a historian, biography had fallen out of favor, especially with labor and gender historians. I understood this to be a reaction against canon formation—we did not need to add to the list of Great Men and their accomplishments; we needed to challenge the very idea of elevating individual achievement at the expense of telling the history of the masses. And yet, for me, biography continued to hold allure. In biography, I found the ability to avoid “abstract causation and ‘conceptual’ history,” as described by the editors of the recent book The Biographical Turn: Lives in History. Another argument against biography has been that a cohesive thesis cannot be devised from the arbitrary starting point (birth) and end point (death) of a person’s life, let alone the happenstance assemblage of experiences that any individual encounters. But, as a number of “new biographers” and “feminist biographers” have explained, biography allows the historian to be attentive to the messiness of real life, and biographers to reveal the ways that lives may not be lived in full coherence.

Piecing together the lives of unfamous women is not always a straightforward endeavor. The feminist biographer knows that it is a privilege to appear in the archives, a privilege most often not accorded to people of all genders, sexualities, races, abilities, cultures, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Gender historians, as well as those who study other marginalized subjects, learn to look and to read differently—to creatively mine a wide variety of sources including interviews, oral histories, and unpublished materials; and to be attentive to lacunae. Often what is not recorded is as significant as what has been included in an archive, and it can be very illuminating to interrogate why something was left out.

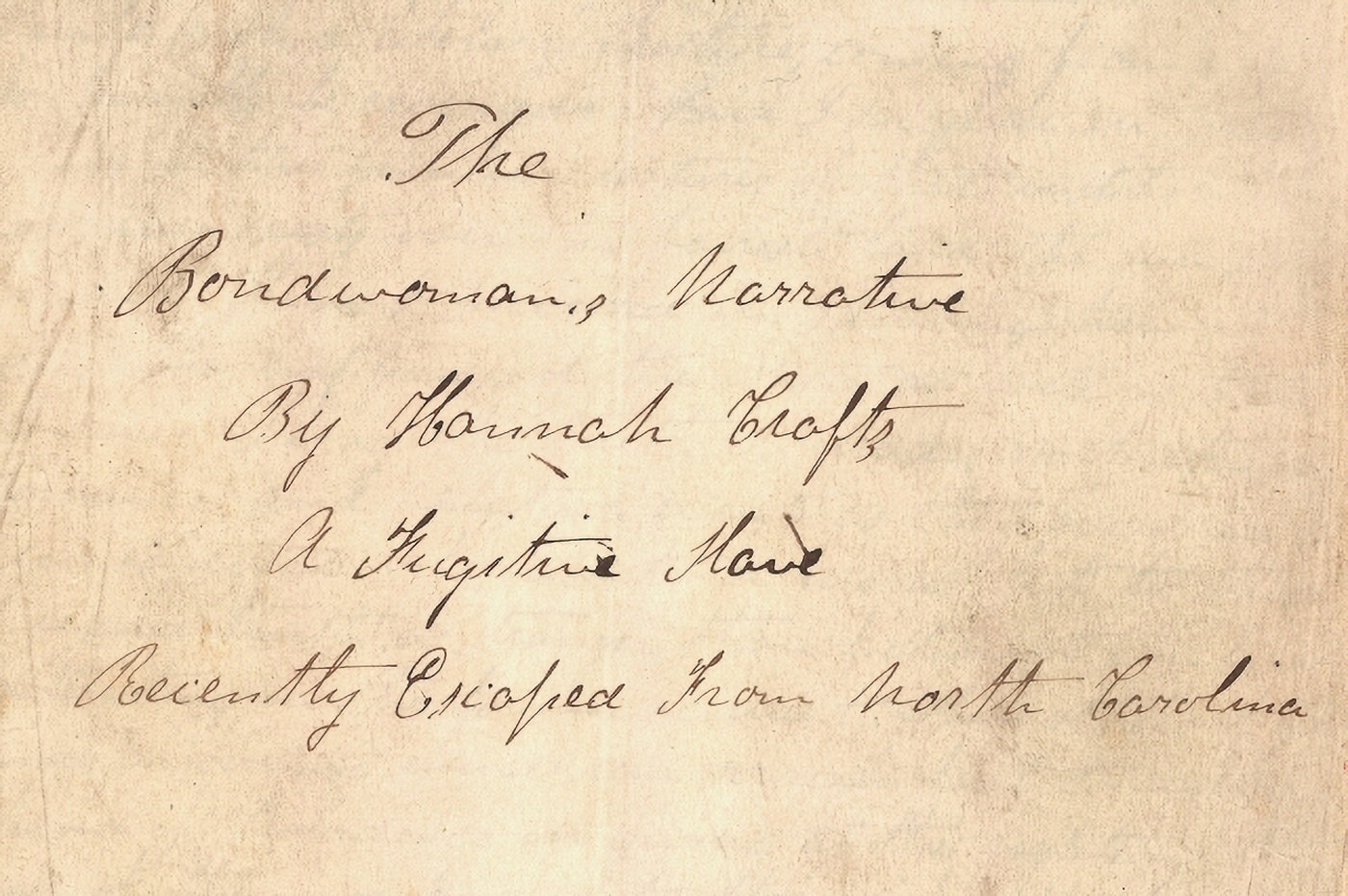

All of this I learned from a few groundbreaking works of feminist biography, including Patricia Cline Cohen’s The Murder of Helen Jewett, Carolyn Steedman’s Landscape for a Good Woman: A Story of Two Lives, and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785–1812, among other works. These biographers drew on laconic and scant information, or personal experience, to reassemble for their readers (respectively) the life of an early-20th-century prostitute, the author’s working-class mother, and an 18th-century midwife. In the case of Ulrich, the precious archival material had long sat in plain view, like Poe’s purloined letter. Martha Ballard’s diary had been collecting dust for years as generations of (male) historians dismissed the laconic accounting of this midwife’s birthing of more than 816 babies as a primary source of little value. In Ulrich’s hands, the diary became a springboard to understand the agency, career, and business acumen of this early-19th-century woman, defying long-held notions of the lives of women during this time period in the United States. A similarly important document that was long neglected—though a novel, not a biography—is The Bondwoman’s Narrative by Hannah Crafts, which sat in an attic until it caught the attentive eye at auction of Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who purchased, authenticated, edited, and subsequently published this extraordinary manuscript written by a woman who liberated herself from slavery in North Carolina in the mid-19th century.

When we valorize, for example, large-scale history painting over fine needlework in cultures where women’s creative production was mostly pursued within domestic space, we are already creating the conditions under which women’s work in certain times and places could not achieve the same levels of visibility as that of men, both within their lifetimes and in the historical record.

When we extend this analysis to hierarchies between “fine arts” versus “crafts” across geographies and cultural contexts, the biases inherent in the traditional art historical frameworks become even more stark.

Feminist biography is, then, a methodology as much or more than it is a matter of subject. Second-wave feminists did important work in reclaiming women who had been lost to history. Third-wave scholars proposed new ways of thinking about how gender is a lens through which we can analyze society, culture, and the lives of all people, and in ways that intersect with race, class, ability, geography, and other vectors of difference. Historians must pay close attention to the questions we ask about the opportunities as well as the constraints faced by our subjects, the categories of analysis by which we assess their achievements, what we consider to be valuable source material, and whose stories we believe are worth telling. With this level of attention, we can claim the value of telling the life stories of marginalized individuals in order to illuminate the ways in which they challenged dominant discourses, occupied roles of their own self-fashioning, and managed all such efforts within their own specific times and places.

Rachel Schreiber, M.F.A., Ph.D., is an historian, artist, and designer, and the executive dean of Parsons School of Design.