In 1975, as the women's movement inched its way into the masculine halls of literary study, the Cambridge scholar Juliet Dusinberre suggested that Shakespeare’s drama “deserves the name feminist." In his plays, she wrote, “the struggle for women is to be human in a world which declares them only female.” The Oxford scholar Anne Barton similarly observed that “Shakespeare’s sympathy with and almost uncanny understanding of women characters is one of the distinguishing features of his comedy, as opposed to that of most of his contemporaries.” In fact, she went on, Shakespeare’s heroines “not only tend to overshadow their male counterparts, as Rosalind overshadows Orlando [in As You Like It], Julia Proteus [in The Two Gentlemen of Verona], or Viola Orsino [in Twelfth Night]: they adumbrate and urge throughout the play values which, with their help, will triumph in the more enlightened society of the end.” In other words, when the ending is happy, resulting in a more humane, understanding world, it is often because the heroines win.

At the time, these observations provoked fierce controversy. The dusty Shakespeare establishment—almost entirely male—was not pleased to have English literature’s supreme genius co-opted by female scholars and declared a feminist.

“I—and others—shed blood,” Dusinberre reflected years later, looking back on the battle. “Shakespeare then, as now, had the status of the Bible in British culture. No one, and especially no woman…must make free with the sacred text.” The rankled scholars were, she noted, “still immersed in preconceptions which Shakespeare discarded about the nature of women.” Dusinberre wondered in retrospect what the battle was really about.

“In the simplest terms, it was about the asking of questions. The educated world, with its cherished traditions of free speech, operates its own censors,” she wrote. “Scholars can hide even from themselves their own inner censorship, a process familiar to all students of literature in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. What can and cannot be said.” Fifty years later, feminist readings have gone mainstream in Shakespeare studies as they have in literary studies generally. It is now unremarkable for scholars to reflect on the moral authority of Shakespeare’s heroines or the many ways in which they outwit his male characters. Like the heroines they studied, Dusinberre and her feminist comrades triumphed. But the censors—“sometimes overt…but more often closely concealed,” Dusinberre observed—still operate in Shakespeare scholarship. Asking questions remains intellectually dangerous.

For example, how did Shakespeare come to write feminist drama? Women’s struggle to be human is not, historically, a subject of much interest for men. What accounts for his “uncanny understanding” of women—an understanding apparently lacking in his fellow playwrights? And why, though Shakespeare wrote highly intelligent, even erudite women, did he neglect his own daughters’ education? The women of the plays write letters, compose sonnets, and read Ovid. “It is striking how many of Shakespeare’s women are shown reading,” the Harvard scholar Stephen Greenblatt has remarked. It is striking because Shakespeare’s daughters were, by all appearances, illiterate. The most dangerous question of all—the most censored and ridiculed—remains: Did Shakespeare actually write the body of works we call Shakespeare?

The idea of a female Shakespeare is easily dismissed as a kind of modern feminist fantasy—a desire to replace the father of English literature with a mother.

But the feeling of something distinctly female about Shakespeare is old. In 1599, the poet John Weever wrote of Shakespeare’s ‘issue,’ suggesting his works were born not only of Apollo but also of “some heaven-born goddesse”:

Honie-tong’d Shakespeare when I saw thine issue,

I swore Apollo got them and none other,

Their rosie-tainted features clothed in tissue,

Some heaven-born goddesse said to be their mother.

Weever wrote, said to be their mother, as though it were a rumor, a half-heard whisper at court. Did the works have a mother as well as a father? In 1664, the poet-philosopher Margaret Cavendish marveled at Shakespeare’s ability to dissolve into his characters; “One would think he has been Metamorphosed from a Man to a Woman,” she wrote, “for who could describe Cleopatra better than he hath done, and many other Females of his own Creating.” Virginia Woolf also thought Shakespeare had an androgynous mind—a “man-womanly mind,” she called it. The Victorian critic John Ruskin remarked on the virtue of Shakespeare’s female characters, compared with the tragic flaws and foibles of his men, and concluded: “Shakespeare has no heroes—he has only heroines.” Orson Welles, who acted in and directed numerous Shakespeare productions, observed that “Shakespeare was clearly tremendously feminine.”

“Was it possible that women were involved in Shakespeare?” I posed the question to Carol Symes, a Harvard-educated, Shakespeare-doubting historian at the University of Illinois.

“Oh, yeah,” said Symes. “This is one of those things that’s probably always going to be unprovable precisely because of the undocumented nature of women’s work.” Symes’s scholarship as a historian of the theater has suggested that the plays were likely a collaborative effort, not only because early modern playwrights tended to work collaboratively but also because of the “extraordinary variety of expert knowledge and expert epistemologies” exhibited in Shakespeare’s work. Though the group was probably led by “somebody with extraordinary vision,” she thought it was impractical to compress all that knowledge into one person. The involvement of a woman—or women—would “make a ton of sense,” she added. “The seemingly embodied understanding of women’s positionality and plight just shines through those plays amazingly.”

If history gets distorted by tradition, it also gets distorted by assumptions that documented history is the whole history–that recorded truth is the complete truth.

Since only men’s names are included on lists of known commercial playwrights, and only men and boys joined playing companies, the Elizabethan theater was long assumed to be an exclusively male realm. But more recent scholarship has shown that women were actively involved in theater. Aristocratic women acted as patrons of playing companies. Women from the middle classes supported the day-to-day business, creating costumes and stage props, collecting entrance fees, and lending money for productions. Some women performed as actors in local festivals, private productions, and courtly masques. At least one woman—Mary Frith, alias Moll Cutpurse, a smoking, cross-dressing pickpocket from the London underworld—delivered a notorious performance at the Fortune Theatre in 1611.

Though women were not identified as commercial playwrights, that does not mean they were not writing. They wrote liturgical drama and royal entertainments. They produced translations. For example, Jane Lumley—a young noblewoman and the first person to translate a Greek play into English—translated Euripides’s Iphigenia, listing speakers as she did so, suggesting the play was intended for private performance. In 1560 a Protestant woman named Anne Locke became the first person in England to publish a full sonnet sequence, “A Meditation on a Penitent Sinner,” but prefaced the sonnets with a letter claiming they weren’t hers; they were “delivered me by my friend with whom I knew I might be so bolde to use and publishe it as pleased me.” A classic excuse! For years, scholars assumed the “friend” was a male writer. The sonnets weren’t ascribed to Locke until 1989, when scholars compiled evidence of textual parallels between the sonnets and her letter.

Locke’s disavowal of her authorship can be seen as an instance of the modesty topos. Anonymity for women was a “relic of the sense of chastity,” observed Virginia Woolf. They “did homage to the convention, which if not implanted by the other sex was liberally encouraged by them…that publicity in women is detestable.” Appearing in print as a woman carried a moral stigma. The poet Richard Lovelace wrote, for example, of a woman who “Powders a Sonnet as she does her hair, / Then prostitutes them both to publick Aire.” To publish as a woman—to sell one’s words in the marketplace—was immodest, a kind of prostitution. Hence their use of pseudonyms such as “Constantia Munda” (Latin for “pure constancy”) or “Jane Anger,” who identified herself only as a “gentlewoman at London,” concealing her identity even as she lashed out against misogynist depictions of women. “It was ANGER that did write this,” she explained in Her Protection of Women, pointing out that men misrepresent women because “they think we will not write to reprove their lying lips.” Her polemical pamphlet was published in 1589, on the eve of the decade that saw the explosion of Shakespeare’s plays, radically rewriting the representation of women.

In 1593 the critic Gabriel Harvey referred cryptically to an “excellent gentlewoman” who was writing “strange inventions and rare devices.” Her style is “the tinsel of the daintiest Muses and sweetest graces, but I dare not particularise her Description…without her license or permission,” he wrote. Still, he couldn’t help heaping praise on her. “She is neither the noblest, nor the fairest, nor the finest, nor the richest lady, but the gentlest, and wittiest, and bravest, and invinciblest gentlewoman that I know.” Of her writing, he noted that “all her conceits are illuminate with the light of Reason; all her speeches beautified with the grace of Affability…In her mind there appeareth a heavenly Logic; in her tongue & pen a divine Rhetoric. I dare undertake with warrant, whatsoever she writeth must needs remain an immortal work, and will leave, in the activist world, an eternal memory of the silliest vermin that she should vouchsafe to grace with her beautiful and allective style, as ingenious as elegant.”

Who was the excellent gentlewoman writing “immortal work” in 1593, the very year Shakespeare’s name first appeared in print? Some scholars have suggested that she was just a fiction created by Harvey. Others have wondered if she was Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke and sister of the poet Philip Sidney. According to Harvey, the gentlewoman had written sonnets as well as a comedy. Were women writing plays?

When Mary Sidney published The Tragedy of Antonie (1592), her translation of a French play, she became the first woman to publish a play in English. She revised and completed her brother’s English versification of the Psalms, displaying, in the words of one scholar, a “technical virtuosity in inventing verse forms [that] can scarcely be exaggerated.” (At his death, Philip had translated only 43 of 150.) At the same time, she turned Wilton House into a literary salon—what one scholar has called “a workshop for poetical experimentation, the seedbed of a literary revolution”—gathering writers around her, supporting them, and assigning them works to write. “She enjoys the wise Minerva’s wit and sets to school our poets everywhere,” wrote the poet Thomas Churchyard. The poet Samuel Daniel credited her with having taught him, calling Wilton “my best school.” What else did she do? “The complete body of her works eludes us,” writes the scholar Margaret Hannay, noting that “much of what she wrote and translated has disappeared.” One reason may have been “some reluctance to put her original works into print, despite her boldness in printing her translations under her own name.”

In France, Marguerite de Navarre was writing comedies performed for the court. In Italy, women were writing plays and acting in them—and a few Italian troupes traveled across the channel to play for the Queen of England. What did Englishwomen make of the European example? If French and Italian women were writing plays, it is hard to believe that Englishwomen were not. By 1613, Elizabeth Cary had become the first Englishwoman to publish an original play, The Tragedy of Mariam, though even then she was discreet: the title page identified her only as “that learned, virtuous, and truly noble Ladie, E.C.” The play was not performed on a public stage, but scholars argue that it could have been staged at a private residence.

The ideological constraints in which women operated are more likely to have prevented acknowledgment of a woman’s authorship than to have actually prevented them from writing plays, argues the scholar Phyllis Rackin.

In other words, the constraints “make it more, rather than less, likely that some of the many plays whose authorship is anonymous were actually written by women and also that women collaborated in writing plays whose authorship was attributed only to men.” Renaissance households were not simply domiciles but places of production in which every resident had a part, she notes: “The household of a baker produced bread; the household of a glover produced gloves. The household of a playwright is likely to have been organized on similar principles.” The theatrical business, like other businesses, was “often a family affair.” Plays could have been “the product of his wife’s or daughter’s work as well as—or instead of—his own.

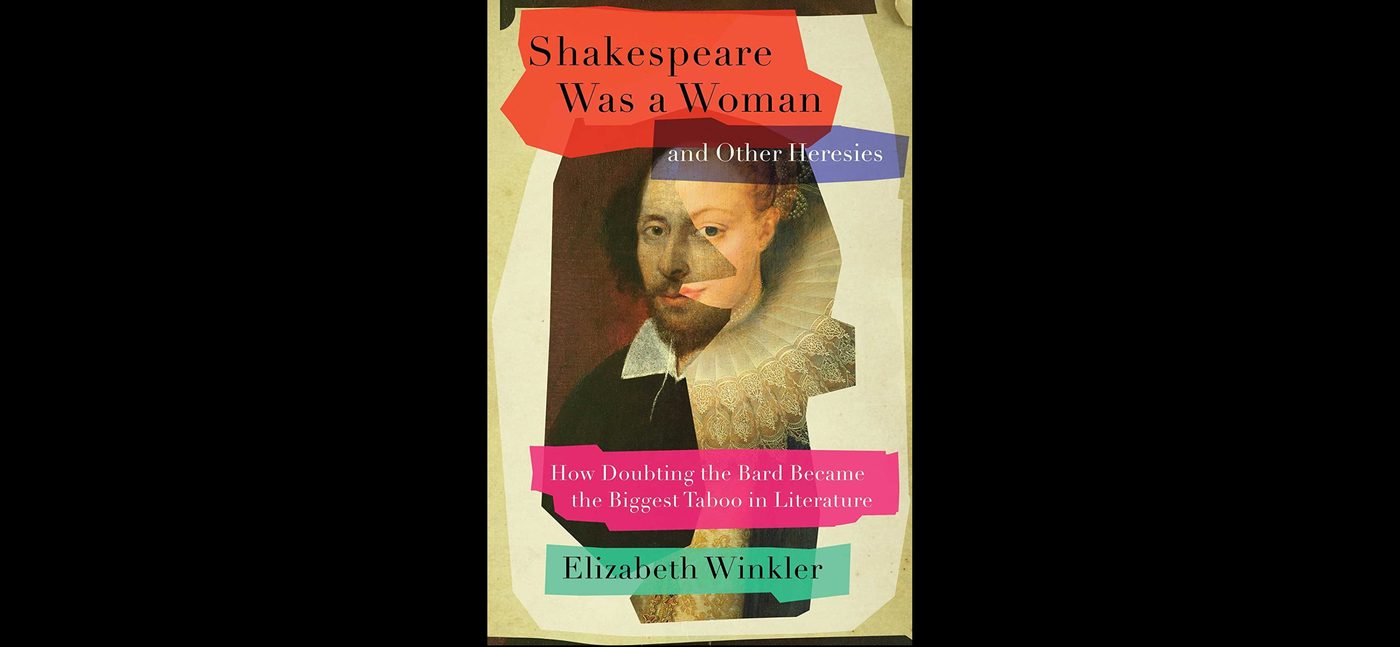

Elizabeth Winkler is a journalist and book critic based in Washington, DC. Her articles and reviews have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The New Republic, The Economist, The Times Literary Supplement, and The New Yorker, among other publications. She received her undergraduate degree from Princeton University and her master's in English literature from Stanford University. Her essay in The Atlantic, "Was Shakespeare A Woman?" was selected for The Best American Essays 2020.