In 1655, a 17-year-old girl began her diary; “I, Elisabetta Sirani, was born on Friday the 8th of January 1638.” The list of about 200 artworks that follows is, to this day, the only known autobiographical ledger by a woman artist of the 16th and 17th centuries. It tells of secret meanings hidden in subject matter; of visits from princes, princesses, dukes and duchesses; of diamond-encrusted crosses; of an artist with incredible originality, autonomy and wit. Sirani would become one of the most widely collected artists in her home city of Bologna, paving the way for generations of women artists after her. Yet what her diary conceals is the ingenuity with which she navigated the societal obstacles she faced along the way. To understand this, we must turn to her works themselves.

Despite the support of several well-connected family friends and the success of her Bolognese predecessor, Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614), Sirani faced an uphill battle to gain recognition for her talent. While her father—the successful artist Giovanni Andrea Sirani (1610-1670)—enabled her creative education, his association with his daughter led critics to undermine Sirani’s individual accomplishments. According to her biographer, patron and good friend Carlo Cesare Malvasia (1616-1693), she intentionally “tried… to detach herself from the ways of her father, putting more effort into her figures so as not to conform to his manner, as Lavinia [Fontana] did to that of Prospero [Fontana (1512–1597)].” Despite this, one of her agents felt the need to reassure a client that “there is no reason at all to suspect that [Giovanni Andrea] has helped his daughter,” due to his disability. Malvasia even brought groups of visitors to watch Sirani paint a work from start to finish, hoping to “bring confusion to those jealous and malicious persons who went about disseminating the story that she was assisted by her father.”

Eventually, Sirani took the matter into her own hands, and began signing her works. While an artist’s signature is a familiar sight today, the practice only began to take off in the 15th century. By the 17th century, male artists were signing about a quarter of their total production, and Bolognese male artists even less (about 10%). Sirani, however, signed an unprecedented 70% of her paintings. She always used either her full name or the gendered proper noun “La Sirana,” reducing the likelihood that her works would be mistaken for her father’s. She also refused to include any reference to her marital status in her signature, whereas “virgin” or “daughter” were sometimes affixed to the signatures of Lavinia Fontana and Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625). Even Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653) added her father’s name—Lomi—into her works where it would benefit her reputation among Florentines. Sirani’s staunch approach reflects her status as a “lifelong singlewoman,” someone who made the radical choice (at the time) never to marry and to focus on her career. It is probable that she tactfully avoided references to men in her signatures as a means of testifying to her autonomy as an artist.

Over time, Sirani began weaving her signature into the very composition of her paintings. Her favourite method was to work her name into the garments or soft furnishings in her paintings, as embroidery or buttons. By 1664, she had mastered this approach. In Delilah (1664), the individual letters of Sirani’s name are entwined with the golden acanthus leaves adorning Delilah’s sleeves (fig. 1). Other embroidered examples from this year are found on the trim of the cushion upon which Galatea (1664, Modena, Museo Civico d’Arte) sits, and on the velvet backing of the chair upon which Portia (1664, Fondazione della Cassa di Risparmio) rests her foot. In Allegory of Justice, Charity and Prudence (1664), a spark of inspiration even sees her place each letter of her name into a different button on the front of Justice’s dress (fig. 2). These integrated signatures prove Sirani’s involvement in designing the composition of her paintings. They also double as a jibe at her doubters: since embroidery was regarded as ‘women’s work,’ Sirani may have realised that metaphorically ‘stitching’ her name into her paintings could recast them as ‘women’s work’ too. This was only reinforced when her paintings were chosen to be reproduced in embroidery by the orphaned girls of the Conservatorio delle Putte di Santa Marta, the oldest female education institute in Bologna.

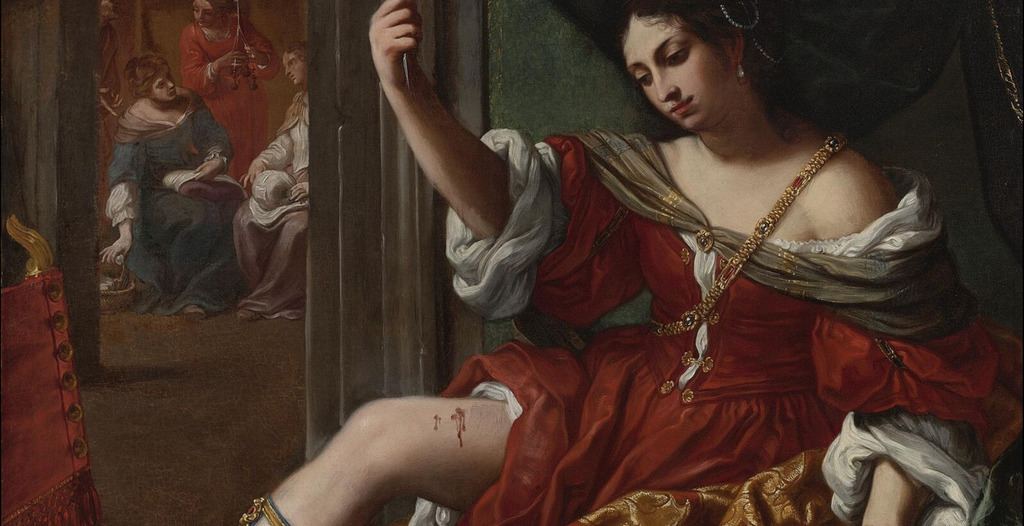

In other instances, Sirani’s signature embellishes key elements of the composition. In Venus Chastising Cupid (fig. 3), her name adorns Cupid’s quiver. The quiver holds the arrows which cause people to become infatuated with one another, just as Sirani possesses the power to captivate viewers with the beauty of her paintings. In her theatrical Judith (fig. 4)—thought to be a self-portrait—Sirani’s name is etched into the wooden stage which supports and elevates the Biblical heroine, implying her role in showcasing her own achievements and those of historical women. These interpretations are justified by her own admittance to making symbolic choices throughout her diary, which grew bolder over the course of her career. When the Duchess of Brunswick visited Sirani’s studio in 1665, shortly before the artist’s unexpected death, she slyly painted an allegory of Self-Love in front of her: a Cupid admiring himself in a mirror and about to wound himself with his arrow. Our only explanation of this is “understand me those who can, for I understand myself.”

By forging a name for herself and asserting her skill, Sirani carved out space in the male-dominated Bolognese canon for women artists. Her clever manipulation of the traditional signature transformed it from an act of self-promotion into a tool for social change, an integrated sign of authorship proving that women were highly capable artists. She monetised the scepticism of her critics by encouraging them to look closely and to see her works as curiosities. Sirani exemplifies how small changes which gently challenge engrained assumptions can have a significant positive impact on the long-term flourishing of women in society.

Anna Pratley is an MA graduate of the Warburg Institute, where she studied Art History, Curatorship and Renaissance Culture. She researches women artists of the 17th century, specialising in women limners operating in post-Restoration England and what feminist surveillance theory may tell us about their work. She is also a member of the Women’s Studies Group 1558-1837, and has previously written a blog post for ArtHerstory on the 17th century miniaturist Susannah Penelope Rosse.

Learn more from the Elisabetta Sirani Schema.