With its mission of feminist historical recovery, The New Historia is the ideal place to present news about the Venetian Humanist, philosopher, and orator Cassandra Fedele (Fidelis), ca. 1465 – 1558. Misconceptions about her life that have been accepted and uncritically repeated over the centuries continue to influence how contemporary scholars think about and discuss her work. Thanks to the evidence I have discovered, I am now able to correct errors, point out intentional misdirection embedded in the source narratives of Cassandra’s life, and add abundant new information.

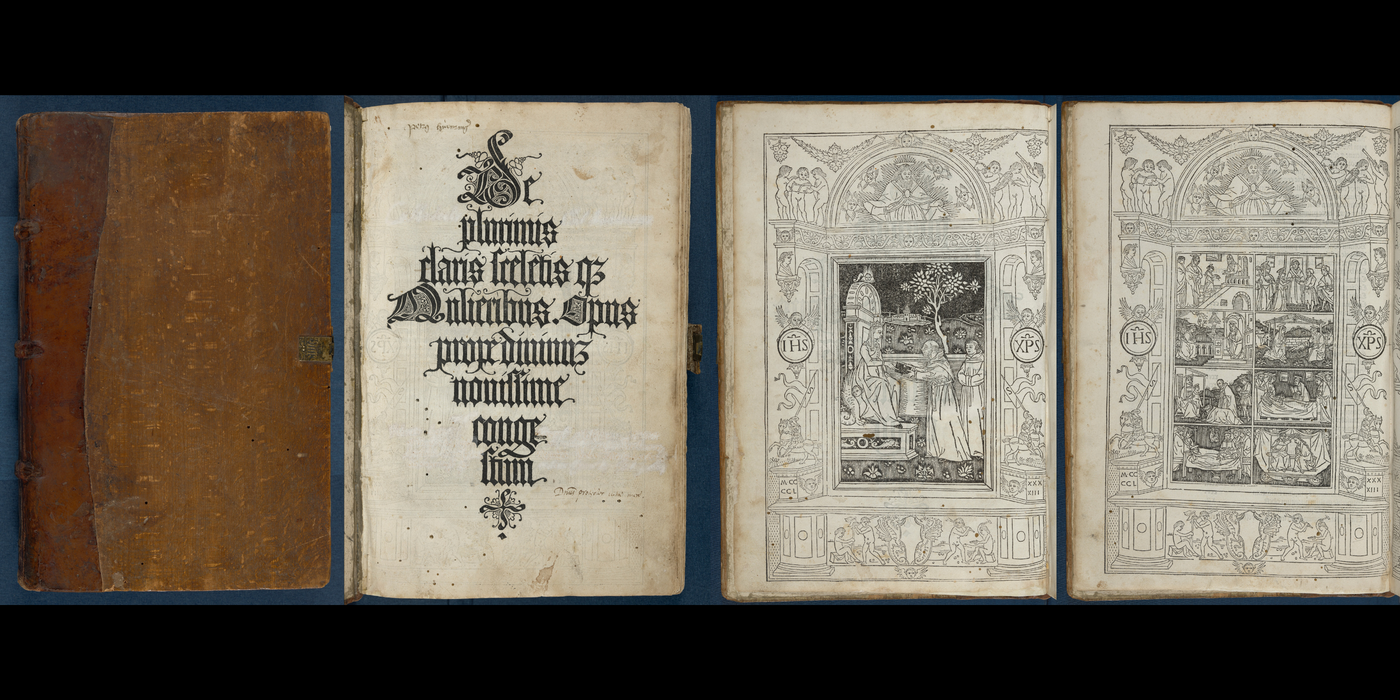

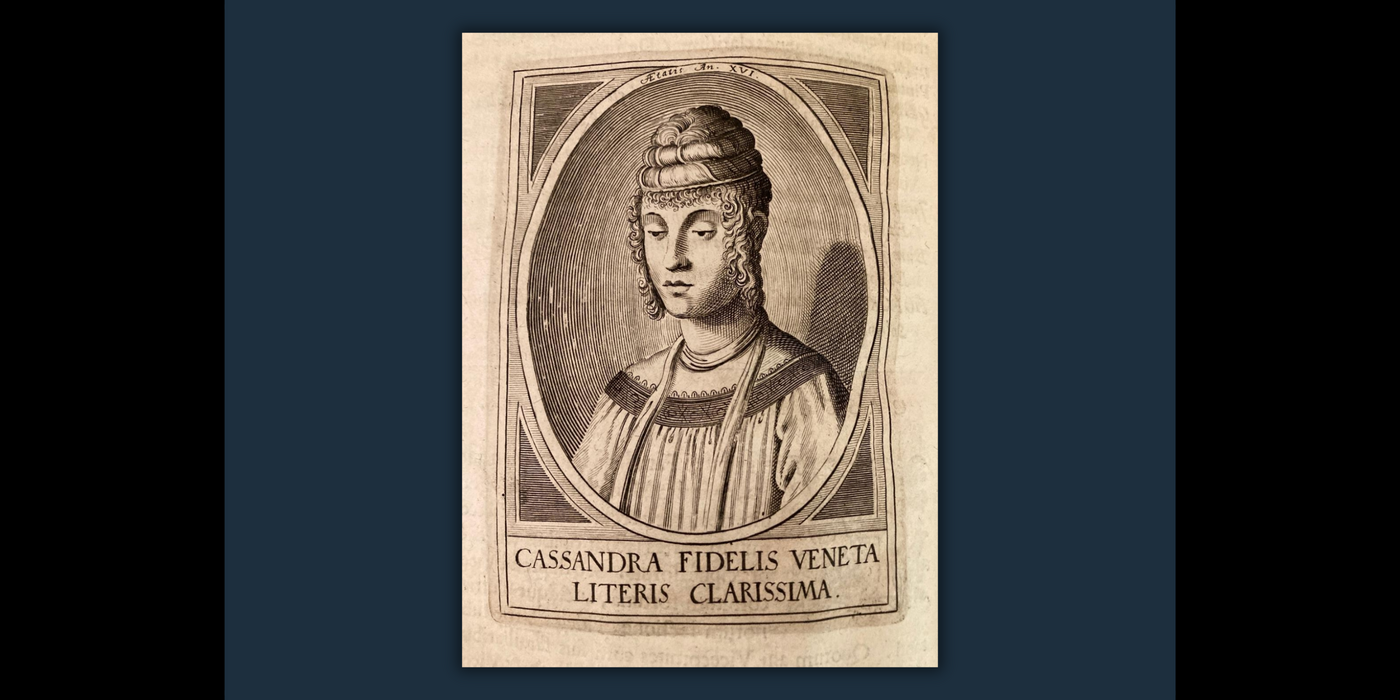

I became interested in Cassandra in 2012 when I was writing about the Augustinian monk and author, Giacomo Filippo Foresti of Bergamo’s entries about the Bellini family in his Supplementum chronicarum (1483) and later editions. Studying Foresti, I learned about his biographical encyclopedia of famous women, De plurimis claris selectisque mulieribus, Ferrara, 1497. Foresti met Fedele in Venice around 1487. In De Cassandra fideli veneta virgine oratrice e ph(ilosoph)a), he wrote the astonishing statement that he had Cassandra’s portrait drawn and cut for the woodblock portrait that illustrates this entry. I also learned about a portrait of Cassandra (ca. 1481) that she wrote was painted by “Bellini.” Now lost, the painting is only known from the engraved reproduction in Giacomo Filippo Tomasini’s Vita of Cassandra, 1636. This engraving of the 16-year-old Cassandra (and its derivatives) depicted her with the pettinatura a fungo hairstyle. It is the most widely known image of her today. I set myself the challenge of finding the missing Bellini portrait.

I began to read Cassandra’s letters and orations. First collected, edited, and published by Giacomo Filippo Tomasini in Latin (1636); her writings have now been translated into English, Italian, Castilian Spanish, and Catalan. I delved into secondary literature on her life from the sixteenth to twenty first centuries, including Tomasini's Vita ( 1636 and 1644), Maria Pettretini’s morally uplifting biography (1814), and Cesira Cavazzana’s magisterial article presenting the first serious archival research on Cassandra (1906). I read illuminating and provocative essays by 20th and 21st-century scholars in the fields of biography, gender studies, Classical languages, Venetian and Paduan Humanism, rhetoric, book culture, Spanish history, and art history.

Surveying the literature, I came to realize that Fedele studies suffer from an almost complete lack of original primary sources and documents. How was it possible that there could be virtually no archival trace of her prominent citizen family? Not one of the original manuscripts of her writings have been found.

We only knew Cassandra’s “voice” through her three published Latin orations—with their Ciceronian oratorical structure, stylizations and conventions—and through 123 letters filled with courtesies, obeisance, self-effacement, as well as occasional flashes of affection and humor. Apart from dictated tax declarations and her 1556 will (probated), we had virtually nothing from her in volgare.

For her life story and genealogy, we had only Tomasini’s Vita. Although Cassandra alluded to various relatives in at least twenty-five of her published letters, she never named her parents. Foresti named Angelo Fedele as her father and Tomasini, citing Cassandra’s grand-nephew Paolo Leone, wrote that her mother was said to be Barbara from the Venetian Leone family, at whose bosom she learned and practiced girls’ work. Tomasini speculated that her mother must have died early and was not present in Cassandra’s life.

Vexingly, since Tomasini’s time, writers have recycled—as certainty—Tomasini’s tentative statement that Barbara Leone was Cassandra’s mother. The shadowy figure of Barbara and her negligible influence on her daughter persists to this day, shaping the way Fedele is thought about and presented. In analyzing Cassandra’s rhetoric, scholars including Margaret L. King, Virginia Cox, Diana Robin, and Sarah G. Ross have convincingly argued that Cassandra’s intentional rhetorical strategies of self-effacement, minimization, and her use of the father-daughter paradigm rendered safe her interactions with her male correspondents and guests. Be his influence positive or negative, the father’s influence always seems to predominate.

Little has been added to the documentary record since Cavazzana published Cassandra's husband Gianmaria Mapello’s 1515 will and Cassandra’s 1556 will, which was dictated to the notary Beneto Baldigara. With evident frustration, Cavazzana wrote that Barbara Leone seemed to be an archival dead end.

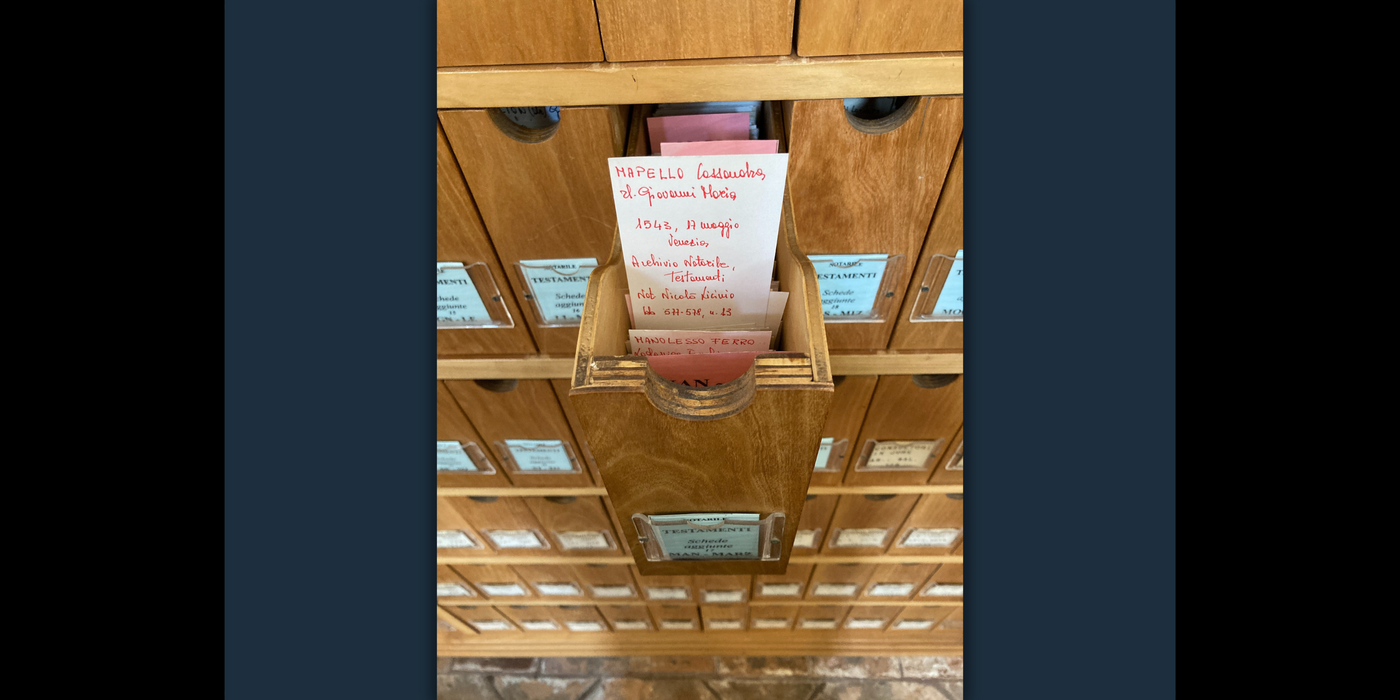

In 2013, while browsing through a supplemental drawer of file cards of wills at the Archivio di Stato di Venezia, I came across a card for the sealed will of Cassandra Mapello, rl. Giovanni Maria, May 17, 1543, Nicolo Licinio, notary. It was Cassandra Fedele, using her married name! Apparently, no one had ever realized its significance. Because it was not her last will, it had remained sealed with red wax. Once the Archivist granted permission for the document to be opened, I held in my hand the unprobated will Cassandra had written in her lovely cancelleresca corsiva handwriting and mostly in volgare. It was a moving, wondrous moment.

Engaged in other projects, it took some time for me to transcribe and translate the will (thank you, Hannah Marcus and Deborah Walberg!). But finally, I was able to read Cassandra in her own Venetian voice. I realized that her 1543 will was completely different from her (published) probated will of 1556. After writing the formulaic phrases naming her executors, funeral, burial, settling of debts, and making bequests, Cassandra declared her intentions. She stated her affection for named relatives, friends, and servants. She expressed irritation towards her husband’s nephews, “no laso niente” (I leave nothing). She arranged for one of her own nephews and a niece to inherit a painting of the Madonna that had belonged to her father. She mentioned the pizzochere (tertiaries), the church of San Francesco de la Vigna, and twice she named “Spiritus Sanctus.”

I realized that this was a clue pointing to the suppressed monastery of Spirito Santo di Venezia, a convent that, to my knowledge, had never been connected with Cassandra. Her only known monastic association was with the Ospedale de le donzelle of the monastery of San Domenico di Castello.

After the pandemic when the Archivio di Stato di Venezia reopened, I began to explore documents of Spirito Santo. In September 2021, I discovered plump folders of papers and boxes of pergamene connected with the monastery’s lawsuit against Fedele and Leone families for control of the real estate and income of Bianca Trevisan de la Seda. Among the hundreds of pages of documents were family tree diagrams of the Fedele, Trevisan de la Seda, Lamberto, and Lion (Leone) families. There were also family members' wills, inventories, financial instruments, real estate purchases and sales, tax declarations, claims of poverty, transcripts of hearings. Most strikingly, there was a posthumous accusation by the abbess of Spirito Santo against Cassandra for fraud and collusion that led to a lawsuit that lasted from her death in 1558 to 1696, and which had generated all these documents.

Since 2021, I have been working my way through the Spirito Santo documents, unraveling the web of intermarried families; learning about the families' assets and income; reading trial transcripts; and following clues. These in turn led to notarial files, tax declarations, and the records of other monasteries. I now have a very clear understanding of Cassandra’s ancestry, including her immediate and collateral relatives, their properties and financial situation, and the issues contested in the lawsuits.

Discovering clear evidence about the strong women in her family, I have come to see that not only was Cassandra “her father’s daughter,” she was her mother’s daughter, and very much her aunt Bianca's niece, too. I have set up a private family tree on a genealogical website to help me manage information about approximately 100 of Cassandra’s relatives. I have compiled Cassandra's schema for The New HIstoria.

I am writing a book presenting the evidence I have discovered, and I link all of this to her writings and images. There is so much left to discover.

The book on the Order of the Sciences, which Cassandra was writing, according to Foresti’s 1497 report, has disappeared—or perhaps she never wrote it. The letters that Tomasini published were the only ones saved and passed down in one branch of the Fedele family, so they give only a partial view of her correspondence. Spanish archives may hold more of her correspondence with Queen Isabella of Castile from the 1480s and '90s than has been discovered to date. From 1514 on, we have little evidence of Cassandra’s Humanist studies and writing. We know nothing about her life in Candia (1515-1520). I still have not discovered the whereabouts of the missing Bellini portrait.

My research on Cassandra Fedele is more than just an exercise in reconstructing a Venetian citizen’s genealogy. By identifying Chiara Trevisan de la Seda as her mother and arguing against her presumed absence, clarifying the complicated family tree, and contesting Cassandra’s own protests of poverty and misery in old age, my discoveries add context, precision, and humanity to our understanding of her life and works. Recently, I have come to know several young scholars who are engaging afresh with her writings and visual images. Together, we are starting to recover Cassandra Fedele.

Amy Namowitz Worthen is Curator of Prints and Drawings, Emerita, at the Des Moines Art Center (Iowa, USA). Her research focuses on illustrated books printed in Quattrocento Venice; on Cassandra Fedele and her family; and on the history of burin engraving. Her recent publications include studies on the training of burin engravers in the 17th and 18th centuries; on Fra Gasparino Borro da Venezia; on the reception of Cassandra Fedele in 17th century Padua; and on Giacomo Filippo Foresti’s Supplementum chronicarum and its entries on the Bellini family. Worthen lives in Venice where she is active as an independent scholar, engraver, and printer.