On September 16th, 2022, a 22-year-old Iranian-Kurdish woman named Mahsa Amini, also known as Jina Amini, was killed by the Iranian “morality” police. She was arrested by this Guidance Patrol for allegedly wearing her head covering improperly. Mahsa’s tragic death sparked outrage and widespread protests in Iran and abroad.

In the beginning, the protests were led by women and conceptualized as a Gen Z movement, but the unrest spread and men and minorities across the country began to support the action. Touted as a feminist revolution, the movement continues, and many speculate it could culminate in regime change for the Islamic Republic of Iran. But why is this happening now? And how much do we really know about the women of Iran? To understand this, we must look at Iran’s revolutionary history.

The women of Iran have long been at the forefront of social justice movements.

They played a central role in the constitutional revolution (1905-1911), which led to the establishment of a parliament and paved the way for the fundamental changes in Iran. They were also integral to the uprisings of the late 70s, which culminated in the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the ousting of the Pahlavi Regime (1925-1979). The revolution was supported by the vast majority of the Iranian public, irrespective of gender, economic standing, and political and religious beliefs. By 1981, the religious elite were able to seize full power, creating a theocracy. It is one of the few full theocracies—alongside the Vatican, Afghanistan, and Saudi Arabia—in existence today.

During the revolution, the Islamic religion was used by intellectuals and the Ulama, guardians and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam, as an ideology for freedom from Western imperialism. Not everyone expected the revolution to culminate in an Islamic Republic. When the mandatory hijab, a head covering worn by some Muslim women while in public, was proposed by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the religious leader of the revolution, there were widespread protests and opposition by women. Even the most pious of Muslims, especially women, did not support the imposition of mandatory Islamic dress. Only extremely patriarchal and Islamic societies, such as Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, enforce this conservative ruling. In Iran, it went against decades of modernization efforts and the cultural sensibilities of most Iranians.

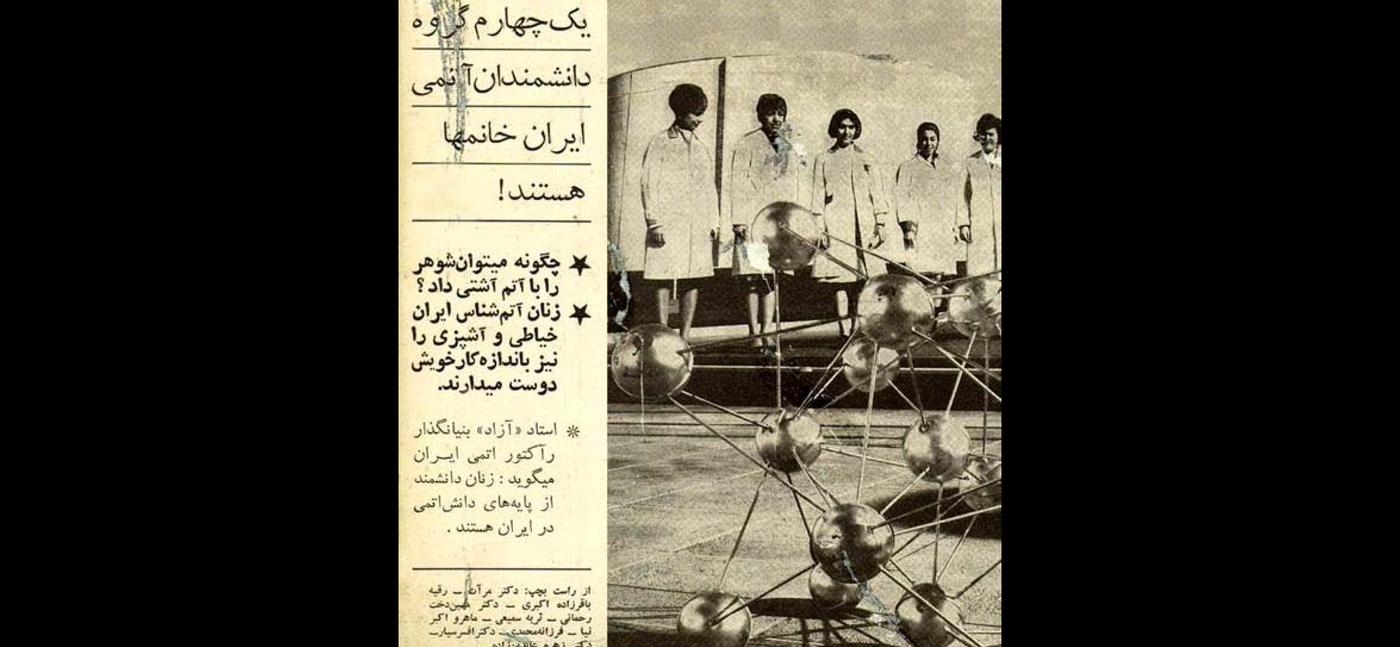

Beyond the 1979 revolution, Iranian women have played pivotal roles in the region as far back as the first Persian Empire, the Achaemenid Empire in 550 BCE; they have been generals, influential queens, diplomats, and community leaders. Iran has a history and culture of women supporting the family, the community, and political life. Sixty percent of university graduates are women, with many working as lawyers, scientists, doctors, engineers, architects, civil servants, and elected politicians. But, over the last four decades, and through various rounds of failed reform movements, we have seen the Islamic Republic chip away at women’s rights and tighten its grip on how women behave in public.

The regime has introduced laws mandating hijab use, lowering the legal age of marriage, allowing for unequal inheritance between daughters and sons, and permitting men to have multiple wives; they have also enforced gender segregation in public spaces and educational institutions and limited access to contraception and family planning services.

As a result, the status of women’s rights has declined in Iran, gender-based violence has increased, and femicide committed by the regime has risen.

While Iranian, we are positioned differently. The first author is Iranian-born, raised in New Zealand, and now residing in the US, with a liberal shi'a muslim background. The second author is a first-generation Iranian-American from a Jewish background. We are both equally shocked by the current violence against women perpetrated by the government and the morality police in the name of Islam. The brutality goes against Iranian cultural codes of conduct, but has become justified under the current Islamic rubric of authoritarianism veiled as “unity.”

Mahsa Amini’s death was a breaking point for Iranian girls and women, many of whom grew up under the Islamic Republic. In the current uprisings, we are seeing women reject the doctrine and laws creating gender apartheid.

Many Iranians are angry and they desire change.

Women are leading the charge, and this is about much more than the hijab. It is the repercussion of the 1979 revolution, which did not deliver its promises of Islamic justice. Rather than embracing feminist readings of the Quran, the Islamic elite used hidden women as a symbol of their success and enforced a patriarchy at odds with Iranian culture.

The Iranian population is highly educated, spiritual, and sophisticated, with longstanding traditions that celebrate life, democracy, and human rights. Its women are revered for their strength—often referred to as shirzan (pronounced “Sheer Zan”)—which, in its literal translation, means “lion woman.” In practice, it refers to a woman who is courageous, noble, and owns the ground she inhabits—one who fights for justice and will not be silenced.

Through the current uprising, we see the collective force of shirzan—Iranian women, rising up again to fight for justice. One common slogan of the movement reads: “You can’t burn women made of fire.” May we harness such an essence in our support for greater justice in Iran and for all.

Panteá (Pani) Farvid, PhD., is an Associate Professor of Applied Psychology in The Schools of Public Engagement, at The New School, in New York City. She is the Chair of Psychology in the Bachelor's Program for Adults and Transfer Students, and the founder and director of The SexTech Lab. Her research and teaching focuses on the critical psychology of gender and sexuality, psychology for social change/justice, modern prejudice (sexism, racism), and technology and ethics. The current projects she's involved in include: mobile dating during the pandemic, the experiences of young nonbinary folks, black queer mental health, an edited collection on sexual racism and a sole authored book on psychology and heterosexuality.