1. Introduction

Modern understandings of women in Classical Greece have long been dominated by male-authored narratives. These ancient voices—Hesiod, Aristotle, and even the tragic poets—have shaped the widespread belief that women in Greek antiquity held limited social value and were confined to domestic or reproductive roles. The pervasive view, articulated most succinctly by Pericles, is that a woman’s greatest glory lies in being least spoken of. Yet this is not the whole story.

Epigraphic evidence—inscriptions written by, for, or about women—provides a rare but vital window into how Greek women saw themselves. The voices in these texts speak not through male authors but directly from the hands, minds, and lives of the women themselves. They offer another perspective: women as religious agents, economic actors, civic participants, mothers, daughters, and even adversaries. These voices call out from temple dedications, grave stelae, oracle questions, and even magical curse tablets. And they tell us something that ancient male authors often omitted: women believed their lives had meaning, value, and public consequence.

This editorial explores how such inscriptions alter our understanding of women in Classical Greece. Drawing from the findings of my recent EUGESTA article, I argue that women actively shaped their public image and personal legacy. Far from being voiceless, they carved their names—and often their stories—into the stone of Greek public life.

2. Ancient and Modern Views on the Importance of Women in Classical Greece

The conventional view of women in Classical Greece has typically followed the ancient androcentric lens. Aristotle famously likened women to "defective males," and historians from the 19th century onward echoed such dismissals in both tone and content. Earlier classicists such as Becker (1854) and Gomme (1925) have seen Athenian women as politically irrelevant. Indeed, in terms of “importance” women have been ranked alongside slaves. Even as feminist scholarship developed, the paradigm of female exclusion endured, often focusing on women’s domesticity or their symbolic role in male discourse.

Yet, cracks in this monolith have long existed. Sarah Pomeroy’s Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves (1975) challenged traditional historiography by asking and exploring what women actually did—not just what men said about them. Scholars like Joan Blok (1987, 2018) and Eva Cantarella (1987) have since widened the aperture, revealing spaces—especially in religion—where women wielded real influence. Others, such as Dillon (2002) and Eidinow (2007, 2013), have illuminated how women engaged with deities in deeply personal and often public ways.

Despite this progress, most studies still rely heavily on literary sources—texts written by elite men for elite male audiences. The inscriptions left by women themselves, however, offer a vital counterpoint. They do not rely on male representation; they are women’s self-representations. And they reveal something essential: some women in Classical Greece did not accept invisibility. They wanted to be known, remembered, and honoured—not just by their gods and families, but by their communities and posterity.

3. Discussion of the Evidence and New Interpretations

Women as Public Dedicators and Civic Agents

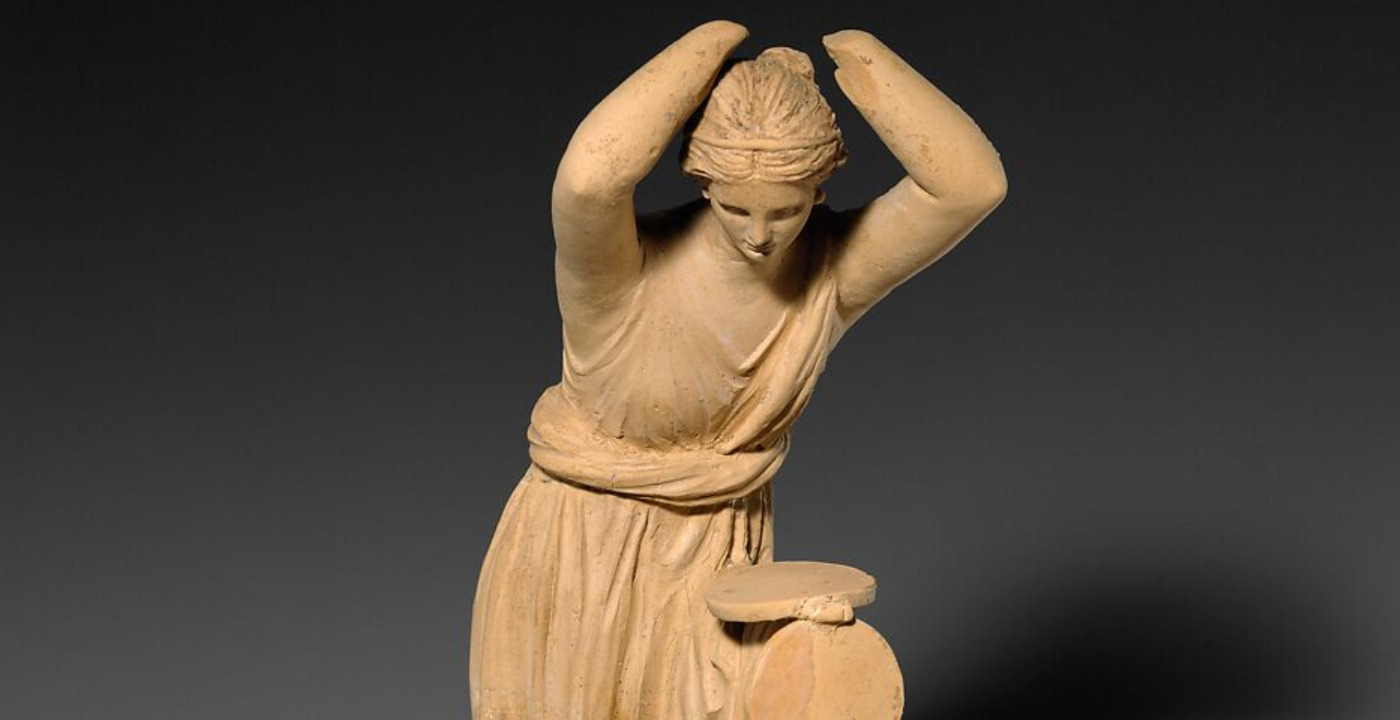

The Athenian Acropolis was not only a site of overt masculine military glory but also a place where women left their mark. Inscriptions on votive offerings—from small vessels to elaborately crafted statues—bear women’s names proudly and often exclusively. Consider Iphidike’s dedication to Athena Polias, which omits any mention of father or husband. Or Smikythe, a washerwoman, who dedicated a tenth of her earnings in gratitude. These inscriptions show that women—rich and poor alike—asserted themselves publicly through religious acts that were also social and political statements.

This self-assertion extended to artistry. Mikythe, for instance, commissioned a sculptor to produce a statue offered to Athena, explicitly thanking the goddess for success as a mother and wage earner. Xenokrateia, who may have founded an entire sanctuary, names herself first in a formal dedication celebrating her education, wealth, and maternal legacy. Even the language of these dedications—sometimes in non-Attic dialect—marks out their individuality and origin.

These women did not seek anonymity despite men’s attempts to render them invisible. On the contrary, they carved their identities into sacred spaces. The names they used, the gods they addressed, and the items they offered constituted acts of self-fashioning, placing themselves within the civic and religious fabric of their community. Their acts show a deep understanding of χάρις (charis)—reciprocal favour between humans and gods—and how this favour could elevate one’s public standing.

Women’s Voices in Memorials and Funerary Texts

In funerary inscriptions, women assert authority over memory itself. Timarete’s epitaph for her son not only honours him but ensures her own name will be remembered. She speaks twice through the monument: once in her voice, and again in her son’s, declaring that she alone erected it. Archippe, another mother, commissions a statue from Praxiteles—perhaps the most renowned sculptor of the Classical age—in her daughter’s name. She inscribes both their names in the public record, asserting matrilineal pride and permanence.

Such inscriptions reframe our understanding of women’s participation in memorialisation. They are not passive subjects but active agents shaping narratives about lineage, death, and honour. They speak not only of loss but of pride, resilience, and enduring connection.

Female Agency in Oracular Inquiries and Curses

Texts from the oracle of Dodona offer a striking glimpse into the inner worlds of women. These lamellae—small lead tablets—record women’s personal appeals to Zeus and Dione. Some ask about health (e.g., Nikokrateia, who wants to know which god to sacrifice to for healing). Others ask about lovers, pregnancies, or the possibility of having children with new partners. These are not abstract or symbolic queries. They are real, urgent, and specific.

They also imply autonomy. Kleunika, for example, asks whether she might bear children with "another man"—an extraordinary revelation of personal agency. Rhazia seeks reconciliation with a man named Teitukos and considers leaving him. Plaurata asks if sex with a specific man will be "good and beneficial." These inquiries are self-authored, individualised, and show women weighing real decisions.

Even more personal and visceral are the curse tablets. Here, women deploy ritual language to achieve social or emotional justice. One unnamed woman curses Aristokydes and all women who might win his love. In another, the infamous "Thetima curse" from Pella, [Phil]a asks that her rival Thetima die a miserable death so that she alone may marry Dionysophon. These are not polite prayers. They are forceful, strategic actions aimed at shaping the course of relationships and futures.

And they are fundamentally personal. Like the oracles, they show women as actors—not victims—in their own stories. They expose rivalries, desires, betrayals, and hopes. They are emotional documents, but also political ones: each curse reflects a claim to legitimacy, recognition, and love.

4. Significance of Findings and Conclusions

The inscriptions reviewed here provide a compelling new angle on the lives of women in Classical Greece. While male authors often defined women by silence or subservience, women’s own inscriptions tell a different story: one of religious significance, economic agency, maternal pride, social participation, and personal ambition.

These women claimed space for themselves—in sanctuaries, cemeteries, and sacred precincts. They spoke in prose and in verse. They named themselves, sometimes first. They honoured gods, loved ones, and even themselves. They praised their own virtues and professional skills. They memorialised their dead, shaped their family’s legacy, and made offerings that served both divine and civic ends.

Far from confirming their insignificance, these texts argue for their presence. Women in Classical Greece may have been barred from political office and assembly, but many still acted as political agents. Through dedications and other public texts, they built a form of fame (κλέος, kleos) in defiance of Pericles’ instruction to remain invisible. As their words were read aloud—by priests, by fellow citizens, by family members—their voices were carried into the public soundscape of the polis.

These are not outlier cases. The evidence is geographically widespread—Athens, Dodona, Posidonia, Pella—and chronologically consistent. They come from elite women and working women alike. They cross multiple genres and styles—dedications, oracles, curses—and yet, the motive is the same: to be seen, heard, valued, and remembered.

All of this changes how we should write women's history. It urges us to centre female perspectives when we can, to attend to inscriptions, lamellae, and material traces as valid historical voices. It means confronting the biases of ancient male writers and correcting the distortions of later historiography. As feminist scholarship continues to reinterpret ancient sources, these inscriptions should form part of a new canon—one defined not by absence, but by presence.

Women in Classical Greece were not just daughters or wives or mothers. They were donors, dedicators, decision-makers, and diviners of fate. Their lives mattered—to themselves, to their gods, and to us. Their words, carved in stone or etched on lead, still speak. It is time we listened.

References

All scholarship cited in this editorial is included in the original article ‘ ‘Now I still honour you ... the first honours are yours’: Women’s public and private epigraphic texts from Classical Greece, ‘ Eugesta [Online], 14 | 2024, Online since 17 décembre 2024. DOI : 10.54563/eugesta.1583 For a full bibliography, please refer to that publication.

Associate Professor Ian Plant is a member of the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University.