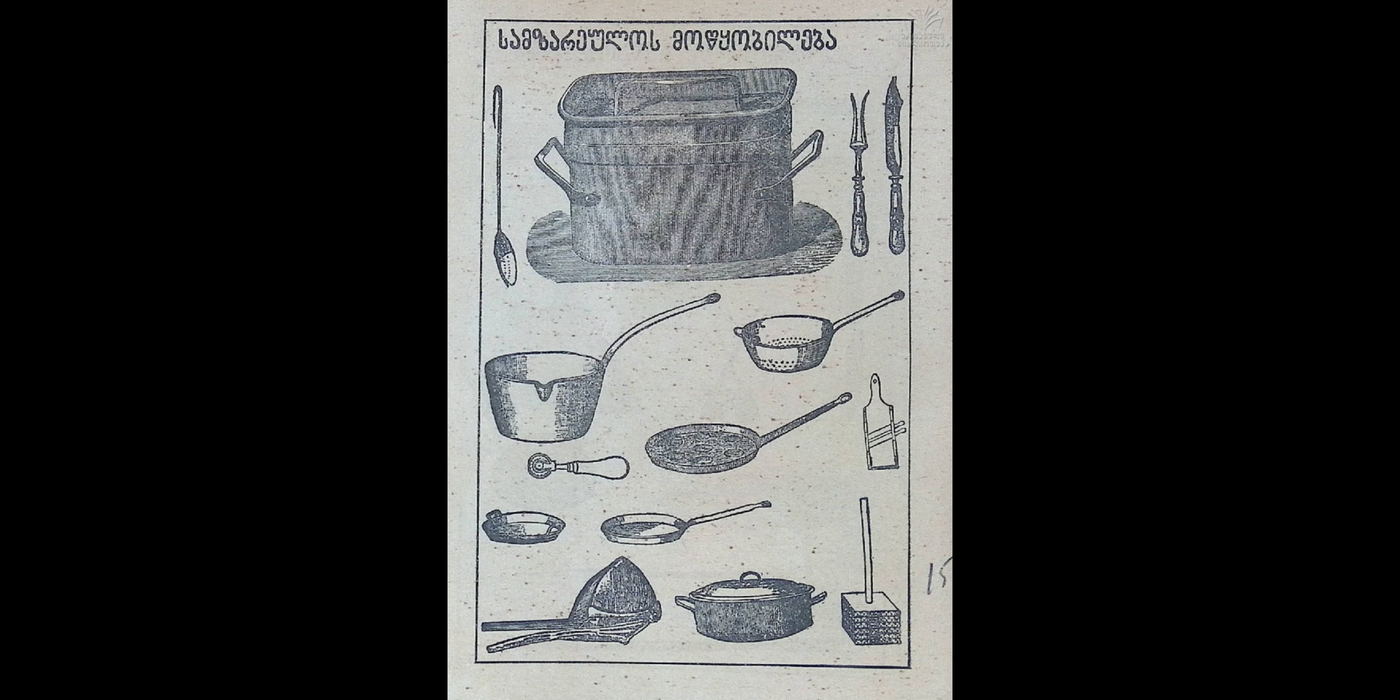

Georgia’s first feminist was the princess and author Barbare Jorjadze. Born in 1833, when the country was still part of the Russian Empire, Jorjadze is remembered for her cookbook Georgian Cuisine and Tried Housekeeping Notes, an esteemed household item with dishes that have survived two world wars and the rise and fall of Tsarist and Soviet empires. But Jorjadze, though a devoted mother of three, extended her professional work far beyond the realm of domesticity.

Home-schooled from a young age, Jorjadze was taught to read and write by her peasant nanny, Dilavardisa; later in her life, she called attention to this in her writings about women’s roles and education in Georgian society. Jorjadze was the daughter of Prince Davit Eristavi. At twelve years old, she was married to Zakaria Jorjadze, a military officer who was expelled from Saint Petersburg Military Academy for physical assault. In 1985, for the newspaper Iveria, Georgian writer Mariam Demuria recalled Jorjadze’s description of the wedding:

At that time, women were forced to get married at a very young age and I was so young that when a wedding ceremony was held in the church, I thought we were playing something. When the priest was performing the marriage ceremony, a bat flew into the church. When I saw it, I told the priest: Please, I beg you, keep silent. I think my nightingale has just flown in and I want to catch it (Demuria 1895).

Arranged marriages between adult men and young girls were common in 19th century Georgia. Jorjadze’s simple but emotional account of her wedding illuminates women’s lack of agency in this era.

In 1858, Jorjadze began her writing career. She rarely mentioned her husband in her writing, but she had a close relationship with her brother, Rapiel Eristavi, a historian, poet, and member of the Georgian literati circle. Jorjadze was the first woman to gain entry into this circle of men, and she did so by publishing her writing in the widely-read literary publication Tsiskari.

With this, she established her position as a poet, playwright, and essayist. Unsurprisingly, Jorjadze encountered public criticism, but she continued writing, collaborating with the newspapers Iveria, Kvali, Droeba, and Jejili. In her essays and letters, she was concerned with the conditions and rights of Georgian women; she blamed much of their oppression on women's lack of access to education.

In 1893, Jorjadze published a letter entitled “A Few Words to the Attention of Young Men,” which, in many ways, was a manifesto for Georgian feminism. She began by highlighting the pervasive mockery of women throughout history:

Since the very beginning, every man has been mocking women… From childhood, we are told: ‘Since you were born as a woman, this should be the rule for you. Keep your voice low, be quiet, look at nobody, go nowhere, shut your ears and eyes, and just sit there…Education and learning is not your concern’…The men even neglected the work of the women in the family…

Despite the restrictions on women’s autonomy, Jorjadze never believed men suppressed women’s minds and talents, writing in the same letter:

Women [have] been the custodians of knowledge and champions of literacy when men held to their weapons and fought to defend the homeland.

By noting that women were custodians of knowledge while men were engaged in warfare, Jorjadze challenged the traditional glorification of men in battle and emphasized the overlooked contributions of women. She criticized the fiction perpetuated by men: when men claimed, “You [women] do not have intelligence, you don’t have heart or feeling, you do not understand, you are deaf and blind, you can’t see, you are merciless, treacherous…” Jorjadze refuted them in return.

What hasn’t man called to his worshiping being, which is a mother, sister, wife, and daughter. As if a woman and a man were not created by the same power and nature.

Like other 19th century European and American women, Jorjadze insisted that men perceive and radically change the social structures limiting women. In a final call to action in her published letter, she urged men to:

Abandon pride and envy and let your sisters have equal access to education and tutoring and the new generation of women will spare no labor and energy to contribute their share to progress.

Barbare Jorjadze was a culinary marvel, but her career extended far beyond the recipes she created that still live in the kitchens of Georgian households today. The New Historia calls attention to women like Barbare Jorjadze whose thoughts and contributions alter our understanding of the past when fully seen and remembered.

***

This is part two in a series of editorials dedicated to celebrating the resilience of Georgian women. The histories of women challenging societal norms and advocating for gender equality have often been obscured by misogynistic veils. This series aims to shed light on the lives of five extraordinary Georgian women spanning the centuries, each contributing uniquely to the ongoing narrative of feminism. From the Middle Ages and the reign of Queen Tamar to the early 20th century, featuring the feminist pioneers Maro Makashvili, Kato Mikeladze, Ekaterine Gabashvili, and Barbare Jorjadze, these women carved unique paths in Georgia, challenging the limitations placed upon them. By weaving together the stories of these remarkable figures, this series seeks to explore the diverse dimensions of Georgian feminism and unveil the collective strength that transcends temporal and societal boundaries.

These women, with their fighting spirit, can become a source of inspiration for many people, if only they are known. Their ideas provide solid ground for the empowerment of women, which is no less important today than it was hundreds of years ago. Everyone should be familiar with the heroes who are lost to the labyrinths of history, who fought against stereotypes and misogyny—stereotypes that, for some reason, are passed down like an incurable disease.

Tata Jagiashvili is a graduate student at The New School in New York City, pursuing a master's degree in Media Management. She is a Public Engagement Fellow with The New Historia. Tata holds a bachelor's degree in Social Sciences from the Free University of Tbilisi in Georgia.