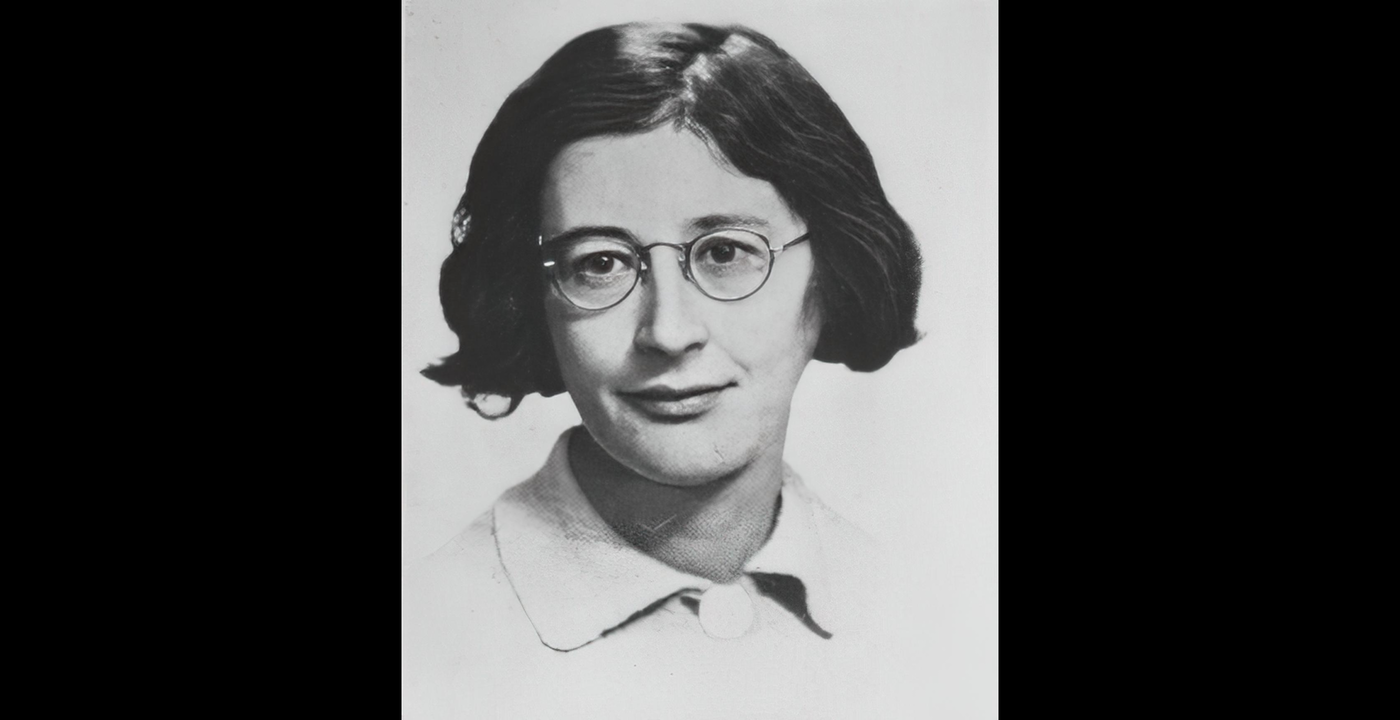

Simone Weil is a salvific figure, a philosopher whose passions and ideas become guiding values by which to live. I encountered her for the first time as a directionless sixteen year old in a highschool philosophy course, and I quickly joined the ranks of Susan Sontag, Patti Smith, Albert Camus, and many more, in my love of her political philosophy and Christian mysticism. As I sifted through the world of Weil, I discovered most of her publications–almost all published posthumously–were political writings, but it was her spiritual work, which she only came to later in her life, that stuck with me. I found her forceful, practical, and cryptic prose served to capture the divine with an exacting clarity that made obvious a fuller, more empathetic way of living.

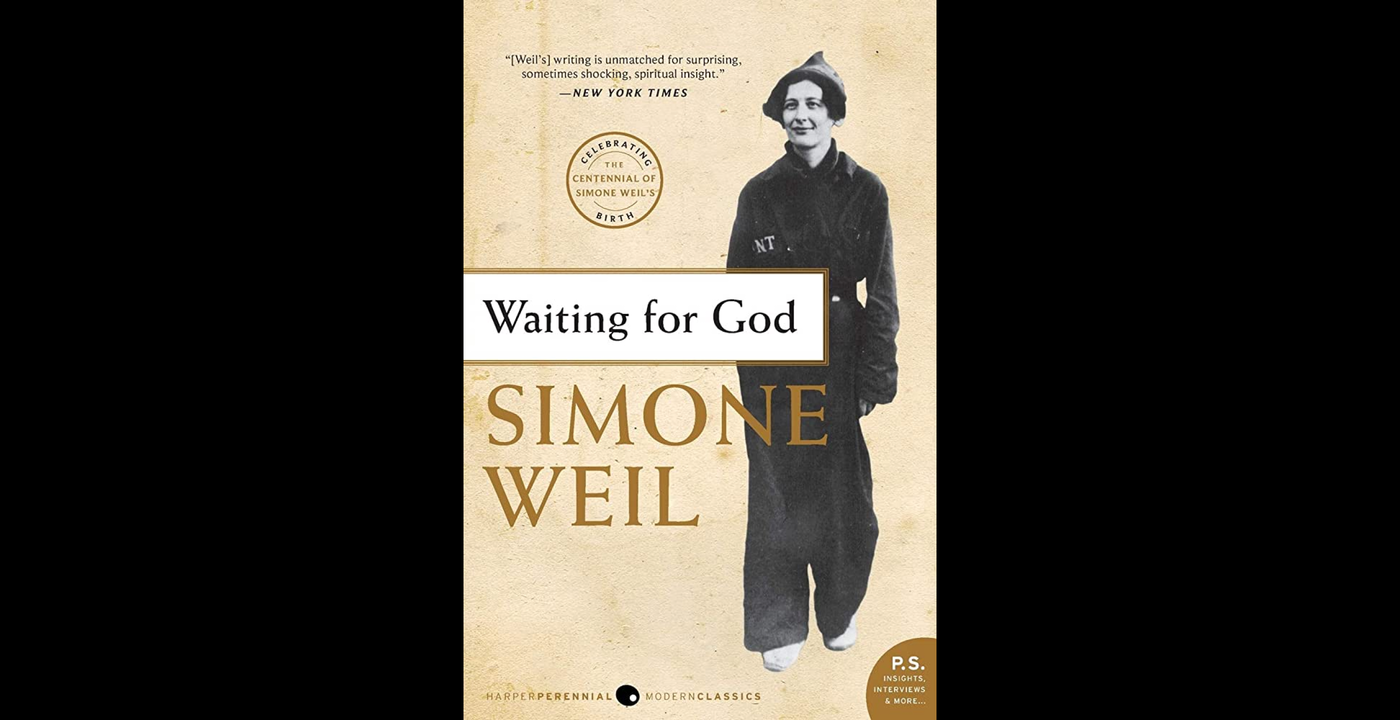

Weil’s theology is collected in an elegant volume, less than two-hundred and fifty pages in length, entitled Waiting for God. Chief among the concepts she explores here is the notion of ‘attention.’ In the essay, “The Right Use of School Studies With a View to the Love of God,” Weil writes:

The love of our neighbour [...] is made of [attention]. Those who are unhappy have no need for anything in this world but people capable of giving them their attention. The capacity to give one’s attention to a sufferer is a very rare and difficult thing, it is almost a miracle; it is a miracle.

Weil argues that loving one’s neighbor is asking: ‘what are you going through?’

This must be asked with full attention, meaning the asker must suspend thought, “leaving [their mind] detached, empty, and ready to be penetrated by the object.” Attention, best used when directed towards the sufferer so that she may be better understood, is surrendering the imagination’s sense-making faculty. In other words, as I write in my article To Fix The Image in Attention: “It is pure perception, untainted by the explanation. [...] By engaging in attention, we perceive what is as it is before jumping to conclusions about what we are perceiving.” When this type of Weilian attention is directed at other people, it helps us resist reduction, stereotyping, and monoliths. Attention is seeing without judging or categorizing.

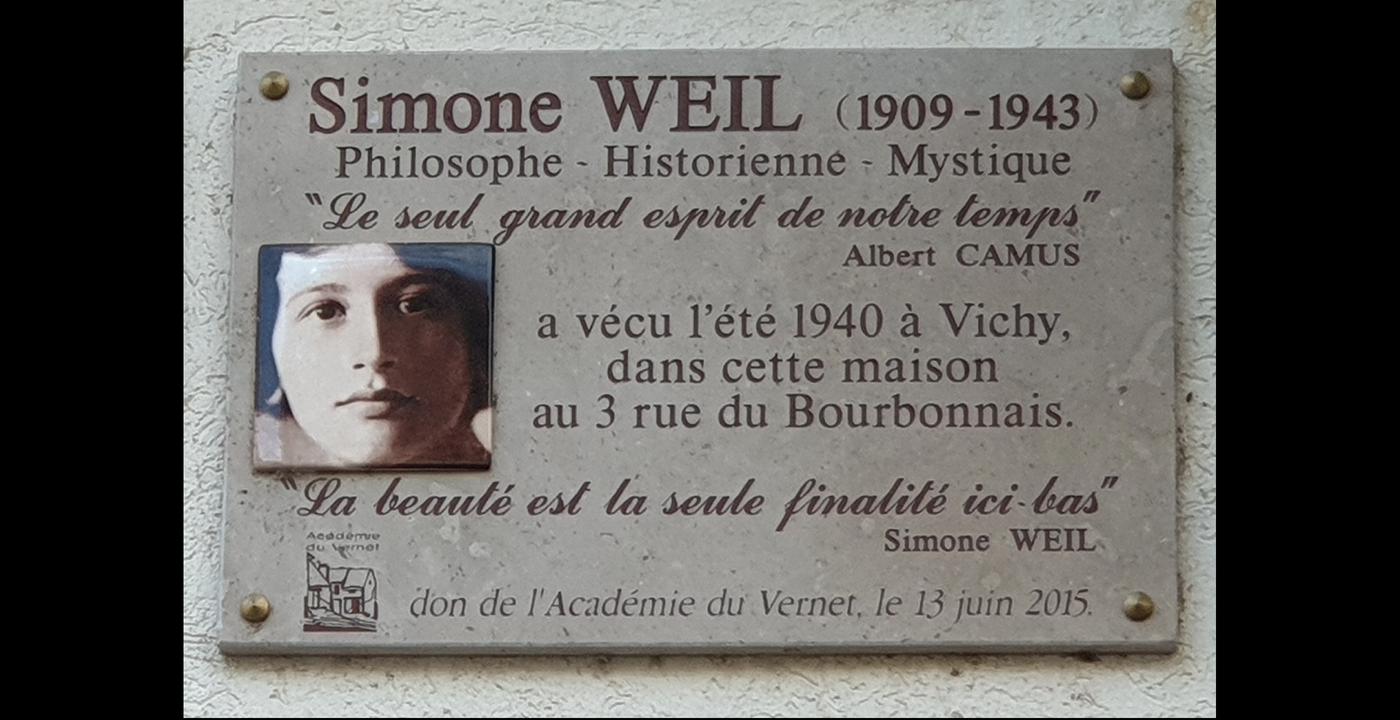

In light of this concept, it is a wonder that Weil’s commentators have failed to do the one thing that Weil wanted us to do in our spiritual lives: see each other, and Weil herself, complexly. Published largely by her father, Bernard Weil, and Albert Camus after her death, Weil’s philosophy and story is one composed of the male gaze, what Camus and Bernard Weil thought she should be, not who Weil thought she was. Some little-known facts about Weil: she was ethnically Jewish, but her family, atheistic mathematicians, did not practice; she suffered from internalized anti-Semitism, which led her to make scathing comments about the Old Testament. In fact, when a law passed in Vichy’s France prohibiting the employment of Jewish people in schools, Weil railed at the idea that she might be considered Jewish at all. This contradiction — of a Jewish woman denying her ethnic roots, of a woman who preached care for the sufferer and yet did not extend that same care to the plight of her own people — is often erased from the cultural understanding of Weil because it is messy. Her work is written off as wholesale because we want heroes and heroines ideologically tidy and uncomplicated.

Thinkers, particularly women philosophers, are thrust into a plane of moral superiority. From there, they are worshiped as beacons of ideological purity. When some hypocrisy within them is inevitably revealed, they become heretics to their cause. To Weil, these reactions are merely a symptom of attachment: a failure to see the things of this world as mere illusions distracting us from the work of ‘decreation.’ Weil’s decreation is the process of unselfing, of losing the ego so that God might stand in its place. Decreation provides a pathway to fully attending to the world and particularly those we share it with, those living and those gone, beyond ideological lines and boxes.

If proper attention is paid to our heroes and famous thinkers, we would see them as complex individuals, whose tensions and flaws do not detract from their work but add to our understanding of it.

Weil did not believe attention was truly possible except in rare circumstances, and she held herself to the highest degree of scrutiny when it came to her ability to perform the act — yet she still attempted. As must everyone in seeing our heroes — particularly our female heroes — complexly.

Nellianne Bateman will begin her MA in Liberal Studies at The New School for Social Research at the end of August. When not pouring over mysticism (Simone Weil), political theory (Hannah Arendt), or feminist existentialism (Simone de Beauvoir), she can be found at her local café, reading, sketching, or writing.