Mary Ann Parker was the first European woman to publish a travel memoir of her voyage and visit to New South Wales in 1791 and 1792. When the British founded the penal colony at Port Jackson in February 1788, they declared the Colony of New South Wales on the continent now known as Australia. Her book, A Voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war (1795), included vivid descriptions of the voyage and of her time on shore in Tenerife, the Cape of Good Hope, and Port Jackson. Parker may have kept a detailed journal of her travels to New South Wales, which were undertaken with her husband, the British Royal Navy Captain John Parker of HMS Gorgon.

Parker was already an experienced European traveller before her voyage to New South Wales. In Tenerife in 1791, she was a Spanish language interpreter, conversing readily with everyone from the Governor’s social circle to guides and servants. In one of few direct references to memories of her previous travels with her parents, Parker wrote that the view from where she stayed in the Cape of Good Hope reminded her of Livorno or Leghorn, where a road around the quarantined lazaretto led up out of the port town and climbed into the Montenero hills. The port of Livorno was likely where she had arrived by sea from Spain twelve years earlier.

During the outward voyage, Parker shared the company of other travellers with appointments in New South Wales. These included the Lieutenant Governor of Norfolk Island, Philip Gidley King; the botanist David Burton; and the surveyor Charles Grimes. Parker also enjoyed the company of Anna Josepha King, who was travelling with her husband. Both women were in their mid-twenties. Shortly after embarking on HMS Gorgon, Anna Josepha King must have realised that she was pregnant with her first child and may have welcomed Parker’s companionship. John and Mary Ann Parker’s fourth child was conceived while they were in New South Wales, where Parker socialised with Anna Josepha until the Kings left for Norfolk Island.

Parker enjoyed how she and her husband were entertained as guests in New South Wales. They were included in Governor Arthur Phillips’ social circle. She ate local meat and seafood, from kangaroo to oysters, and she appreciated the generosity of official residents, who occasionally made her gifts of eggs and other produce.

Parker was the first person to write about New South Wales as a European visitor who had not sailed with the First Fleet. She admired the buildings and street plan at Parramatta and the cultivated land at Rose Hill. By the time A Voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war was written in 1795, some of those who returned to Britain in 1792 had published accounts of the penal colony’s first four years.

While travelling, Parker largely ignored the presence of some people, or described them in a distanced way. During her stay in New South Wales, Parker said very little about the transportees, and expressed no opinion regarding the policy of transportation. At the Cape of Good Hope, Parker accepted that those waiting on her table were enslaved Africans, not employed servants. While visiting Sydney Cove, Parker described the landscape and topography, and she very briefly noted the presence of the aboriginal people–the Eora–and their homes and canoes.

On the homeward voyage, HMS Gorgon carried marines and their families returning from New South Wales. The return voyage was difficult. Twelve children died, one in four of those who embarked. In the third trimester of her pregnancy, with diminishing supplies of fresh fruit and vegetables onboard, Parker’s account of the homeward voyage after leaving the Cape was flat and terse. At Portsmouth, Parker was one of the first to disembark. After staying one night in an inn she travelled by coach to London, where her son was born.

Three years after her return, Parker wrote her book to raise funds for her family, and to commemorate her late husband. Parker included Captain John Parker’s proposals for the development of a whale fishery, about which he had discussions in New South Wales. She also quoted her husband’s criticisms of conditions onboard the transport ships, citing the damaging impact of transportation on the health of transportees.

While in New South Wales, Parker had not focused on the impact the Eora people faced because of the British settlements. A year after she arrived home, the Atlantic transport reached Falmouth in Cornwall on May 19, 1793. Stepping ashore in Britain for the first time, Woollarawarre Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne transferred to a coach for their onward journey to London with the returning former Governor Arthur Phillips and surgeon Richard Alley. Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne were the first recorded Eora people to travel to Britain. A year later, Yemmerrawanne died. Bennelong later called on Parker in London. In writing about his visit, Parker belatedly acknowledged that she and Bennelong shared a common humanity, and might each experience personal loss and grief.

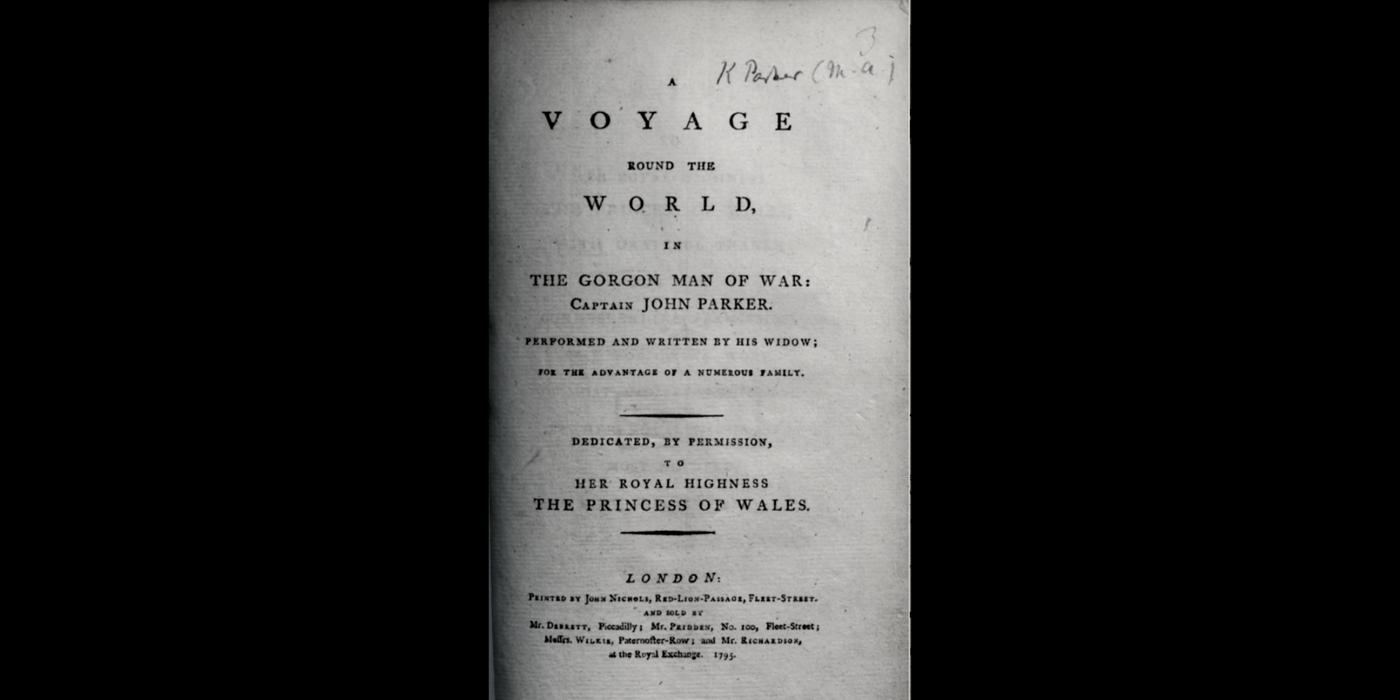

Mary Ann Parker obtained a nationwide list of subscribers ahead of her book’s publication and dedicated the text to the Princess of Wales. These factors indicated the book would generate significant interest. The subscribers included extended family, friends, and commercial, as well as naval and literary contacts. The list included some well known women. The educator and philanthropist Hannah More chipped in her support, as did Frances Boscawen, the salon hostess and bluestocking, who was the widow of an Admiral. London literary subscribers included the editor of the Gentleman’s Magazine, John Nichols. And the founding editors of the British Critic, William Beloe and Reverend Robert Nares. Half a century later, a notice of Parker’s death in 1848 appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine, which was by then edited by John Bowyer Nichols, whose father, John Nichols, had printed and appreciatively reviewed A voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war (1795).

Dr Charlotte MacKenzie is an independent researcher and former UK university senior lecturer in history with many publications since 1983.