At thirty-two, in the wake of her mother’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, writer and editor Joanna Biggs realized she wanted to change the trajectory of her life. Before that moment, she saw a defined path, and it led to a suburban home and a child with her then-husband. Instead, Biggs decided to take a different turn, divorcing her husband and uprooting her stable life.

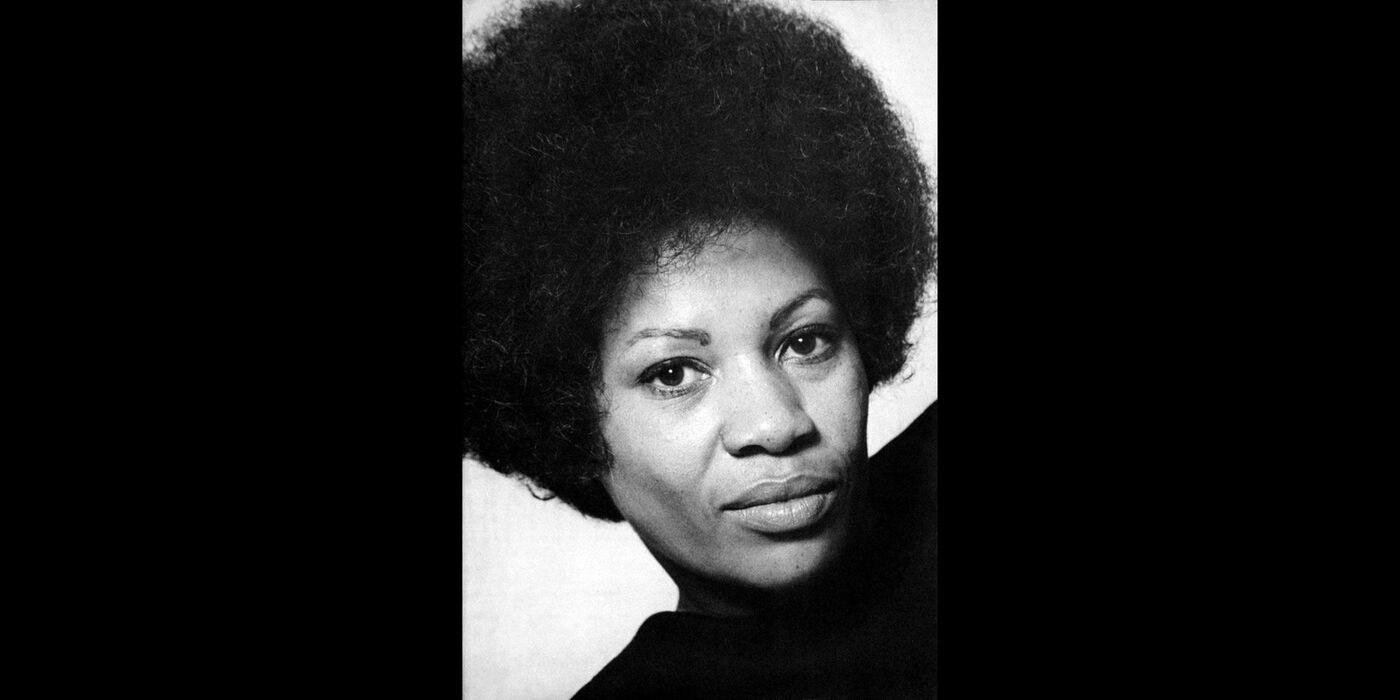

Freed from constraints, Biggs turned to eight writers–Mary Wollstonecraft, George Eliot, Zora Neale Hurston, Virginia Woolf, Simone de Beauvoir, Sylvia Plath, Toni Morrison, and Elena Ferrante–searching for proof that fulfillment, intellectual and otherwise, can be found in the untethered state of her new future. A writer and thinker herself, Biggs’s search resulted in A Life of One’s Own: Nine Women Writers Begin Again. This highly anticipated book celebrates women writers who made and remade themselves by flouting the female ideals of their times in favor of intellectual freedom. In this combination of memoir, criticism, and biography, Biggs closely reads the writing of the eight writers mentioned above, examining how they were influenced by the legacies of women who came before them and how they contributed to those who came after.

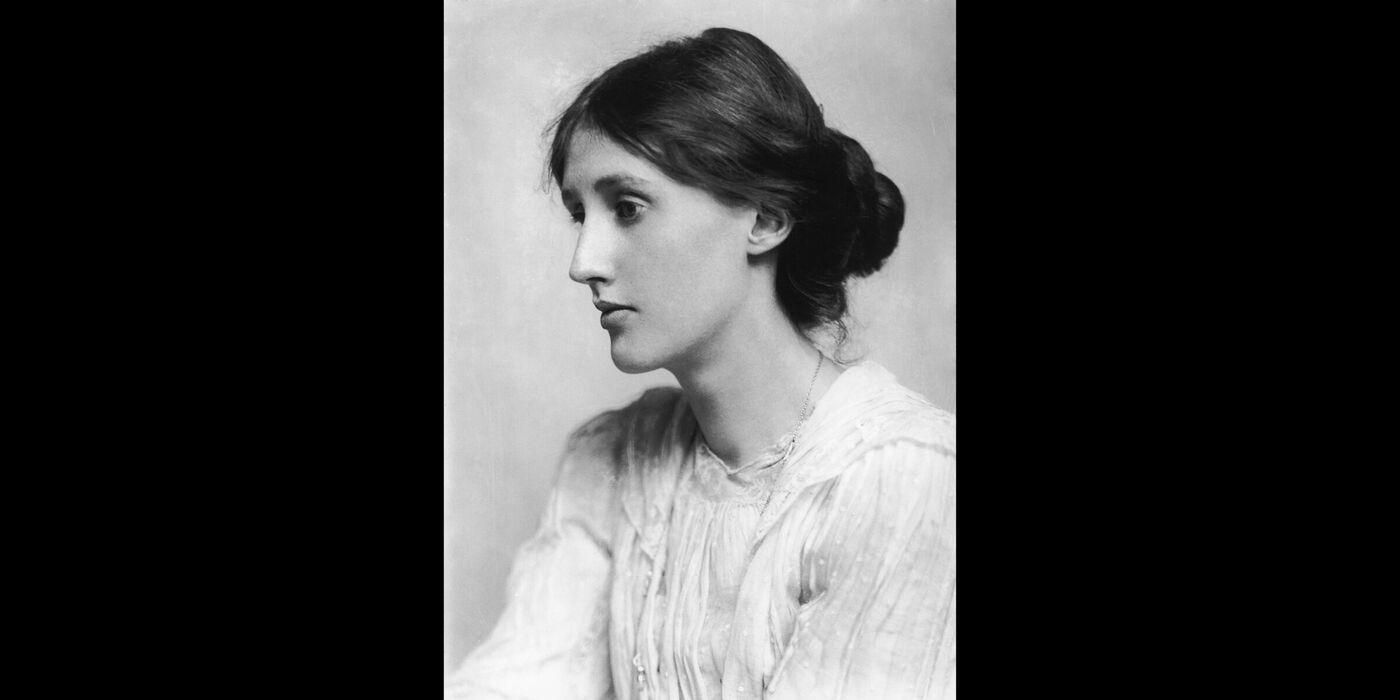

Biggs herself is the ninth writer referenced in the title. She weaves the story of her life and the tumult of her post-divorce time period into the stories of these writers. In a Virginia Woolf-esque style, Biggs engages in a form of life writing, what the author of Romantic Women's Life Writing: Reputation and Afterlife, Susan Civale, describes as, “a mixture of literary criticism, biographical sketch and personal response.” Biggs begins A Life of One’s Own in this way, recalling her encounters with Mary Wollstonecraft, to whose grave she finds herself almost preternaturally drawn.

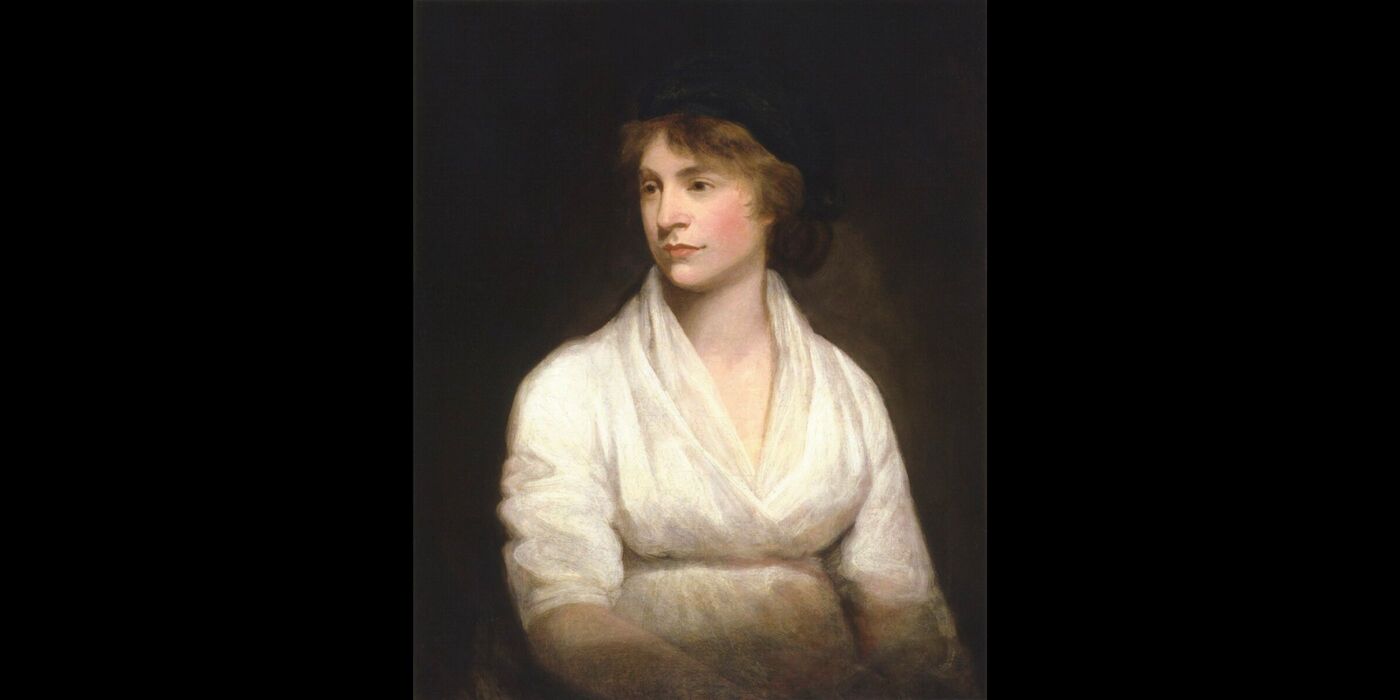

Biggs is primarily concerned with the intensity and vigor with which Wollstonecraft lived and loved. Born in 1757 and best known for her 1792 Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft was unconventional. She moved to Revolutionary France and had two failed love affairs—the first with Swiss painter Henry Fuseli and the second with American speculator Gilbert Imlay. Painfully jilted by Imlay, whom she loved deeply, Wollstonecraft sailed to Scandinavia hoping to track down his lost silver. This journey resulted in her impassioned Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796), which were later collected, published, and beloved by readers.

These letters were Wollstonecraft’s most popular texts among contemporaries and became a tool for her to shape her persona and public image, allowing her to omit much of her tumultuous story, with its failed loves and suicide attempts. Wollstonecraft intentionally camouflaged the details of her life in which the modern reader, including Biggs, finds so much resonance. This kind of cultivation, Civale writes, was of the utmost importance for women writers whose literary works were an entrance into the public arena, whose reputations influenced their earning potential, and whose morality was judged by harsh standards.

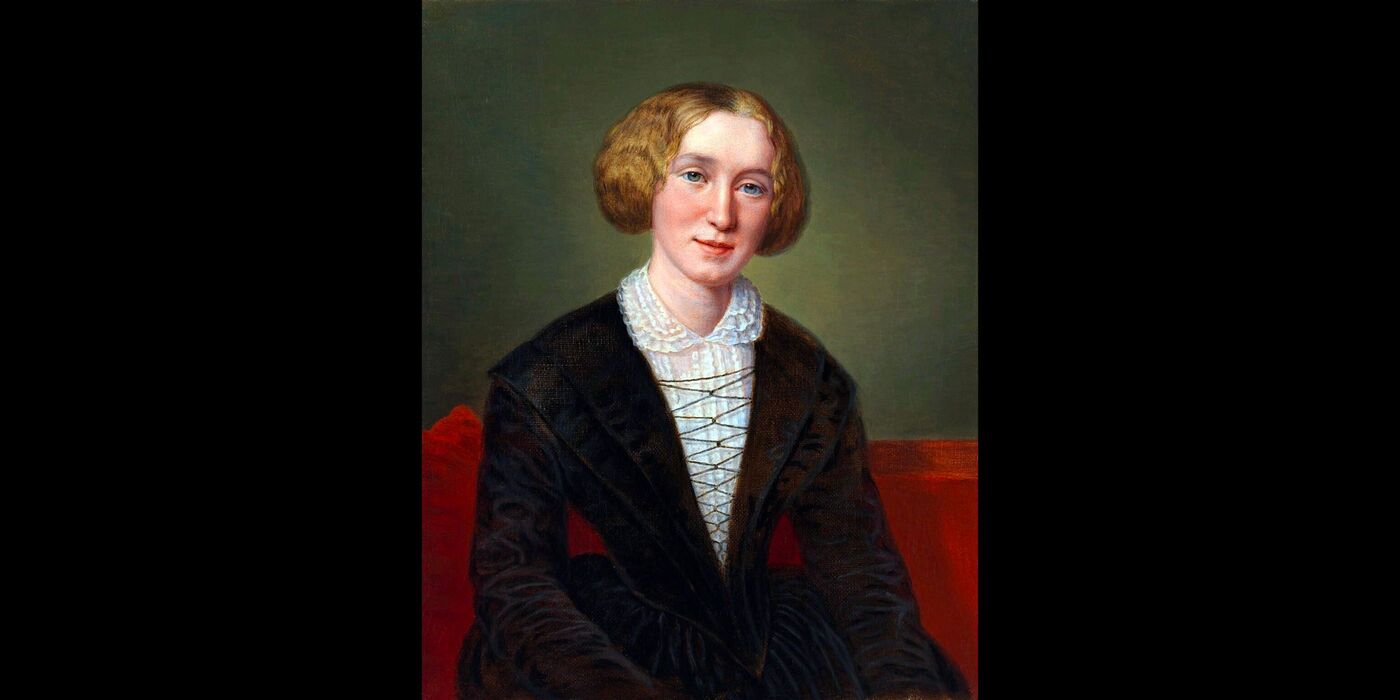

Still, Wollstonecraft—brave, intrepid, and able to start again and again—serves as an anchor for Biggs as she finds herself adrift and reforming her life in the wake of loss. Interestingly, Wollstonecraft was also an anchor for George Eliot (1819-1880), author of Middlemarch and the pseudonym for Marian Evans. Early in her writing career, Eliot quoted Wollstonecraft in an essay, and she does so again in her letters later in her life, writing about Wollstonecraft’s suicide attempt and how in that dark period, she came to see the light that she might find ahead.

The moments of connection between writers across eras in Biggs’s book are some of the most moving and interesting aspects of her writing. She examines Eliot and Woolf’s reading of Wollstonecraft, how Woolf and Simone de Beauvoir revere Eliot, how Toni Morrison brings up Zora Neale Hurston as “...casually and habitually as if she were always there,” and more. Biggs documents how they all influenced and paved paths for one another. At one point, Woolf even hung a letter of Elliot’s in her study to remind herself that Eliot did not begin publishing until later in her life. Eliot may not have opened the door for Woolf, but she showed her that the door existed.

The writers in A Life of One’s Own hold similar experiences. Many hit their intellectual strides in their mid to late thirties or forties, publishing later in their lives, and many also experienced great sadness, with multiple attempts of and deaths by suicide, struggles with mental illness and depression, and experiences with other forms of loss. Despite the immense sadness they each experienced, the overarching theme of Bigg’s book is one of possibility: the possibility of living a different kind of life, in finding fellowship in the writing and details of another woman’s history.

Biggs shows how Mary Wollstonecraft, George Eliot, Zora Neale Hurston, Virginia Woolf, Simone de Beauvoir, Sylvia Plath, Toni Morrison, and Elena Ferrante helped provide models and contexts for many different kinds of life, expanding the boundaries of what Biggs thought possible. It is in this lineage of hope and boundary pushing thought and art that Biggs finds the heart of her book, linking nine women together across time and place.

Sam Paul is a writer based in Brooklyn. She is a graduate of the New School and NYU. She is a frequent contributor to the Feminist Book Club. Her writing has also appeared or is forthcoming in various print and online publications including Fourth Genre, Gravel, and Refinery29.