Christine de Pizan (1365-1430) was an Italian and French Medieval/Renaissance writer who is known for authoring some of the earliest pieces of feminist literature. This is what Christine de Pizan means to scholar Inès Villela-Petit.

A comforting voice from afar. What does Christine de Pizan mean to me?

My first encounter with the medieval writer Christine de Pizan was incidental. The American Art Historian Millard Meiss devoted a chapter of his monumental French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry: The Limbourgs and their Contemporaries to the iconography of Christine’s manuscripts. It was a fascinating subject to which I promised not to devote myself! Why was that? Because I thought that it was already well studied under the authority of Meiss and Sandra Hindman’s Christine de Pizan's “Epistre Othea”: Painting and Politics at the Court of Charles VI, and I was considering devoting myself instead to the many manuscripts and illuminators that remained to be rediscovered. However, Christine had not said her last word. I soon realized, great works of art and literature never cease to speak to us, and inexhaustibility is a quality of genius.

One fine day, during a symposium, I met Gilbert Ouy, a great specialist in French pre-humanism and christiniennes studies, already retired. He had studied the manuscripts of a contemporary of Christine, the iconographer Jean Lebègue, and so did I, so I sent him a copy of my thesis. He appreciated my work and immediately asked me to join the small team he was forming with Christine Reno, from Vassar College, for the study of the original manuscripts of Christine de Pizan. They were looking for an art historian to deal with the illuminations and the marginal decoration. I accepted the challenge.

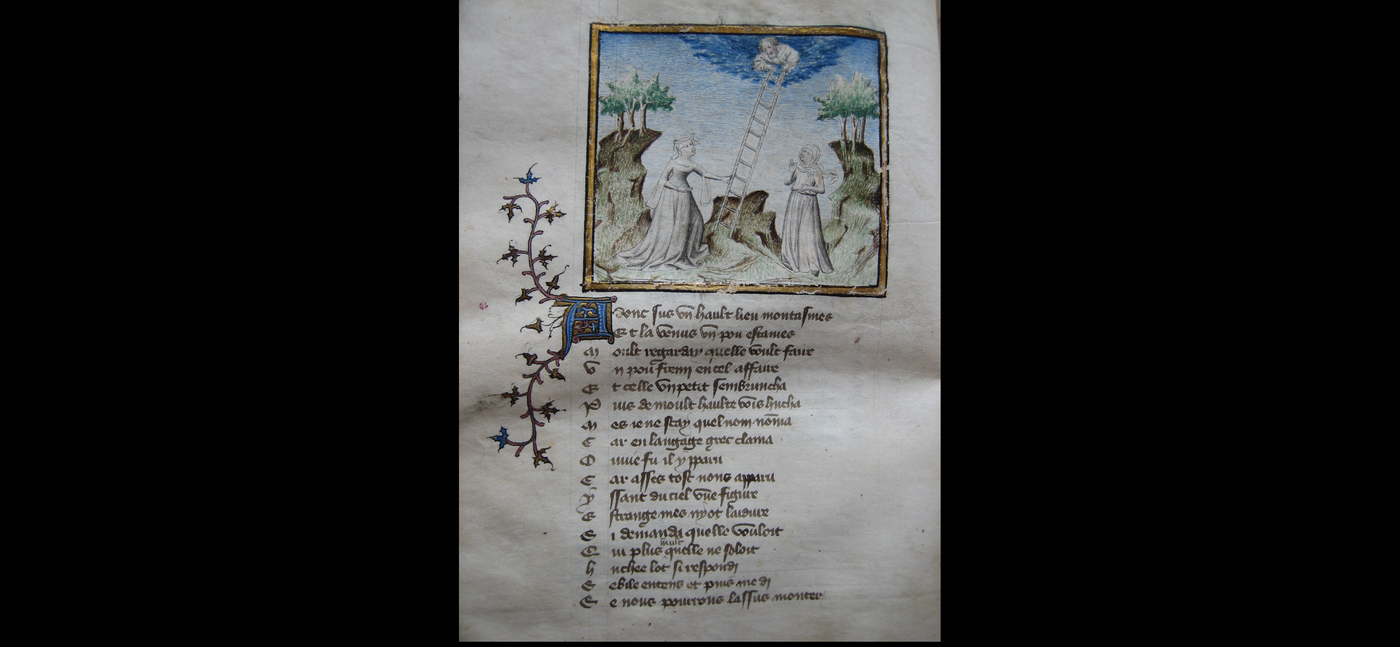

A challenge it was indeed, because Christine de Pizan had not only made herself a prolific creator of illustrations for her texts but the illuminators she called upon were more numerous than those whom Meiss had identified. As for the painted borders and the ornate initials, it was an almost virgin field which required new methods. Studying Christine's images and her illuminators at work involved delving into her texts. And that's how I became familiar with her thought, through text and image.

I became familiar with Christine’s voice, the voice of a lady in blue from the Middle Ages who compared herself to a small bell ringing loudly and had the foreknowledge that she would be read in the centuries to come.

Years later, with the support of our colleagues from Louvain-la-Neuve in Belgium, the fruit of this research was published in a voluminous Album Christine de Pizan. This attracted the attention of the best French specialist in medieval illumination, François Avril, and of the Léopold Delisle committee, which supports studies in a new academic discipline: the history of books. The committee commissioned me in Spring 2018 to write a new book on Christine’s manuscripts to be published by the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Again, when I thought I had said it all, I plunged back into the multi-faceted work of Christine with the happiness of further deepening an acquaintance, a relationship, a kind of subtle friendship with her that transcends the centuries. The more I know Christine de Pizan, the more I admire her intelligence and her relevance.

The études christiniennes happen to be at the crossroads of many contemporary issues. Coming from a matriarchal family, which has favored the intellectual studies of its daughters, I found myself sensitized to questions of which I previously had no concrete experience, starting with the cause of women and the difficulties for a woman to gain respect. Although I have become an authority in my field, I began to experience the difficulties Christine and women throughout history have faced on a daily basis; my professional career as a museum curator stagnated and the worrying signals that my privileged background had always protected me from began to multiply.

As feminism makes its way into the discourse of French elites, the bureaucracy remains a macho power structure that systematically downplays violence against women.

What is the point of bolstering the procedures against aggression and misogynistic behavior if they are not applied?

In September 2018, while working in the calm reading room of the Bibliothèque Richelieu in Paris, I had papers thrown in my face and the words “put them in your a…!” shouted at me. And, in the end, I was reproached for asking for a written apology, a precedent that allowed such actions to occur again and again. It is a strange feeling to experience what should not be, and it is unpleasant to discover the solemn pledges and rules are just words in the wind when social indifference prevails. The violent words of the humanist Jean de Montreuil against Christine de Pizan came back to me. It was said in Latin, in literary form, but nonetheless an insult: “…this woman called Christine, who now delivers her writings to the public. Though not altogether lacking in wit – so far as a woman can have – I seemed to hear the Greek prostitute Leontia, who, as Cicero reminds us, dared to write against the great philosopher Theophrastus.”

I started to get depressed amid this toxic atmosphere. In the evenings, I tried to focus on my writing of L’Atelier de Christine de Pizan; Christine was a sister, a model of resilience.

She had been through such things and managed to get rid of them by dint of perseverance and spirit.

So many times she had herself been represented alone in her study, in the company of books and sometimes a small white dog. So I was writing about her, in a mirrored state, with the editions of her books around me. I still had with me Shalimar, my beloved Birman cat. Christine was there, a benevolent presence-absence. At times I felt like I was looking over her shoulder and seeing her write. At times, her life experience seemed so close to mine: the search for justice in Court, the lawyers who ruin you, the sad feelings, the circle of friends which is reduced, the fear of falling and finding oneself without resources.

But the worst was yet to come. The harassment didn’t stop. It crescendoed. I was reproached for having protested the misogyny I was experiencing, for having made the affair public, for undermining the honor of the Library! This last reproach came as I handed in my final typescript. The publication coincided with my suspension from my work without pay. What honor is this? In the time of Christine de Pizan, honor had meaning among the servants of the state, many of whom were valiant knights, founders of chivalric orders for the defense of ladies and her supporters against the contempt of a Montreuil. It was a long time ago.